In this distressing moment for Kashmir, on may want to remember where all this mess came from.

To those who don't remember, more than 70 years ago today, the Indian subcontinent was divided by its British colonial rulers into two nation-states - India and Pakistan. The Partition sparked three wars, paved the way for the creation of Bangladesh, and transformed Kashmir into one of the world's most militarised zones. It is the single most defining event in the history of the region to this day.

In the state of Punjab, which was one of the two states physically divided by the new border, the Partition is interwoven into the very psyche of society. It is part of the collective memory, state discourse, and family histories. There is no escaping what happened there all those years ago. It is true for people living in different corners of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh today.

But today, the Partition continues to be imagined and reimagined constantly across borders and even within the same nation. Some stories of the Partition are purposefully perpetuated while others are silenced or conveniently forgotten in national discourses.

There is not a singular narrative of the Partition. In fact, it is possible to say that the story of the Partition itself has been "partitioned" over the years across the arbitrarily drawn borders that have since divided the subcontinent.

In Pakistan, for instance, the events of 1947 are seen as the birth of a new nation. While people suffered immense loss and endured horrific violence, which left an indelible mark on their psyche, the national discourse is overwhelmingly focused on the founding of the Pakistani state.

Loss is mostly mentioned in a way that beefs up hostility towards India and reinforces the notion that the partition and the creation of Pakistan were inevitable and must be celebrated. Consequently, violence is portrayed as one-sided and perpetrated by Hindus and Sikhs only, who are equated with Indians, while any atrocities carried out by Muslims are regarded lightly if not dismissed altogether.

This selective narrative about violence is institutionalised in Pakistani textbooks, media and museums. For instance, state-endorsed textbooks include statements such as "Hindus can never become the true friends of Muslims" and "Hindus started the genocide of Muslims", often describing the community as "scheming" and "cunning".

In the Army Museum in Lahore, which opened in 2017, the gallery on the Partition speaks of "rape and abduction of Muslim women" at the hands of Hindus and Sikhs, with no mention of crimes committed by Muslims. This despite the fact that Lahore itself, which had a significant Sikh and Hindu population prior to the Partition, witnessed violence by all sides.

The Partition then, in a sense, is synonymous with "independence from India" in the Pakistani subconsciousness. As the Pakistani school curriculum pays little attention to the actions of the British on the subcontinent, not many people think of the end of colonial subjugation when they think of 1947.

In the schools that I work in Pakistan, students frequently tell me that they celebrate Pakistan's independence from not the British Empire but "Hindu India" every August.

As Pakistan celebrates the "making of the motherland", every August India remembers the Partition as the "breakup of the motherland". There, Children are taught that while Indian leaders never wanted the Partition, the Muslim League had insisted on the creation of a separate Muslim nation.

This simplistic narrative, accepted as an indisputable truth by many Indians, brushes over the intricacies of pre-Partition politics, particularly the different attempts made by the leader of the League, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, to carve out space for Muslims in an undivided India. It ignores the fact that the Partition was a result of rising Muslim separatist politics and the growing strength of the Muslim League on one hand and Hindu communal politics and Congress's desire to maintain hegemony on the other.

In India, the emphasis on the Muslim demand for Pakistan overshadows these other political realities. In the mainstream discourse, it is solely the Muslims who are seen to have "broken" the country.

The same narrative is also used in contemporary communal politics, where Muslims are told to "go back to Pakistan", while conversions of Muslims and Christians to Hinduism under the guise of "ghar wapsi" (or homecoming) are carried out in an attempt to "purify" India. The idea behind such efforts is grounded in the notion that non-Hindus, particularly Muslims, cannot be loyal to the Indian nation.

While the events of 1947 are regularly remembered in India and Pakistan, in Bangladesh, the third child of the Partition, there is almost complete silence on the subject. Even though Bengal suffered significant bloodshed during the Partition, the cataclysmic event appears to hold little importance in the country today. If at all, it is remembered as a delay in the realisation of "actual" independence, which was gained in 1971.

Textbooks gloss over the event, with the stories of 1971 overshadowing everything else. While the Muslim League was formed in Dhaka and the state of Bengal had played an instrumental role in the creation of Pakistan, in the post-Partition years the party and its politicians deprived those from East Pakistan of their economic, social and political rights. For this reason, today, the Muslim League is seen as an anti-hero in Bangladesh.

The story of the Partition, with all its perceived contradictions and complicated nuances, does not fit well into the simple and straight-forward national history of Bangladesh that is being promoted by the state. This is why the discussion about the Partition has come to be hushed and silenced, with the event only being remembered as an insignificant and even irritating footnote in popular history.

Bangladeshis today prefer to focus on other parts of their recent history - parts that easily reinforce their feelings of national pride and unity. The 1952 killing of students demonstrating for the recognition of Bengali as a state language, for example, currently holds more importance in the collective imagination of Bangladesh than the events of 1947.

These different perceptions of the Partition - of loss, triumph and discomfort - have continued to dominate and dictate national policies and strategic thinking in all three countries years after 1947. For instance, textbooks in Pakistan state that the 1971 war - which resulted in the birth of Bangladesh - was an Indian conspiracy to break up Pakistan because it could never truly stomach the Partition. It is treated as a bilateral Indo-Pakistani conflict with little regard to Bengali grievances and the long struggle for rights and emancipation in East Pakistan.

Indians see the 1971 war differently. The late Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, for example, said once that the creation of Bangladesh proved the notion that Muslims and Hindus were two separate nations and needed their own separate homelands wrong, implying that the very idea Pakistan has adopted as its raison d'etre was mistaken. In contrast, for Bangladeshis, 1971 is not an Indo-Pak war but rather a war of liberation, popularly perceived as a culmination of a people's struggle.

Similarly, the Partition is interpreted differently vis-a-vis Kashmir. In India, genuine Kashmiri grievances are ignored and the movement for independence in Kashmir is only seen through the lens of "Pakistan-sponsored terrorism" which is bent on breaking of an integral part of India just like it had broken up the motherland in 1947.

By contrast, the contested territory is perceived as the "unfinished agenda of the Partition" in Pakistan, another "triumph" in the waiting. Between these two competing narratives, Kashmir remains the greatest casualty of the failure of India and Pakistan to resolve their issues with the past.

Just as the narratives of the Partition remain contested in all three countries, so does the memory of the colonial past. In India, colonialism is remembered, but only selectively, to serve as a justification for the Partition. The famous "divide and rule" policy of the British remains central to the discourse and is used to explain "the exploitation of Muslims" by the colonial powers that pitted one community against the other, and thereby led to the creation of Pakistan. While the British indeed crystallised communal identities and exacerbated communal tensions, by focusing on the instruments of divide and rule and putting the blame solely on the British, Indian leadership's failure in keeping the country together are conveniently sidelined as are the communal faultlines that existed prior to the arrival of the British.

In comparison, Pakistani discourse undermines colonial history and pays little attention to British efforts to divide and drive tensions in the multicultural society. The emphasis is on how Muslims and Hindus were always two separate nations and so the British did not need to "divide" the already divided communities. Focusing on the colonial period thus holds little relevance to national politics in the country today. In Bangladesh too, colonial history is subservient to the politics and history of 1971. Pakistan is the dominant enemy, the British a faded memory.

In all three countries, which were all once ruled and exploited by the British, the colonial legacy is yet to be explored in its entirety. There has been a whitewashing of history, the ruins of colonialism selectively used to reinforce each country's Partition narrative or lack thereof but never fully comprehended. Seventy-two years after the Partition, at a time when the region is embroiled in conflict and violence, most recently in Kashmir, it is imperative to revisit the colonial past and its ongoing effect. Without an understanding of the British period and its role in dividing India in 1947, any discourse on the Partition and its repercussions will remain incomplete. A careful and comprehensive study of the British empire and the way in which it changed the social fabric of society could be a critical starting point for mending any fissures left behind by colonialism and the resulting Partition.

As to Kashmir struggle, it didn not start with the partition in 1947.

On August 5, India's Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government issued a surprise executive decree stripping away the autonomy that the state of Jammu and Kashmir was granted in exchange for joining the Indian union after independence in 1947.

Since the decree, Indian authorities also imposed an unprecedented lockdown in the region, cutting off all communication lines, restricting movement and putting prominent Kashmiri politicians under house arrest.

The government's decision to revoke Article 370 of India's constitution, which ensured the Muslim-majority state its own constitution and independence over all matters except foreign affairs, defence and communications, was undoubtedly the most far-reaching political move on the disputed region in the last seven decades. However, neither the Indian government's decision to impose direct rule from New Delhi, nor its attempts to silence the Kashmiri cries for freedom and dignity is anything new.

A brief look back in history makes it evident that Kashmir's oppression and colonial exploitation started long before the formation of modern India. Ever since its annexation by the Mughal empire in 1589 AD, Kashmir has never been ruled by Kashmiris themselves. After the Mughals, the region was ruled by the Afghans (1753-1819), Sikhs (1819-46), and the Dogras (1846-1947) until the Indian and Pakistani states took over.

The Mughals, who did nothing to alleviate the region's poverty or help it fight famines, instead built hundreds of gardens in Kashmir, converting it into a luxurious summer refuge for the rich. The Afghans not only sent Kashmiri people to Afghanistan as slaves, but also imposed extortionate taxes on the region's famed shawl weavers, causing the shawl industry to shrink in size. Next came the Sikhs, who, according to the British explorer William Moorcroft, treated the Kashmiris "little better than cattle".

The discrimination Kashmir's Muslim majority is still facing to this day also came to the fore for the first time during the Sikh rule. Back then, the murder of a native by a Sikh was punished with a fine of 16 to 20 Kashmiri rupees to the government, of which 4 rupees would go to the family of the deceased if the victim is a Hindu, and only 2 rupees if the deceased is a Muslim.

And in 1846, when the British East India Company defeated the Sikh Empire in the first Anglo-Sikh war, Kashmir was sold to the Dogras as if it was not the home of millions of people but just a "commodity". Gulab Singh, a Dogra, who served as the ruler of Jammu in the Sikh Empire, chose to side with the British in the Anglo-Sikh war. After the war, the East India Company "sold" Kashmir to Gulab Singh for a lump sum of 7.5 million rupees to reward his loyalty.

Gulab Singh and the successive Dogra rulers, who then had a free pass over the Kashmir valley, imposed further extortionate taxes on the Kashmiris in an attempt to raise the 7.5 million rupees they had paid to buy Kashmir. Moreover, as a mark of their continued loyalty, the Dogra rulers catered to continued British demands for money and muscle. Under the Dogra rule, Kashmiris were forced to fight in all of Britain's wars, including the two world wars.

The Dogra rule was possibly the worst phase in terms of the economic extortion in Kashmir. Most of the peasants were landless since Kashmiris were banned from holding any land. About 50-75 percent of cultivated crops went to the Dogra rulers, leaving the working class with practically no control over the produce. The Dogra rulers also reintroduced the begar (forced labour) system under which the state could employ workers for little to no payment. Not only every imaginable profession was taxed, but Kashmiri Muslims were also forced to pay a tax if they wished to get married too. The absurdity of the exorbitant tax system reached a new high when something called "zaildari tax" was introduced to pay for the cost of taxation itself...

During the Dogra rule, Kashmiri Pandits - native Hindus of the Kashmir Valley - were slightly better off than the Kashmiri Muslims, perhaps as a result of the administration's pro-Hindu bias. They were allowed to have more upper-class jobs and work as teachers and civil servants. This meant that amongst a predominantly Muslim population, the so-called "petite bourgeois" was dominated by the Hindus. The Dogra regime also replaced Koshur with Urdu as the official language in the region, making it even harder for the Koshur-speaking Kashmiri Muslims to break free from poverty.

Therefore, the history of Kashmir's Muslims often intersects with the history of the working class in the valley. In fact, throughout the Dogra rule in Kashmir, the resistance against the oppressive regime was shaped by class as much as religion.

The workers' resistance against the Dogras kicked off as early as in 1865, when Kashmiri shawl weavers agitated to improve their work conditions. The regime brutally crushed the uprising and in the three decades following the protest, the number of Kashmiri shawl weavers decreased from 28,000 to just over 5,000. Despite the setback, however, Kashmiri workers continued to fight for their rights. in 1924, workers from a Srinagar silk factory went on a strike for better working conditions.

In 1930, some young, left-wing Muslim intellectuals formed the Reading Room Party to get together and explore a way forward for the Jammu and Kashmir that is free of autocracy and oppression. They soon started organising meetings in mosques, and slowly this "political consciousness" started to spread from the intelligentsia to the middle classes. In time, they moved on from mosques to larger scale open meetings.

Noting this growing spirit of revolt among the Muslim community, in 1931, the Dogras approved the formation of three political parties in the valley - Kashmiri Pandits Conference, Hindu Sabha in Jammu, and Sikhs' Shiromani Khalsa Darbar. This meant only non-Muslim groups were allowed political representation in the valley, leaving the majority of the population without an official political party.

That very same year saw several Muslim agitations that developed in reaction to the state's oppression. But the simmering tensions come to a boil on July 13, when a crowd of thousands tried to break into the Srinagar jail during the court hearing of a sedition case filed against a young Muslim man named Abdul Qadeer. Police responded with extreme brutality and 22 protesters were killed. As scholar and activist Prem Nath Bazaz noted, the sentiments of the crowd that rushed the prison were not anti-Hindu but anti-tyranny. Yet, the riots that took place in the aftermath of July 13 took a religious turn when shops owned by the Hindus were looted in the valley.

Bazaz attributed this to the shortsighted and inexperienced politics of the Reading Room Party as well as the hostile and discriminatory attitude of the Hindus towards the Muslim majority. Ever since that episode, however, all stakeholders in the Kashmir conflict have been attempting to communalise Kashmiri history. The struggle of the valley's working-class Muslims has been reduced to their religious identity, as if the religion that they follow makes their anger somewhat illegitimate.

While the suffering of the Muslim working class was immense under the Dogra rule, their situation did not get any better following Britain's departure from the Indian subcontinent and partition of colonial India into two nation-states.

Under the partition plan provided by the Indian Independence Act, Kashmir was given the options to become independent or accede to India or Pakistan.

The Dogra ruler at the time, Hari Singh, initially wanted Kashmir to become independent. But when tribesmen from Pakistan attempted to invade the region he agreed to join India in October 1947.

India's first Prime Minister Jawahar Lal Nehru sent troops to protect Kashmir from a possible Pakistani invasion. As a result, Hari Singh signed an instrument to accede the state to the Indian dominion. Article 370, which guaranteed Kashmir's autonomy in the Indian Union, was also added to the Indian constitution as a direct outcome of the instrument.

Unfortunately, it became clear in the following decades that India had no intention of protecting Kashmir's autonomy as in no time it started to act like yet another occupying imperial force and resumed the oppression of the region's long-suffering Muslim population.

At first, Nehru (a Kashmiri himself) appeared sympathetic to the cause of the Kashmiris. He promised multiple times to hold a plebiscite to determine the faith of Jammu and Kashmir. Back then, even the emergence of an independent Kashmir was being considered as a possible outcome.

Decades have passed, however, and the plebiscite Nehru promised was never held. Pakistan and India occasionally raised the issue and accused the other side of preventing the holding of a vote. To the convenience of both the states, the issue of plebiscite was eventually forgotten.

Since October 1947, India and Pakistan fought multiple wars over Kashmir, both claiming to have the best interests of the local population in mind. But they jointly suppressed Kashmiri voices that criticise the actions of both countries and demand independence.

One such example was the case of Maqbool Bhat, one of the founder members of Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front and proponent of organised armed struggle for the liberation of Kashmir. He was hunted down and hung by the Indian state, but the state of Pakistan also caused every trouble they could to stop Maqbool from organising a liberation movement for Kashmir that does not aim to pull the region into Pakistan's zone of influence.

Over the years, India and Pakistan did everything they could to control the narratives of Kashmir. India not only resorted to brutal methods of oppression, such as physical violence, torture, fake encounters, rape and unlawful prosecutions, it also concocted an alternative history, twisting data and facts to turn Indian public opinion against the plight of Kashmiri Muslims. Meanwhile, Pakistan was no innocent supporter of the Kashmiri struggle, as one of its former Presidents, Pervez Musharraf, openly admitted that the state supported and trained armed groups active in the valley, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), in the 1990s.

Despite the best efforts of the imperialist forces to silence and subdue them, the Kashmiris have been fighting for self-determination for hundreds of years. Today, imperial efforts to control the valley continue albeit quite ironically in the garb of nationalism. India's decision to revoke Jammu and Kashmir's special status thus is nothing other than yet another act of shameless imperialist aggression.

At worst, August 5, 2019, will be remembered by future generations as just another chapter in Kashmir's long history of imperial oppression. At best, this latest attack on the dignity of a long-suffering people will mark the beginning of an era of unprecedented resistance and struggle towards freedom for the Kashmiris.

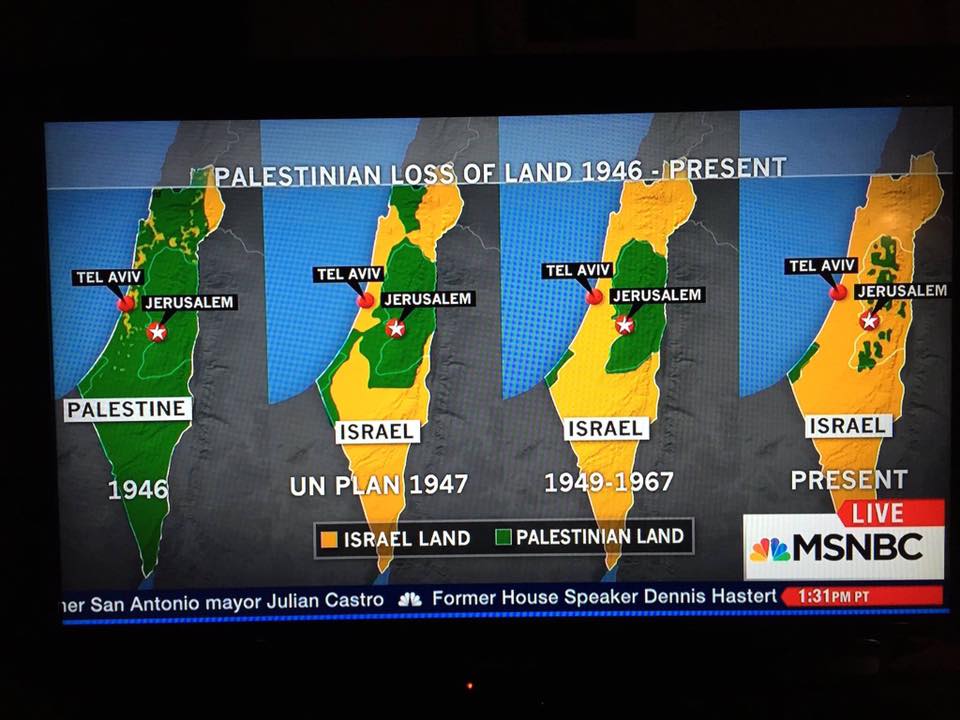

PALESTINA

Democracy Now: What is Israel trying to hide?

Unfortunately, US congresswoman Rashida Tlaib has said she will no longer visit the occupied West Bank under the "oppressive conditions" required by the Israeli government, who hours earlier said they would allow her entry on "humanitarian" grounds.

Tlaib, who is of Palestinian origin, tweeted her decision on Friday, a day after the Israeli government barred her and her fellow congresswoman Ilhan Omar from entering over their support of a boycott movement seeking to pressure Israel to end its rights abuses against Palestinians.

"When I won, it gave the Palestinian people hope that someone will finally speak the truth about the inhumane conditions. I can't allow the State of Israel to take away that light by humiliating me and use my love for my sity [grandma] to bow down to their oppressive and racist policies," she also tweeted.

The US-born Tlaib, 43, has roots in the Palestinian village of Beit Ur al-Fauqa in the occupied West Bank. Her grandmother and extended family still live in the village.

Unfortunately, US congresswoman Rashida Tlaib has said she will no longer visit the occupied West Bank under the "oppressive conditions" required by the Israeli government, who hours earlier said they would allow her entry on "humanitarian" grounds.

Tlaib, who is of Palestinian origin, tweeted her decision on Friday, a day after the Israeli government barred her and her fellow congresswoman Ilhan Omar from entering over their support of a boycott movement seeking to pressure Israel to end its rights abuses against Palestinians.

"When I won, it gave the Palestinian people hope that someone will finally speak the truth about the inhumane conditions. I can't allow the State of Israel to take away that light by humiliating me and use my love for my sity [grandma] to bow down to their oppressive and racist policies," she also tweeted.

The US-born Tlaib, 43, has roots in the Palestinian village of Beit Ur al-Fauqa in the occupied West Bank. Her grandmother and extended family still live in the village.

BRASIL

AOS FATOS:Todas as declarações de Bolsonaro, checadas

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário