BREAKING THE SILENCE

A moda dos seriados e séries abriu espaço para Israel praticar sua hasbara (propaganda) de maneira subliminar.

A primeira série a ser adaptada nos Estados Unidos foi BeTipul. Adaptada em vários países, inclusive o Brasil (Sessões de Terapia), ficou famosa com a adaptação hollywoodiana In Treatment, com o ator irlandês Gabriel Byrne no papel do psiquiatra. Foi um sucesso que abriu portas para as outras séries, politizadas.

A primeira desta leva foi Hatufim, que conta o retorno de três soldados israelenses capturados no Líbano e presos na Síria. Teve duas temporadas em Israel. Nos EUA virou o produto Homeland, interminável.

Depois veio Bnei Aruba, cujas duas temporadas contaram o sequestro da família de uma cirurgiã para que ela mate o primeiro ministro durante uma cirurgia de rotina. Nos EUA virou Hostages. Quem assistiu sabe do se trata e como julgar o conteúdo.

Até então, o Ocidente assistia às adaptações. Com raríssimas exceções como na Channel 4 britânica.

A Netflix começou a divulgar as séries originais há pouco tempo.

Mossad 101 (sobre o serviço secreto israelense) foi a primeira e depois Kfulim, rebatizada em inglês False Flag. "Inspirada" no assassinato do palestino Mahmoud al-Mabhouh em Dubai, pelo Mossad, em 2010. Transformado em uma fantasia que protagoniza o ShinBet, serviço secreto que opera em Israel e nos territórios palestinos ocupados cusando muitos danos aos palestinos no quotidiano. Mas isso não é mostrado. Como os seriados dos EUA que só mostram o "heroísmo" dos agentes da CIA que é uma agência que semeia guerras e desastres mundo afora.

Há outros seriados, mas o que me ocupa hoje é Fauda, cuja segunda temporada foi há pouco divulgada. A primeira fez sucesso até na Palestina, pois foi a primeira vez que um produto televisivo israelense retratava os palestinos como seres humanos de carne e osso como os ocupantes. Foi por isso que seus criadores, Avi Issacharoff e Lior Raz, reservistas da unidade militar dramatizada, tiveram dificuldades de encontrar patrocinadores e produtores. No início. Agora chovem, pois an segunda temporada a propaganda é menos subliminar, os israelenses são super-valorizados e os palestinos sofrem o tratamento inverso, na maior sutileza.

Mas o mais importante é a série conseguir mostrar a Cisjordânia sem muros, sem checkpoints, sem colonos violentos, sem apartheid. Enfim, a série pinta o retrato de uma ocupação idílica surreal. O pior é que muita gente - jovens e adultos desinformados que veem o mundo através da telinha e do telão de seus televisores ou de seus monitores - acreditam, e acabam simpatizando com os israelenses, através dos atores e do bom roteiro que os prende na poltrona do início ao fim.

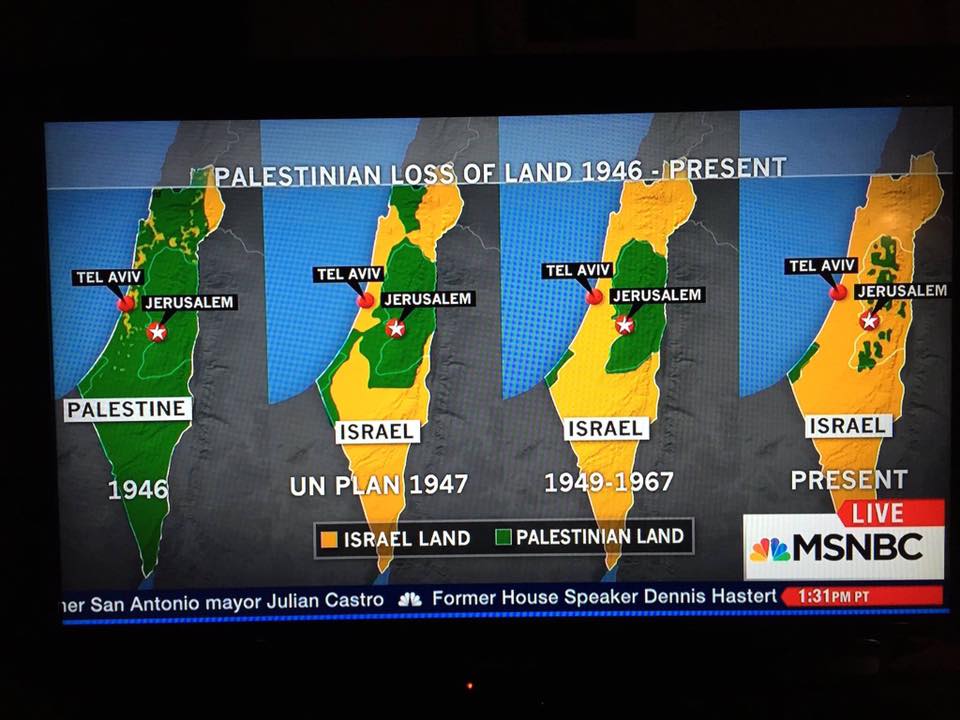

Portanto, aviso aos navegantes, naveguem pelos seriados israelenses atentos. Não se deixem enganar pela hasbara e nem aliciar pelo "heroísmo" dos protagonistas israelenses que são, na realidade, ocupantes, repressores e opressores de um povo do qual tomaram as terras em 1948 e continuam a tomar hoje, assim como suas vidas e perspectiva de futuro e cidadania.

Israel’s biggest hit series returns to our screens this week, opening with Israel’s biggest nightmare. The second series of Fauda, the political thriller about an Israeli army undercover unit, begins with a bomb explosion at a bus stop. But it gets worse, as it turns out the attack wasn’t ordered by Hamas, but by a new menace – a returnee from Syria who has been training with Islamic State.

That’s how we’re plunged back into Fauda, Arabic for “chaos”, Israel’s international Netflix hit, which the streaming service picked up in 2016. Released on 24 May, the series returns with its tight, testy unit of Arabic-speaking Israeli special force infiltrators who work undercover in the Palestinian West Bank to track and kill wanted terrorists.

That’s how we’re plunged back into Fauda, Arabic for “chaos”, Israel’s international Netflix hit, which the streaming service picked up in 2016. Released on 24 May, the series returns with its tight, testy unit of Arabic-speaking Israeli special force infiltrators who work undercover in the Palestinian West Bank to track and kill wanted terrorists.

It’s mostly in Arabic and Hebrew, but that hasn’t limited the appeal. Netflix, which has 109 million members across 190 countries, describes it as a global phenomenon – one of a string of Israeli successes. Netflix has already commissioned a third series along with other shows from Fauda’s creators, journalist Avi Issacharoff and Lior Raz, who served in the undercover unit on which the series is based and plays its predictably gruff Israeli lead Doron Kavillio.

Fauda is frequently credited with evenhandedness over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and attempts to humanise Palestinian terror operatives. But that’s in the eye of the beholder, and certainly less true of this second series. For an Israeli Jewish audience, Fauda does break new ground. “It’s the first TV series that showed the Palestinian narrative in a way that you can actually feel something for someone who acts like a terrorist,” says Itay Stern at Israel’s Haaretz newspaper. “You can understand the motives and the emotion and that’s unique, because until that point you couldn’t really see it on TV.”

At a time when Israelis rarely seek out Palestinian viewpoints in real life, much less on TV, this may explain why Fauda’s creators initially struggled to find a domestic outlet for the series. It portrays the infiltrator unit, whose members (mostly male, but there is one woman) kill, torture, assault and violently threaten Palestinians in a manner that jars with any claims of moral superiority. And this second series contains more narrative mirroring. We see each side struggle with unity and discipline over revenge and going rogue, with causes taking precedence over family relationships, lured into a violence that creates its own momentum. Both sides are compromised, manipulative and varying degrees of unhinged.

But none of that gets away from it being overwhelmingly narrated from an Israeli viewpoint, focused on the Israeli protagonists. More so than in the first series, the Israeli occupation is nowhere to be seen – there’s no wall, no settlements or settlers, no house demolitions, only a few small checkpoints and none of the everyday brutalities of life under occupation. Yes, it shows that Palestinians love their mothers, but it also renders them as violent fanatics without a political cause.

Fauda’s creators have said they want to show that everyone living in a war zone pays a price, but such portrayals of an equality of suffering are ripe for criticism in the midst of an asymmetric conflict, in which one side is under occupation. This is more acutely obvious at a time when international media has focused on Israel opening fire on unarmed protesters near the Gaza border earlier this month, killing 62 Palestinians, including children, and wounding over 1,000 in a single day.

So I must point to another problem with Fauda. If you’re not careful, you find yourself drawn into the assassinations, you get lured into the cat and mouse, as the series essentially depicts targeted killings. The concept of right and wrong gets erased, the illegality gets erased … It just becomes this action-packed show.

This kind of blurring brings to mind US war-on-terror films such as Zero Dark Thirty, with its depiction of Osama bin Laden’s capture serving as a PR exercise for the use of torture during interrogations. Meanwhile, Fauda’s Isis storyline stretches credibility, at the same time feeding the worst stereotypes. “It’s a bit lazy. Isis is not really active in Gaza or the West Bank,” says Stern. Diana Buttu, a Palestinian-Canadian human rights lawyer and former spokeswoman for the Palestinian Liberation Organisation says that the effect is to reinforce the absence of a Palestinian cause. “We don’t have any legitimate grievances. It’s all Islamic-driven,” she says, noting that it “turns Palestinians into irrational figures who want only to kill Israelis”.

Claims by Raz that writing the series was his real therapy, after suffering with PTSD, help locate Fauda in an Israeli genre dubbed “shooting and crying” – laments over the effect of wars on the morality and sanity of Israelis fighting them. But Fauda is different. Let’s call it “viewing while cursing”, into which category we can also place the US hit series Homeland.

Both dramas rely on protagonists entrusted with critical jobs despite routinely reckless behaviour. Both test your patience. In the case of Fauda, it’s not just the politics but also the relentless machismo; midway into the second series it feels like watching interchangeable rooms full of men in guns and distressed denim, each at some point telling a female character: “Don’t worry, I’ll get us out of here.”

Yet both shows get you binge-watching, despite irritating plot holes, political sanctimony and misrepresentations of Muslims or Palestinians. It’s a bit like speed-reading a cheap thriller, ignoring the bad dialogue and badly drawn characters, along with the mounting self-loathing over the time you’re squandering, just for the sugar rush of the story’s end.

Fauda is frequently credited with evenhandedness over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and attempts to humanise Palestinian terror operatives. But that’s in the eye of the beholder, and certainly less true of this second series. For an Israeli Jewish audience, Fauda does break new ground. “It’s the first TV series that showed the Palestinian narrative in a way that you can actually feel something for someone who acts like a terrorist,” says Itay Stern at Israel’s Haaretz newspaper. “You can understand the motives and the emotion and that’s unique, because until that point you couldn’t really see it on TV.”

At a time when Israelis rarely seek out Palestinian viewpoints in real life, much less on TV, this may explain why Fauda’s creators initially struggled to find a domestic outlet for the series. It portrays the infiltrator unit, whose members (mostly male, but there is one woman) kill, torture, assault and violently threaten Palestinians in a manner that jars with any claims of moral superiority. And this second series contains more narrative mirroring. We see each side struggle with unity and discipline over revenge and going rogue, with causes taking precedence over family relationships, lured into a violence that creates its own momentum. Both sides are compromised, manipulative and varying degrees of unhinged.

But none of that gets away from it being overwhelmingly narrated from an Israeli viewpoint, focused on the Israeli protagonists. More so than in the first series, the Israeli occupation is nowhere to be seen – there’s no wall, no settlements or settlers, no house demolitions, only a few small checkpoints and none of the everyday brutalities of life under occupation. Yes, it shows that Palestinians love their mothers, but it also renders them as violent fanatics without a political cause.

Fauda’s creators have said they want to show that everyone living in a war zone pays a price, but such portrayals of an equality of suffering are ripe for criticism in the midst of an asymmetric conflict, in which one side is under occupation. This is more acutely obvious at a time when international media has focused on Israel opening fire on unarmed protesters near the Gaza border earlier this month, killing 62 Palestinians, including children, and wounding over 1,000 in a single day.

So I must point to another problem with Fauda. If you’re not careful, you find yourself drawn into the assassinations, you get lured into the cat and mouse, as the series essentially depicts targeted killings. The concept of right and wrong gets erased, the illegality gets erased … It just becomes this action-packed show.

This kind of blurring brings to mind US war-on-terror films such as Zero Dark Thirty, with its depiction of Osama bin Laden’s capture serving as a PR exercise for the use of torture during interrogations. Meanwhile, Fauda’s Isis storyline stretches credibility, at the same time feeding the worst stereotypes. “It’s a bit lazy. Isis is not really active in Gaza or the West Bank,” says Stern. Diana Buttu, a Palestinian-Canadian human rights lawyer and former spokeswoman for the Palestinian Liberation Organisation says that the effect is to reinforce the absence of a Palestinian cause. “We don’t have any legitimate grievances. It’s all Islamic-driven,” she says, noting that it “turns Palestinians into irrational figures who want only to kill Israelis”.

Claims by Raz that writing the series was his real therapy, after suffering with PTSD, help locate Fauda in an Israeli genre dubbed “shooting and crying” – laments over the effect of wars on the morality and sanity of Israelis fighting them. But Fauda is different. Let’s call it “viewing while cursing”, into which category we can also place the US hit series Homeland.

Both dramas rely on protagonists entrusted with critical jobs despite routinely reckless behaviour. Both test your patience. In the case of Fauda, it’s not just the politics but also the relentless machismo; midway into the second series it feels like watching interchangeable rooms full of men in guns and distressed denim, each at some point telling a female character: “Don’t worry, I’ll get us out of here.”

Yet both shows get you binge-watching, despite irritating plot holes, political sanctimony and misrepresentations of Muslims or Palestinians. It’s a bit like speed-reading a cheap thriller, ignoring the bad dialogue and badly drawn characters, along with the mounting self-loathing over the time you’re squandering, just for the sugar rush of the story’s end.

Small wonder, then, that all eyes are on finding the new Homeland, itself based on an Israeli TV series, Hatufim. And it’s not surprising that the quest is focused on Israel, which has spawned a string of international hits, starting with In Treatment, a 2008 HBO adaptation of the Hebrew-language Be Tipul. In 2016 Neflix started airing Mossad 101, about Israel’s intelligence service, while earlier this year Hulu nabbed False Flag, a conspiracy thriller loosely premised on the 2010 assassination of Hamas official Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in Dubai, widely believed to be the work of the Mossad, by a hit squad carrying foreign passports.

HBO bought The Oslo Diaries this year, covering the secret negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians that led to the 1993 peace process agreements. And last month, the Israeli drama When Heroes Fly took best series at the inaugural TV festival at Cannes, for its depiction of another Israeli commando unit, this time set partly in Colombia. In March, the Israeli media company Keshet International launched a $55m (£41m) fund for drama, hoping to create the next Homeland.

Similarities are drawn with Denmark, home of addictive global hits The Killing, Borgen and The Bridge – another country whose tiny domestic market has concentrated creative energies on producing internationally relatable stories. According to Itay Harlap, author of Television Drama in Israel: Identities in Post-TV Culture, the country’s successes are down to on-demand and satellite formats loosening the constraints of terrestrial TV: “It was difficult to find radical TV shows in broadcasting, because of concerns over advertising and offending people ideologically.” Now, series-makers are after buzz rather than ratings, knowing they can explore new ideas and sell overseas. “It’s quite amazing that the government is going in one direction and TV series are going in another."

Not really. That is the problem. The series are made to give a heroic impression of a military rogue state and whitewash its daily crimes.

HBO bought The Oslo Diaries this year, covering the secret negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians that led to the 1993 peace process agreements. And last month, the Israeli drama When Heroes Fly took best series at the inaugural TV festival at Cannes, for its depiction of another Israeli commando unit, this time set partly in Colombia. In March, the Israeli media company Keshet International launched a $55m (£41m) fund for drama, hoping to create the next Homeland.

Similarities are drawn with Denmark, home of addictive global hits The Killing, Borgen and The Bridge – another country whose tiny domestic market has concentrated creative energies on producing internationally relatable stories. According to Itay Harlap, author of Television Drama in Israel: Identities in Post-TV Culture, the country’s successes are down to on-demand and satellite formats loosening the constraints of terrestrial TV: “It was difficult to find radical TV shows in broadcasting, because of concerns over advertising and offending people ideologically.” Now, series-makers are after buzz rather than ratings, knowing they can explore new ideas and sell overseas. “It’s quite amazing that the government is going in one direction and TV series are going in another."

Not really. That is the problem. The series are made to give a heroic impression of a military rogue state and whitewash its daily crimes.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário