Now, let's move far - geographically - from Britain and get to the point of this post.

The fallout from the September attack on Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facilities is continuing to reverberate throughout the Middle East, sidelining old enmities—sometimes for new ones—and re-drawing traditional alliances. While Turkey’s recent invasion of northern Syria is grabbing the headlines, the bigger story may be that major regional players are contemplating some historic re-alignments.

The fallout from the September attack on Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facilities is continuing to reverberate throughout the Middle East, sidelining old enmities—sometimes for new ones—and re-drawing traditional alliances. While Turkey’s recent invasion of northern Syria is grabbing the headlines, the bigger story may be that major regional players are contemplating some historic re-alignments.

After years of bitter rivalry, the Saudis and the Iranians are considering how they can dial down their mutual animosity. The formerly powerful Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) of Persian Gulf monarchs is atomizing because Saudi Arabia is losing its grip. And Washington’s former domination of the region appears to be in decline.

Some of these developments are long-standing, pre-dating the cruise missile and drone assault that knocked out 50 percent of Saudi Arabia’s oil production. But the double shock—Turkey’s lunge into Syria and the September missile attack—is accelerating these changes.

Pakistani Prime Minister, Imran Khan, recently flew to Iran and then on to Saudi Arabia to lobby for détente between Teheran and Riyadh and to head off any possibility of hostilities between the two countries. “What should never happen is a war,” Khan said, “because this will not just affect the whole region…this will cause poverty in the world. Oil prices will go up.”

According to Khan, both sides have agreed to talk, although the Yemen War is a stumbling block. But there are straws in the wind on that front, too. A partial ceasefire seems to be holding, and there are back channel talks going on between the Houthis and the Saudis.

The Saudi intervention in Yemen’s civil war was supposed to last three months, but it has dragged on for over four years. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) was to supply the ground troops and the Saudis the airpower. But the Saudi-UAE alliance has made little progress against the battle-hardened Houthis, who have been strengthened by defections from the regular Yemeni army.

Air wars without supporting ground troops are almost always a failure, and they are very expensive. The drain on the Saudi treasury is significant, and the country’s wealth is not bottomless.

Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman - aka MBS - is trying to shift the Saudi economy from its overreliance on petroleum, but he needs outside money to do that and he is not getting it. The Yemen War—which, according to the United Nations is the worst humanitarian disaster on the planet, although I still thnik it comes just after the ethnic cleansing of Palestine—and the Prince’s involvement with the murder and dismemberment of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, has spooked many investors.

Without outside investment, the Saudi’s have to use their oil revenues, but the price per barrel is below what the Kingdom needs to fulfill its budget goals, and world demand is falling off. The Chinese economy is slowing— the trade war with the US has had an impact—and European growth is sluggish. There is a whiff of recession in the air, and that’s bad news for oil producers.

Riyadh is also losing allies. The UAE is negotiating with the Houthis and withdrawing their troops, in part because the Abu Dhabi has different goals in Yemen than Saudi Arabia, and because in any dustup with Iran, the UAE would be ground zero. US generals are fond of calling the UAE “little Sparta” because of its well trained army, but the operational word for Abu Dhabi is “little”: the Emirate’s army can muster 20,000 troops, Iran can field more than 800,000 soldiers.

Saudi Arabia’s goals in Yemen are to support the government-in-exile of President Rabho Mansour Hadi, control its southern border and challenge Iran’s support of the Houthis. The UAE, on the other hand, is less concerned with the Houthis but quite focused on backing the anti-Hadi Southern Transitional Council, which is trying to re-create south Yemen as a separate country. North and south Yemen were merged in 1990, largely as a result of Saudi pressure, and it has never been a comfortable marriage.

Riyadh has also lost its grip on the Gulf Cooperation Council. Oman, Kuwait, and Qatar continue to trade with Iran in spite of efforts by the Saudis to isolate Teheran,

The UAE and Saudi Arabia recently hosted Russian President Vladimir Putin, who pressed for the 22-member Arab League to re-admit Syria. GCC member Bahrain has already re-established diplomatic relations with Damascus. Putin is pushing for a multilateral security umbrella for the Middle East, which includes China.

“While Russia is a reliable ally, the US is not,” is what is said and understood in all Arab capitals. And while many in the region have no love for Syria’s Assad, they respect Vladimir Putin for sticking by Russia’s ally.

The Arab League—with the exception of Qatar—denounced the Turkish invasion and called for a withdrawal of Ankara’s troops. Qatar is currently being blockaded by Saudi Arabia and the UAE for pursuing an independent foreign policy and backing a different horse in the Libyan civil war. Turkey is Qatar’s main ally.

Russia’s 10-point agreement with Turkey on Syria has generally gone down well with Arab League members, largely because the Turks agreed to respect Damascus’s sovereignty and eventually withdraw all troops. Of course, “eventually” is a shifty word, especially because Turkey’s goals are hardly clear.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan wants to drive the Syrian Kurds away from the Turkish border and move millions of Syrian refugees into a strip of land some 19 miles deep and 275 miles wide. The Kurds may move out, but the Russian and Syrian military—filling in the vacuum left by President Trump’s withdrawal of American forces—have blocked the Turks from holding more than the border and one deep enclave, certainly not one big enough to house millions of refugees.

Erdogan’s invasion is popular at home—nationalism plays well with the Turkish population and most Turks are unhappy with the Syrian refugees—but for how long? The Turkish economy is in trouble and invasions cost a lot of money. Ankara is using proxies for much of the fighting, but without lots of Turkish support those proxies are no match for the Kurds—let alone the Syrian and Russian military.

That would mainly mean airpower, and Turkish airpower is restrained by the threat of Syrian anti-aircraft and Russian fighters, not to mention the fact that the Americans still control the airspace. The Russians have deployed their latest fifth-generation stealth fighter, the SU-57, and a number of MiG-29s and SU-27s, not planes the Turks would wish to tangle with. The Russians also have their new mobile S-400 anti-aircraft system, and the Syrians have the older, but still effective, S-300s.

In short, things could get really messy if Turkey decided to push their proxies or their army into areas occupied by Russian or Syrian troops. There are reports of clashes in Syria’s northeast and casualties among the Kurds and Syrian Army, but a serious attempt to push the Russians and the Syrians out seems questionable.

The goal of resettling refugees is unlikely to go anywhere. It will cost some US$53 billion to build an infrastructure and move two million refugees into Syria, money that Turkey doesn’t have. The European Union has made it clear it won’t offer a nickel, and the UN can’t step in because the invasion is a violation of international law.

When those facts sink in, Erdogan might find that Turkish nationalism will not be enough to support his Syrian adventure if it turns into an occupation.

The Middle East that is emerging from the current crisis may be very different than the one that existed before those cruise missiles and drones tipped over the chessboard. The Yemen War might finally end. Iran may, at least partly, break out of the political and economic blockade that Saudi Arabia, the US and Israel has imposed on it. Syria’s civil war will recede. And the Americans, who have dominated the Middle East since 1945, will become simply one of several international players in the region, along with China, Russia, India and the European Union.

On the other hand, the sectarian and ethnic civil wars that have ravaged a large part of theMiddle East over the past 40 years are coming to an end. Replacing them is a new type of conflict in which protests akin to popular uprisings rock kleptocratic elites that justify their power by claiming to be the defenders of communities menaced by extreme violence or extinction.

In October, it had been three years since the last big ISIS bomb had exploded in its streets killing great numbers, something that used to happen with appalling frequency. One could even think that peace had finally come to Iraq's capital. But it hadn't. The gun shots came from Iraq's security forces and in minutes there were a dozen of protesters dead in Tahrir Square.

The death toll was to get a great deal worse than that: the official toll is 157 dead and 6,100 wounded, but doctors told me at the time that the real number of fatalities was far higher. The protesters, initially small in numbers, had wanted jobs, an end to corruption and improved essential services such as a better water and electricity. But somebody in government security, supplemented by pro-Iranian paramilitaries, had considered these demands for social and economic justice as a threat to the political status quo to be suppressed with live rifle fire, a curfew on the seven million inhabitants of Baghdad, and a shutdown of the internet.

Repression worked briefly, but such is the depth of rage against the theft of $450bn from Iraq’s oil revenues since 2003 that the protests were bound to break out again, as they did with 23 dead and the offices of a provincial governor set on fire.

A few days later masses of protesters in Beirut not Baghdad, though with a similar motivation went to the streets showing their anger against a ruling class saturated by corruption while failing to provide the basic services to the population. Encouragingly, in both Lebanon and Iraq, the leaders of different communities are finding that their followers increasingly view them as mafiosi and ignore appeals for communal solidarity.

It is a period of transition and one should never underestimate the ability of embattled communal leaders to press the right sectarian buttons in order to divide opposition to their predatory misrule.

When I first knew the region in the 1980's, there was a Lebanese civil war between a mosaic of communities defined by religion and ethnicity. In later years in Iraq, I watched divisions between Sunni and Shia grow and produce sectarian bloodbaths after the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003. Popular protests in Syria in 2011 swiftly turned into a sectarian and ethnic civil war of extraordinary ferocity that may now be coming to an end.

This is not because combatants on all sides have come to see the error of their ways or that they have suddenly noticed for the first time that their leaders are for the most part criminalised plutocrats. It is rather because winners and losers have emerged in these conflicts, so those in power can no longer divert attention from their all-embracing corruption by claiming that their community is in danger of attack from merciless foes.

Victors and vanquished has long been identifiable in Lebanon and became clear in Iraq with the capture of Mosul and the defeat of Isis in 2017. The winners and losers in the Syrian civil war have become ever more apparent over the last month as Bashar al-Assad, Russia and Iran take control of almost the whole country.

The Iraqi and Syrian Kurds had been able to create and expand their own quasi-states when central governments in Baghdad and Damascus were weak and under assault by Isis. The statelets were never going to survive the defeat of the Isis caliphate: the Iraqi Kurds lost the oil province of Kirkuk to the Iraqi army in 2017 and the Syrian Kurds have just seen their quasi-state of Rojava squeezed to extinction by the Turks on one side and the Syrian government on the other after Donald Trump withdrew US military protection.

The fate of the Kurd is a tragedy but an inevitable one. Once Isis had been defeated in the siege of Raqqa in 2017 there was no way that the US was going to maintain a Kurdish statelet beset by enemies on every side. For all their accusations of American treachery, the Kurdish leaders chose to turn to Washington because they knew that Russia and Assad were never going to underwrite a semi-independent Kurdish state.

A problem in explaining developments in the Middle East over the last three years is that the US foreign policy establishment supported by most of the US and European media blame all negative developments on Donald Trump. This is a gross over-simplification when it is not wholly misleading. His abrupt and cynical abandonment of the Kurds to Turkey may have multiplied their troubles, but extracting the small US military from eastern Syria was sensible enough because it was over-matched by four dangerous and determined opponents: Turkey, Iran, Russia and the Assad government.

The final outcome of the multiple Syrian wars is now in sight: Turkey will keep a small, unstable enclave in Syria but the rest of the Syrian-Turkish border will be policed by Russian and Syrian government troops who will oversee the YPG withdrawal 21 miles to the south. The most important question is how far the Kurdish civilian population, who have fled the fighting, will find it safe enough to return. A crucial point to emerge from the meeting between Vladimir Putin and Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently in Sochi is that Turkey is tiptoeing towards implicitly recognising the Assad government backed by Russia as the protector of its southern border against the YPG. This makes it unlikely that Ankara will do much to stop a Russian-Syrian government offensive to take, probably a slice at a time, the last stronghold of the Syrian armed opposition in Idlib.

The ingredient that made communal religious and sectarian hatreds so destructive in the past in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq is that they opened the door to foreign intervention. Local factions became the proxies of outside countries pursuing their own interests which armed and financed them. For the moment at least, it seems that no foreign power has an interest in stirring the pot in this northern tier of the Middle East, the zone of war for 44 years, and there is just a fleeting chance of a durable peace.

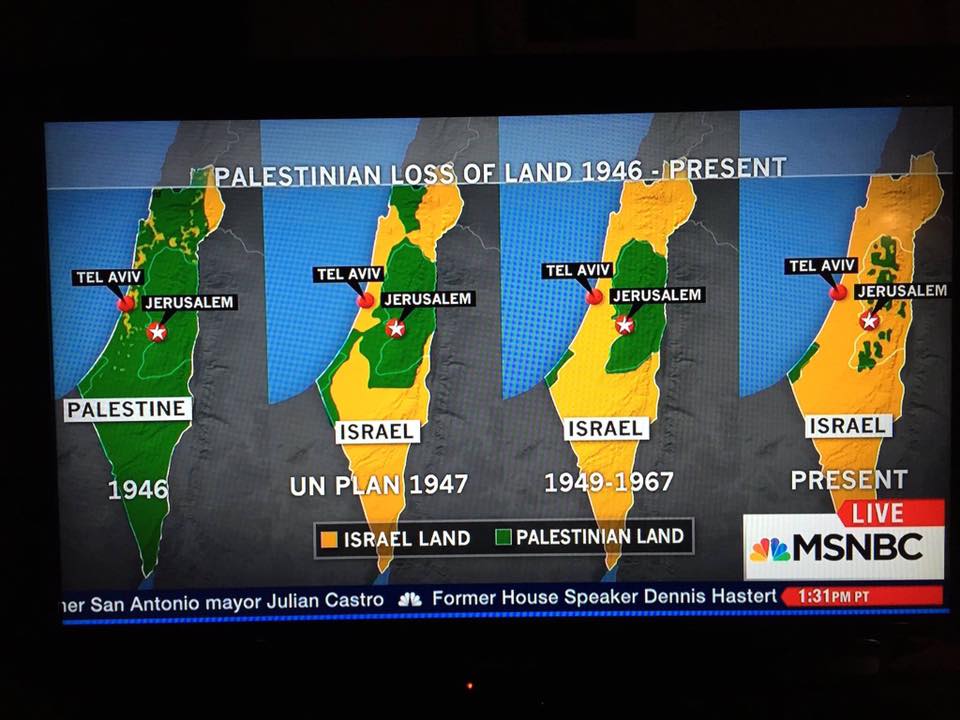

PALESTINA

It has been a week of appalling abuses committed by Israeli soldiers in the West Bank – little different from the other 2,670 weeks endured by Palestinians since the occupation began in 1967.

The difference this past week was that several entirely unexceptional human rights violations that had been caught on film went viral on social media.

One shows a Palestinian father in the West Bank city of Hebron leading his son by the hand to kindergarten. The pair are stopped by two heavily armed soldiers, there to help enforce the rule of a few hundred illegal Jewish settlers over the city’s Palestinian population.

The soldiers scream at the father, repeatedly and violently push him and then grab his throat as they accuse his small son of throwing stones. As the father tries to shield his son from the frightening confrontation, one soldier pulls out his rifle and sticks it in the father’s face.

It is a minor incident by the standards of Israel’s long-running belligerent occupation. But it powerfully symbolises the unpredictable, humiliating, terrifying and sometimes deadly experiences faced daily by millions of Palestinians.

A video of another such incident emerged last week. A Palestinian man is ordered to leave an area by an armed Israeli policewoman. He turns and walks slowly away, his hands in the air. Moments later she shoots a sponge-tipped bullet into his back. He falls to the ground, writhing in agony.

It is unclear whether the man was being used for target practice or simply for entertainment.

The reason such abuses are so commonplace is that they are almost never investigated – and even less often are those responsible punished.

It is not simply that Israeli soldiers become inured to the suffering they inflict on Palestinians daily. It is the soldiers’ very duty to crush the Palestinians’ will for freedom, to leave them utterly hopeless. That is what is required of an army policing a population permanently under occupation.

The message is only underscored by the impunity the soldiers enjoy. Whatever they do, they have the backing not only of their commanders but of the government and courts.

Just that point was underlined late last month. An unnamed Israeli army sniper was convicted of shooting dead a 14-year-old boy in Gaza last year. The Palestinian child had been participating in one of the weekly protests at the perimeter fence.

Such trials and convictions are a great rarity. Despite damning evidence showing that Uthman Hillis was shot in the chest with a live round while posing no threat, the court sentenced the sniper to the equivalent of a month’s community service.

In Israel’s warped scales of justice, the cost of a Palestinian child’s life amounts to no more than a month of extra kitchen duties for his killer.

But the overwhelming majority of the 220 Palestinian deaths at the Gaza fence over the past 20 months will never be investigated. Nor will the wounding of tens of thousands more Palestinians, many of them now permanently disabled.

There is an equally disturbing trend. The Israeli public have become so used to seeing YouTube videos of soldiers – their sons and daughters – abuse Palestinians that they now automatically come to the soldiers’ defence, however egregious the abuses.

The video of the father and son threatened in Hebron elicited few denunciations. Most Israelis rallied behind the soldiers. Amos Harel, a military analyst for the liberal Haaretz newspaper, observed that an “irreversible process” was under way among Israelis: “The soldiers are pure and any criticism of them is completely forbidden.”

When the Israeli state offers impunity to its soldiers, the only deterrence is the knowledge that such abuses are being monitored and recorded for posterity – and that one day these soldiers may face real accountability, in a trial for war crimes.

But Israel is working hard to shut down those doing the investigating – human rights groups.

For many years Israel has been denying United Nations monitors – including international law experts like Richard Falk and Michael Lynk – entry to the occupied territories in a blatant bid to stymie their human rights work.

Last week Human Rights Watch, headquartered in New York, also felt the backlash. The Israeli supreme court approved the deportation of Omar Shakir, its Israel-Palestine director.

Before his appointment by HRW, Shakir had called for a boycott of the businesses in illegal Jewish settlements. The judges accepted the state’s argument: he broke Israeli legislation that treats Israel and the settlements as indistinguishable and forbids support for any kind of boycott.

But Shakir rightly understands that the main reason Israel needs soldiers in the West Bank – and has kept them there oppressing Palestinians for more than half a century – is to protect settlers who were sent there in violation of international law.

The collective punishment of Palestinians, such as restrictions on movement and the theft of resources, was inevitable the moment Israel moved the first settlers into the West Bank. That is precisely why it is a war crime for a state to transfer its population into occupied territory.

But Shakir had no hope of a fair hearing. One of the three judges in his case, Noam Sohlberg, is himself just such a lawbreaker. He lives in Alon Shvut, a settlement near Hebron.

Israel’s treatment of Shakir is part of a pattern. In recent days other human rights groups have faced the brunt of Israel’s vindictiveness.

Laith Abu Zeyad, a Palestinian field worker for Amnesty International, was recently issued a travel ban, denying him the right to attend a relative’s funeral in Jordan. Earlier he was refused the right to accompany his mother for chemotherapy in occupied East Jerusalem.

And last week Arif Daraghmeh, a Palestinian field worker for B’Tselem, an Israeli human rights group, was seized at a checkpoint and questioned about his photographing of the army’s handling of Palestinian protests. Daraghmeh had to be taken to hospital after being forced to wait in the sun.

It is a sign of Israel’s overweening confidence in its own impunity that it so openly violates the rights of those whose job it is to monitor human rights.

Palestinians, meanwhile, are rapidly losing the very last voices prepared to stand up and defend them against the systematic abuses associated with Israel’s occupation. Unless reversed, the outcome is preordained: the rule of the settlers and soldiers will grow ever more ruthless, the repression ever more ugly.

Daily Life Under Occupation

BRASIL

O chargista/cartunista brasileiro Carlos Latuff dá uma lição de democracia aos parlamentares na Comissão de Cultura da Câmara.

AOS FATOS:Todas as declarações de Bolsonaro, checadas

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário