After 27 million Soviet lives lost, the Red Army defeated Nazism by liberating the concentration camps and capturing Berlin, raising the Soviet flag over the Reichstag, in 1945.

Air Parade on May 8th 2020 to mark 75th anniversary of Victory Day in Moscow.

Seventy five years have passed since the end of World War II.

After more than 30 years of watching “real” war, I obviously have strong views about the fight which statesmen and politicians and liars – the three are, of course, interchangeable, and, most of the time, complementary – regard as their “war” against coronavirus. Both “real” war and viral war (the Covid variety) produce casualties. They produce heroes. They demonstrate human endurance. But they should not be compared.

In the end of the Covid-19 "war", there will be dozens of thousands of human losses, inumerous mourners, sequelae, however, inside and outside our houses, there will be no physical evidence of the damage at all.

We are not going to be faced with this catastrophe when our current “battle” has ended – if it does end, of which more later. When we open all our front doors, our human losses may be great and our economic losses may seem unsupportable, but our physical world will be much the same. Our great institutions, our parliaments, schools, universities, hospitals and town halls and railway stations, our airports and road networks, our water and sewage systems, our very homes will be untouched. They will look exactly the same as they did a few months ago. We will have been spared the worst of real wars.

Let's not be so dramatic, sel-indulgent, and emphasise the big difference between this (Covid-19) and the real thing: the fact that the world outside the front door looks very much the same as it did in Janeuary and February.

That’s why so many people have found themselves willing to break the "house arrest" rules which have been laid down for them. I think that it’s not because they are all bent on suicide, or only selfish, or crazy; it’s because they have taken a look at the great outdoors and have found it much the same as they remembered it. Little by little, they are prepared to risk danger to themselves and others because they can – this phrase is quite deliberate – somehow accept this.

So here, let us return to real wars. One of the most remarkable phenomena of these terrifying conflicts is that ordinary life continues amid the bloodshed and imminent annihilation.

During battles and during fearful moments of wars, people keep on living: getting married, making love, giving birth, buying and selling goods, food and property. Their lives are in danger but they still need property documents, banking funds and lawyers. Amid anarchy, the formal bureaucracy of the law must take its course.

All this – the social events and the property transfers – have to continue because, in the oldest of cliches, life must go on. Just as it does in the global virus war. Our marriages today have few guests, property is bought and sold by email attachments, and funerals – an essential part of normal “life”, I suppose – are still necessarily performed, albeit without the next of kin seeing the dead or even standing close to their coffins.

But there is something noticeable in real wars: that the civilians who suffer amid the fighting also have an extraordinary ability to endure the losses around them. It’s something to do with the idea of society; the idea that it is possible, however appalled by one’s personal circumstances, to understand pain and death as something which approaches normality. Real wars, you see, also move towards what might be termed a “new normal”. Friends and relatives are killed. There is nobody in Palestine, in Lebanon or Syria who has not experienced this shock. But shock is also relative.

During the British occupation of Ireland, which caused the Northern Ireland conflict, the British home secretary Reginald Maudling referred in 1971 to what he called “an acceptable level” of violence. This was inevitably condemned by those who believed that any violence was unacceptable, but his remark made ghoulish sense. Journalists understood exactly what Maudling meant: that the toll of death and bombings could reach a point where they became normal.

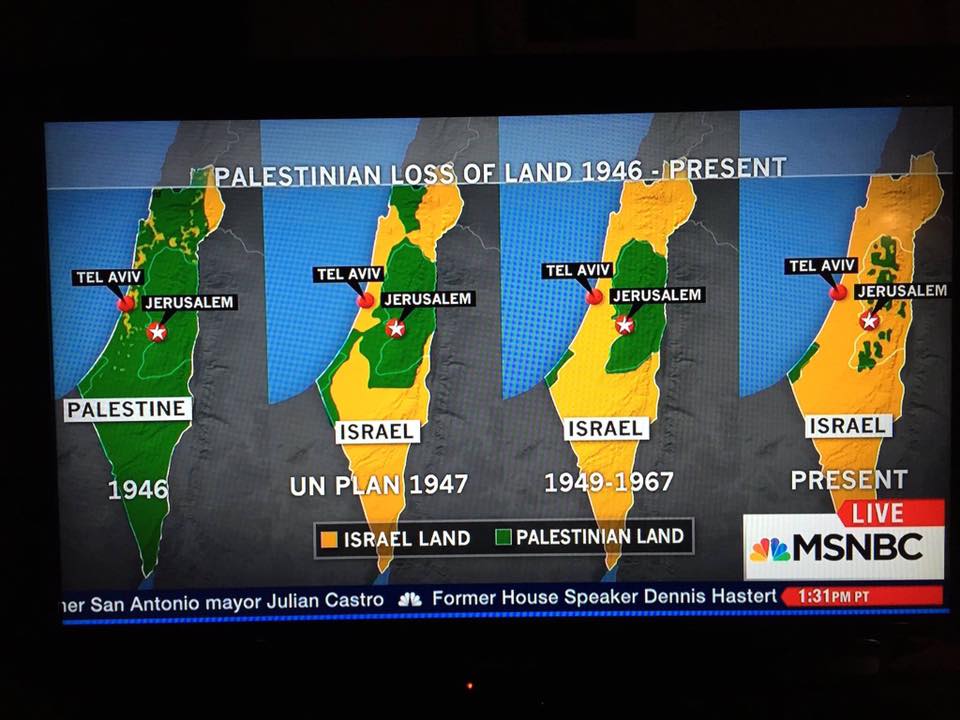

This happens in Palestine, happened in Syria and in Lebanon. During ceasefires, or even without truces, people would go to the beach or to a park to sunbathe or swim at weekends.They risked a carnage, but did it anyway, and carnage came. A week later, the beaches were full again. Many people consent to an “acceptable level” of death. This kind of resilience has been in one sense inspiring – human beings can show themselves unconquerable – but in a different way it is also deeply depressing. If civilians – the public, to use our very western expression – can become inured to death, then the war can go on indefinitely, as it has been going on in Palestine for almost a hundred years. And this, remember, is a war caused by the same human species who are dying in it.

But here I reach a troubling thought. We all know that the current mass "house arrest" of millions of people cannot go on forever. And the current Covid-19 virus will not “end” in the traditional sense that a war comes to its conclusion. There will be no last casualty. But when the figures become lower, and if there is no second visitation from this dreadful thing, and when the daily statistic moves from the hundreds into the dozens and then to the tens per day, there will be no more briefings, far fewer earnest thoughts from health experts and, alas, less remembrance of the sacrifice of nurses and doctors. We may even take bets on when the next round of cuts will be imposed on public health systems.

But the point is that we all – save for those mourning the men and women they loved – have a capacity to absorb death. When european "responsible" governments believe that moment has been reached in this present crisis, they will open the doors and the roads and even the restaurants. The economy must survive.

Presidents and Prime Ministers will announce victory, but this will be untrue. Their people will still be dying. But their deaths will have become normal – like those of cancer or heart attack patients or road accident victims.

And in this way, we will not need to enjoy “herd immunity”. With or without protection from this virus or the next, with or without a vaccine, people all over the world will have become a “herd” in a different sense of the word. They will, as their governments ultimately wish them to become, a herd which is immune to the deaths of others, one which will have absorbed an acceptable level of death amid their own people. They will all have become a little more indurated to the infliction of such suffering, and they will stop squabbling about their governments’ failure to prevent this outrage.

And they will – let us use the disgusting mantra of all politicians – “move on”. They will have “come to terms” with the virus. As so many governments have been doing for so (too) long – and will continue to do.

And we can forget any expensive planning for the next visitation. Until we come across Covid-20 or Covid-22 or Covid-30. Or it comes across us.

Speaking of "wars" and wars, let us not forget that despite Hollywood propaganda, it was the Soviet Red Army that entered Berlin, on foot, in 1945. And it was the same soviet soldiers who liberated the concentration camps in Poland and Ukraine on their way to Germany, altough the pictures were taken by the Americans who arrived behind, once the Nazis had fled or being killed by the Russians.

War is what you see below. A horror. Like daily life in Palestine.

Speaking of "wars" and wars, let us not forget that despite Hollywood propaganda, it was the Soviet Red Army that entered Berlin, on foot, in 1945. And it was the same soviet soldiers who liberated the concentration camps in Poland and Ukraine on their way to Germany, altough the pictures were taken by the Americans who arrived behind, once the Nazis had fled or being killed by the Russians.

War is what you see below. A horror. Like daily life in Palestine.

Leningrad (Saint-Petersbourg - Санкт-Петербyрг) 872 days siege

800.000 Russian civilians in a poulation of 3 million

Stalingrad (Volgograd - Волгогра́д) 2 million Russian civilian and military casualties

Berlin

London

Syria

Gaza

The Listening Post: Coronavirus Communicators

PALESTINA

"On March 23, Germany announced nation-wide measures to prevent the further spread of the coronavirus. People were advised to stay at home and public gatherings were banned; restaurants and pubs were closed. Days earlier, schools were shuttered followed by gyms, cinemas, museums and other public places. And so life began under lockdown.

For many of my German friends, this was the first time in their lives they were experiencing such government-imposed restrictions. For me, the lockdown in Berlin, where I live now, brought back memories from the first Intifada.

I was just a baby when the uprising started in December 1987 in Jabalia refugee camp in Gaza, my birthplace. By the time it ended, I was a school-age boy. Lockdowns, curfews and a variety of restrictions were all I knew for the first six years of my life.

The Intifada broke out after Israeli soldiers killed four Palestinians at a checkpoint at our camp. When crowds of Palestinians went out to protest against the deaths, Israeli soldiers opened fire, killing another Palestinian man.

The killings were just the spark; the real reason was the decades of brutal military occupation and apartheid my people had endured while watching our land being colonised by European and American Jewish settlers arriving from abroad.

The whole of historic Palestine erupted in protest. To Israeli tear gas and bullets, Palestinians responded with slingshots and stones. The Israeli occupation army and Israeli "civilians" killed close to 1,500 Palestinians, more than 300 of them children.

Facing a people-wide uprising that deadly repression could not put out, the Israeli government started imposing various forms of lockdowns to try to control the Palestinian population, which had launched a sustained grassroots resistance campaign.

The curfews would come and go. The Israelis would impose them for days, weeks, even months at a time. According to American scholar Wendy Pearlman, in the first year of the Intifada, the Israeli occupation army put various Palestinian communities under round-the-clock curfews more than 1,600 times.

During those curfews, we would not be allowed to go out. Sometimes, we would run out of food, and my grandmother and aunts would risk their lives to go outside and look for supplies to buy.

Food was scarce, as farmers were not allowed to go to the fields. Many crops lay rotting, with no one to harvest them.

Universities and schools were closed, leaving a whole generation of Palestinian children and youth falling behind on their education. We had no parks, no public gardens to go to and play in. The beach, too, was "closed" by the Israelis.

But the many restrictions, the constant harassment and persistent killings did not bring down the Palestinian spirit. All across historic Palestine, popular resistance committees were established which coordinated various activities to provide for the people. My father, Ismael, was involved in organising the committee in our camp.

Women grew food at homes and on rooftops and founded agricultural cooperatives which they called victory gardens, to create an autonomous Palestinian economy and enable the boycott of Israeli products. Trade committees organised strikes; health committees established makeshift clinics, educational committees set up underground classes. Everyone put in whatever effort they could to help their community and no one was left without communal support.

That, of course, angered the Israelis. I clearly remember, when I was four years old, Israeli soldiers broke into our home and started destroying our belongings. It was a punishment for my father's political activities - one that so many families endured repeatedly.

My father was also often questioned and detained for weeks, sometimes months at a time. During one of these episodes, after an hours-long interrogation, an Israeli commander asked him if he had anything to say. My father answered he wanted to get a permit to be allowed to go to his bees. The commander laughed, saying, "You might go to prison now, and you are thinking of your bees?" My father responded that he must take care of them or they would die, and those bees fed his family. My father was detained that time for a week. The bees did not survive.

We became reliant on my mother's salary. She was working as a nurse in an UNRWA clinic. She had to go to work every day even during curfew, so she had a permit to cross the Israeli checkpoints. She would treat many of the children who were beaten or injured by Israeli soldiers in our camp. According to Save the Children NGO, in the first two years of the uprising, between 23,600 and 29,900 sought medical help for injuries.

In the summer of 1991, my mother went into labour. As there were very few phones in the refugee camp at the time, we could not call an ambulance; besides, no ambulances were allowed into the camp under the curfew. As a result, my mother was forced to walk to the UNRWA clinic, a kilometre away. She made her way leaning on my grandmother, who was waving a white scarf, hoping the Israeli soldiers would not shoot at them.

Not far from our home, Israeli soldiers pointed their guns at them and made them stop. They started questioning my mother about why they were breaking the curfew, even though it was obvious she was about to give birth; she could hardly stand on her feet. "It was a frightening moment," my mother would recall later. "I was trying to protect my belly away from their guns as the painful contractions came one after the other."

The soldiers eventually let them go, and that evening my mother gave birth to my sister, Shahd. In the morning they braved the curfew again and walked back home. We were all happy to see them and my baby sister.

Life was extremely difficult for us, but my parents always recall the Intifada as a time of liberation, often saying, "We did not give up on our resistance. We did not become subdued victims." Indeed, Palestinians set an example for a grassroots struggle rarely seen at that time.

And here I am today, three decades later, again under a lockdown - but a much different one. There are no rubber bullets, live ammunition or tear gas canisters shot at people walking in the streets; there are no checkpoints; no violent repression, the way I have experienced in Palestine.

Like my German friends, I too am anxious about the situation in Germany, but most of the time, my mind is wandering towards Gaza.

My family still lives in the densely-populated Jabalia refugee camp where social distancing is impossible. Our camp has more than 113,000 people living in an area that covers a bit more than half a square kilometre.

Already 17 people tested positive in Gaza. The local authorities and international organisations have warned of an impending catastrophe.

I can feel my parents' worries, especially my mother, who is still working in the UNRWA clinic. She takes a big risk every time she goes to work, where she sees dozens of people every day. Gaza's healthcare system has been damaged by years of a suffocating siege imposed by Israel and Egypt on the strip and by multiple destructive wars waged by the Israeli military against my people. It is extremely vulnerable and a major coronavirus outbreak would spell disaster.

Unlike Germany [and Europe, in generalk], where the government is already relaxing lockdown measures and talking about a return to "normal" at some point in the future, in Gaza, my people are preparing for the worst. The death and suffering this epidemic could inflict on Palestinians will be yet another entry in the long list of war crimes the Israelis have committed against us and it will weigh heavily on the conscience of the international community which has abandoned us.

These days I keep asking myself: Has the world forgotten us, having accepted our life in inhumane conditions? Or will it do something this time to hold Israel accountable?"

Majed Abusalama, is an award winning journalist, scholar, campaigner and human rights defender from Palestine.

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário