On the evening of June 15, hundreds of Indian and Chinese troops laid aside their arms and took on each other in a brawl on the ridge of a mountain in Ladakh, a desolate high-altitude plateau in the northeast Kashmir. The clashes, in which clubs and stones were used, left a bloody trail of dead and wounded soldiers on a frontier that had not seen such violence in the last 45 years. And as India buried 20 slain soldiers from the fight, it began to contend with the high political cost of its ill-thought-out actions in the Himalayan region.

India's unilateral action to revoke the special status of the disputed territory of Kashmir in August 2019 was intended, in the grand strategy of its Hindu-nationalist Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to usher in "peace and development" in the restive state.

What has resulted from it instead is a never-before-seen military confrontation between three nuclear powers - China, India and Pakistan - and the terrifying prospect of a whole region descending into the hellish vortex of war, mass suffering and widespread economic chaos.

For nearly 70 years, a tacit understanding of sorts had kept the three countries, all of which hold portions of the land of Kashmir, from doing anything drastic to bring about a change to its fragile status quo.

But India upended the agreement by annulling the autonomy and cutting the state into two halves, and as a result, the region, described once by former US President Bill Clinton as "the most dangerous place in the world", descended into a free-for-all.

In early May, a large contingent of Chinese troops crossed an ill-defined border that separates the two countries in Ladakh and hunkered down in trenches and camps, with a large range of artillery guns and heavy equipment flanking the troop encampment. The Chinese intrusion provided a peek into the contours of a new strategic competition unfolding on the roof of the world. In the last decade or so, India has been bolstering its defence facilities across a wide swath of the forbidding glacial landscape with the construction of roads, bridges, tunnels and a large airbase.

After the annexation last year, the Indian political leadership has been making open threats to capture Gilgit-Baltistan, the northern area of Kashmir that went with Pakistan in 1947. What seemed to have forced China's hand was the fear that its $60bn investment in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a part of China's Belt and Road Initiative that wound through Gilgit-Baltistan, could become a victim of any major Indian military thrust into the region. The Chinese move was to forestall any such Indian assault.

The face-off between Chinese and Indian troops in Ladakh might eventually turn out to be only a sideshow to what could become a much bigger military confrontation this year between India and Pakistan along their long border in Kashmir. If Modi were to suffer a debacle in Ladakh, which, whatever way you look at it, is a possibility, for the Chinese do not seem to be in a mood to retreat and the Indian army cannot push out a much superior military force, he would then mobilise the public opinion against Pakistan to boost his own falling ratings.

In February 2019, during his re-election bid for the office of prime minister, Modi ordered Indian warplanes to strike targets inside Pakistan. It was a high-risk retaliation for the suicide bombing of an Indian paramilitary force bus by a young Kashmiri rebel fighter that left at least 40 of the servicemen dead in Pulwama, Kashmir. Although the aerial attack did not achieve anything substantial, and India went on to suffer embarrassment shortly after, when Pakistan carried out a tit-for-tat attack in Kashmir and shot down an Indian fighter plane too, Modi still projected himself as the strongman who could forcefully deal with Pakistan.

Modi's approach to Kashmir is no different, and his strong-arm tactics have fanned an air of desperation in Kashmir. The fear of loss of the homeland and how they could be turned into a minority pervades every Kashmiri home. The new domicile law brought in by the Indian government after removing its special status last year now qualifies thousands of Indians, who have lived in Kashmir for 15 years or studied there for seven, to buy property and settle down in Kashmir.

The effect of the fear of dispossession, though, has galvanised Kashmiris at home and outside to rally together and mount a sustained campaign to bring the attention of the world to the unfolding calamity they are facing. Annexing a contested land might be a new mantra in international relations, but a strong native resistance could be the only means of defence against such onslaught.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Globe, mainstream American media continues its campaign against Vladimir Putin. Americans were never fond of a powerful leadership in Russia, even less when they themselves seldom have powerful leaders themselves.

Maybe that's why the Washington Post has taken its Cold War campaign against China, Russia, and Iran to a new level. In the Sunday edition of its Outlook section, the Post gave front-page coverage to long articles by former ambassador Michael McFaul and former New York Times’ writer Tim Weiner to trumpet Russia’s “constant aggression” and its “brutal Cold War rules.” There was no hint whatsoever of Russian President Vladimir Putin’s efforts to improve Russian-American relations over the past two decades, and no suggestion that the actions of the United States over the past 25 years have significantly contributed to the poor state of relations between Moscow and Washington.

The companion pieces have supportive titles, which suggests an editorial decision to express an authoritative point of view. McFaul’s article is titled “Trump always finds a way to let Putin win….”, and Weiner’s screed follows with “….even when Russia plays by brutal Cold War rules.” Their joint thesis is a simple one: Donald Trump’s complacency has enabled President Putin’s “litany of belligerent acts.” Neither writer notes U.S. actions over the past quarter-century that have worsened the international environment and helped to create a revival of the Cold War. Indeed, they absolve the last four American presidents of any responsibility for the current state of affairs, ignoring their actions that have been consistent with Cold War policymaking. Is anyone going to address the importance of restoring a Russian-American dialogue revolving around arms control and disarmament as well as Third World conflict resolution?

McFaul’s article is particularly interesting in view of his role as the architect of President Barack Obama’s “reset” policy toward Russia, his standing as one of the leading scholars on post-communist Russia, and his appointment as the first non-career diplomat to be U.S. ambassador to the Kremlin. His two-year tour was hardly a success as McFaul, only several days after his arrival in Moscow, chose to invite a number of organizers and prominent participants in the anti-Putin protest movement to the U.S. embassy. McFaul immediately became an Internet celebrity in the tight-knit world of Russian opposition, which demonstrated a lack of awareness of Russian political sensitivities, particularly if the Obama administration was genuinely trying to “reset” relations.

McFaul’s article is totally one-sided. He argues that “Trump has received nothing” from Moscow despite his concessions to the Russian president, citing “no new arms-control treaty, no help in deal with worsening relations with Iran.” But it was Trump who backed away from arms control and disarmament with Russia, abrogating the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty and walking away from the Outer Space Treaty. Conversely, it is Putin who is trying to get back to arms control negotiations, particularly to extend the New START Treaty, which expires in January 2021. Moreover, it is Putin who supports the Iran nuclear accord, and nowhere does McFaul explain what Russian leaders could possibly do to reverse the damage that the Trump administration has done to relations with Iran as well as to political stability in the Persian Gulf.

Weiner is welcome to his opinion that the CIA’s covert action in Afghanistan was the “last great battle of the Cold War,” but the Russians have dealt with genuine facts for the past 25 years that point to U.S. responsibility for the current disarray in Russian-American relations. In the 1990s, it was the United States and President Bill Clinton who decided to expand the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, bringing former Soviet republics into NATO, a betrayal of commitments that President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker gave to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze not to “leap frog” over Germany in order to go into East Europe.

President George W. Bush went one terrible step further by bringing former Soviet republics into NATO; it took German Chancellor Angela Merkel to get him to stop flirting with membership for Ukraine and Georgia. Merkel convinced Bush that introducing Ukraine and Georgia to NATO would violate Putin’s red line regarding NATO membership. Assistant Secretary of State for Europe Victoria Nuland used her cell phone to discuss specific individuals who would be in the government or out. When the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine told Nuland that the European Union would have problems with her intervention, she replied “Fuck the EU.” The Kremlin intercepted the call and had a field day spreading the news. The Russian actions toward Ukraine and Georgia that McFaul and Weiner cite were, in fact, a response to U.S. manipulation of the politics and policies of both nations, which followed Putin’s red-line warnings to the United States.

One of the most severe moves reminiscent of the Cold War was President George W. Bush’s abrogation of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002. It was noteworthy that John Bolton served in influential administration positions in 2002 and 2019, when the ABM Treaty and the INF Treaty, respectively, were abrogated. Bush followed up the abrogation with another offensive maneuver, the deployment of a regional missile defense in Poland and Romania, claiming the defense was designed to counter a possible attack from Iran. This made no sense at the time, and even less sense during the Obama administration when the Iran nuclear accord was completed. Not only has Donald Trump demonstrated no interest in the importuning from Putin regarding the need to return to disarmament negotiations, he has created a Cold War-like Space Force and suggested that U.S. troops to be withdrawn from Germany might end up in Poland. McFaul needs to reconcile the fact that additional U.S. forces will be sent to Poland with his notion that “Trump always finds a way to let Putin win.”

It is customary for the political rhetoric to get heated during a presidential campaign, which will find Donald Trump and Joe Biden vying for honors in the field of national security and militancy, but there should be some balance and context from the mainstream media. The increasingly hard line of the Washington Post on the competition with China, Russia, and Iran suggests that the political contenders will be goaded—and not ameliorated—by the nation’s key newspapers.

The companion pieces have supportive titles, which suggests an editorial decision to express an authoritative point of view. McFaul’s article is titled “Trump always finds a way to let Putin win….”, and Weiner’s screed follows with “….even when Russia plays by brutal Cold War rules.” Their joint thesis is a simple one: Donald Trump’s complacency has enabled President Putin’s “litany of belligerent acts.” Neither writer notes U.S. actions over the past quarter-century that have worsened the international environment and helped to create a revival of the Cold War. Indeed, they absolve the last four American presidents of any responsibility for the current state of affairs, ignoring their actions that have been consistent with Cold War policymaking. Is anyone going to address the importance of restoring a Russian-American dialogue revolving around arms control and disarmament as well as Third World conflict resolution?

McFaul’s article is particularly interesting in view of his role as the architect of President Barack Obama’s “reset” policy toward Russia, his standing as one of the leading scholars on post-communist Russia, and his appointment as the first non-career diplomat to be U.S. ambassador to the Kremlin. His two-year tour was hardly a success as McFaul, only several days after his arrival in Moscow, chose to invite a number of organizers and prominent participants in the anti-Putin protest movement to the U.S. embassy. McFaul immediately became an Internet celebrity in the tight-knit world of Russian opposition, which demonstrated a lack of awareness of Russian political sensitivities, particularly if the Obama administration was genuinely trying to “reset” relations.

McFaul’s article is totally one-sided. He argues that “Trump has received nothing” from Moscow despite his concessions to the Russian president, citing “no new arms-control treaty, no help in deal with worsening relations with Iran.” But it was Trump who backed away from arms control and disarmament with Russia, abrogating the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty and walking away from the Outer Space Treaty. Conversely, it is Putin who is trying to get back to arms control negotiations, particularly to extend the New START Treaty, which expires in January 2021. Moreover, it is Putin who supports the Iran nuclear accord, and nowhere does McFaul explain what Russian leaders could possibly do to reverse the damage that the Trump administration has done to relations with Iran as well as to political stability in the Persian Gulf.

Weiner is welcome to his opinion that the CIA’s covert action in Afghanistan was the “last great battle of the Cold War,” but the Russians have dealt with genuine facts for the past 25 years that point to U.S. responsibility for the current disarray in Russian-American relations. In the 1990s, it was the United States and President Bill Clinton who decided to expand the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, bringing former Soviet republics into NATO, a betrayal of commitments that President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker gave to Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze not to “leap frog” over Germany in order to go into East Europe.

President George W. Bush went one terrible step further by bringing former Soviet republics into NATO; it took German Chancellor Angela Merkel to get him to stop flirting with membership for Ukraine and Georgia. Merkel convinced Bush that introducing Ukraine and Georgia to NATO would violate Putin’s red line regarding NATO membership. Assistant Secretary of State for Europe Victoria Nuland used her cell phone to discuss specific individuals who would be in the government or out. When the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine told Nuland that the European Union would have problems with her intervention, she replied “Fuck the EU.” The Kremlin intercepted the call and had a field day spreading the news. The Russian actions toward Ukraine and Georgia that McFaul and Weiner cite were, in fact, a response to U.S. manipulation of the politics and policies of both nations, which followed Putin’s red-line warnings to the United States.

One of the most severe moves reminiscent of the Cold War was President George W. Bush’s abrogation of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002. It was noteworthy that John Bolton served in influential administration positions in 2002 and 2019, when the ABM Treaty and the INF Treaty, respectively, were abrogated. Bush followed up the abrogation with another offensive maneuver, the deployment of a regional missile defense in Poland and Romania, claiming the defense was designed to counter a possible attack from Iran. This made no sense at the time, and even less sense during the Obama administration when the Iran nuclear accord was completed. Not only has Donald Trump demonstrated no interest in the importuning from Putin regarding the need to return to disarmament negotiations, he has created a Cold War-like Space Force and suggested that U.S. troops to be withdrawn from Germany might end up in Poland. McFaul needs to reconcile the fact that additional U.S. forces will be sent to Poland with his notion that “Trump always finds a way to let Putin win.”

It is customary for the political rhetoric to get heated during a presidential campaign, which will find Donald Trump and Joe Biden vying for honors in the field of national security and militancy, but there should be some balance and context from the mainstream media. The increasingly hard line of the Washington Post on the competition with China, Russia, and Iran suggests that the political contenders will be goaded—and not ameliorated—by the nation’s key newspapers.

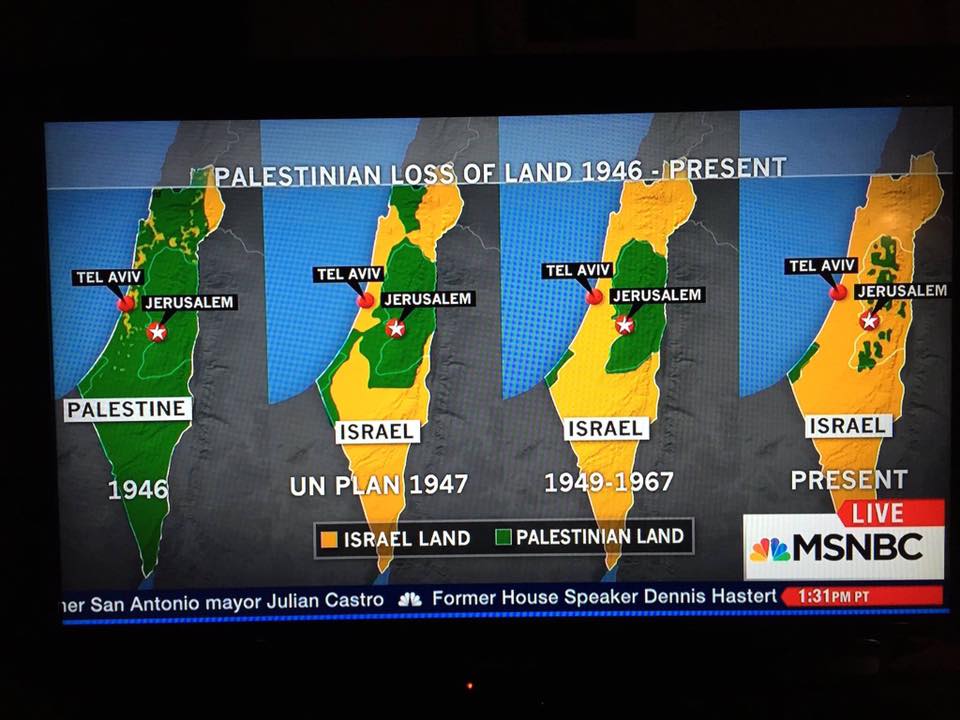

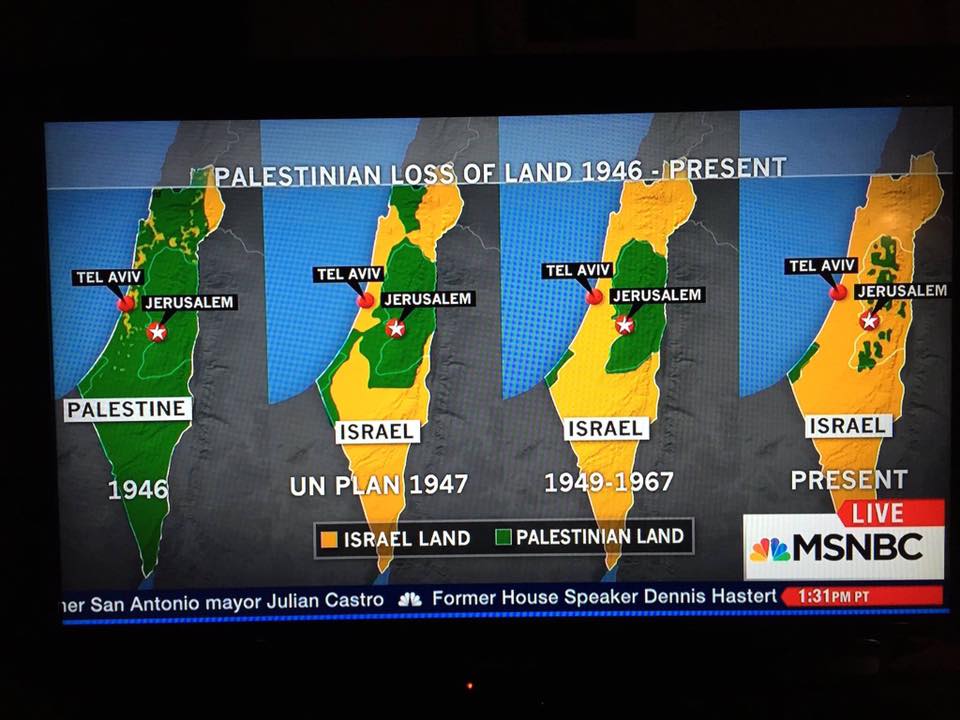

PALESTINA

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário