Israeli occupation forces killed four Palestinians, including a child, and injured hundreds more on the 11th consecutive Friday of Great March of Return rallies in Gaza.

At least four others remained in critical condition on Friday night, according to the health Ministry.

This Friday, as they have before, Israeli forces fired live ammunition, rubber-coated metal bullets and tear gas at Palestinians gathered in areas near Gaza’s eastern boundary with Israel to demand an end to the Israeli siege of the territory and the right of return to lands from which they were expelled.

Israeli forces injured almost 300 people, more than 130 with live ammunition, according to human rights group Al Mezan.

Haitham Muhammad Khalil al-Jamal, 14, was fatally shot in the stomach east of his hometown of Rafah in southern Gaza and later died of his injuries in a local hospital.

He is the 15th Palestinian child killed in Gaza by Israeli occupation forces since the beginning of the protests on 30 March.

In that period, Israeli forces have killed more than 130 Palestinians, including over 100 during protests. Almost 4,000 have been injured with live ammunition.

Despite all Israeli visible crimes and determination to Ethnic cleanse Palestine, a Gallup poll of March, 2018 about opinions of the Israeli-Palestinian "conflict" revealed that 64% of US citizens sympathize more with Israel, while 19% view the Palestinians more favorably. I would'nt be surprised if it was the same for America and Europe. The fact that the root cause of the conflict is the expulsion of the indigenous population and consequent seizure of much of Palestine by a foreign people seems to be lost on the American public at large. Much of the opinion is a direct result of the generally one-sided coverage of the conflict by the mainstream media.

The coverage of the events of May 14, when the Israeli army killed sixty Palestinians and injured thousands more in Gaza during the Great March of Return, provides a depressing snapshot of the Western media’s treatment of the conflict.

I will focus here on a recent article in the Economist, the British current affairs magazine that has a wide circulation worldwide. It is considered to be conservative economically but liberal politically. The Economist’s article employs many of the tools used by the mainstream media when discussing the conflict. It repeats and accepts as fact Israeli and Western talking points about the conflict without analysis; it uses loaded terminology; it chooses which aspects of the events to focus on in order to present its biased point of view; it almost entirely ignores the larger context in which they have taken place.

The cover of the May 19 – May 24 issue of the Economist depicts a Palestinian boy with a slingshot that is presumably aimed at Israeli soldiers. This choice in itself is already an indicator of the magazine’s slant. Rather than focus on the shooting and killing of mostly unarmed civilians protesting against the inhumane and illegal blockade of Gaza, the editor fixates on the fact that the Palestinians were throwing rocks. It was their fault, the image seems to indicate, not that of the snipers. A reasonable analogy is the beating of a small, helpless child by a large, strong man. The child kicks at him desperately to get away. Should one focus on the child kicking the man or on the man beating the child? The Economist has made its choice clear.

This is only reinforced by the headline. “Gaza, there is a better way,” it reads. The subtitle is “Israel is answerable for this week’s deaths in Gaza. But it is time for Palestinians to take up non-violence.” This is the thrust of the article. Palestinians should take the moral high ground by marching peacefully rather than engaging in violence. A Western observer advising a non-Western people how to conduct its business smacks of the paternalism exhibited by colonialists over the centuries, and it is extremely offensive. The content of the statement—even if we ignore its patronizing tone—is absurd. The notion that the Palestinians are being violent by slinging rocks and throwing Molotov cocktails at the 4thmost powerful army in the world is misleading and lacks context. Don’t kick the man, the magazine seems to be telling the child being beaten. You don’t want to be violent.

There are many problematic statements made by the author of the article. I will discuss a few of them below.

“…when rockets or other attacks provoke a fully-fledged war…” In this sentence the author places the blame for the events of May 14, as well as the three recent major Israeli assaults on Gaza, squarely on the shoulders of Hamas. He is repeating Israeli talking points without questioning them. By using the term “war,” he is absolving Israel of any responsibility for the killing of the protestors. After all, it is somewhat acceptable for soldiers to get killed in war. It is much less so, if unarmed protestors are being murdered. But this is not a war. That term connotes a conflict between two more or less equal parties, and in this case, it is extremely misleading. One would never refer to the Holocaust as a war between Nazis and Jews or the eradication of the Native Americans as a war between them and the Europeans.

The mainstream media has largely accepted the Israeli view that the assaults on Gaza—in 2008/2009, 2012 and 2014—were provoked by Hamas’ rocket attacks. But this is false or—at best—highly debatable. Journalist Ben White has studied this question carefully in his book, The 2014 Gaza War: 21 Questions and Answers, and concludes that Hamas’ rocket attacks had little to do with the Israeli assaults.

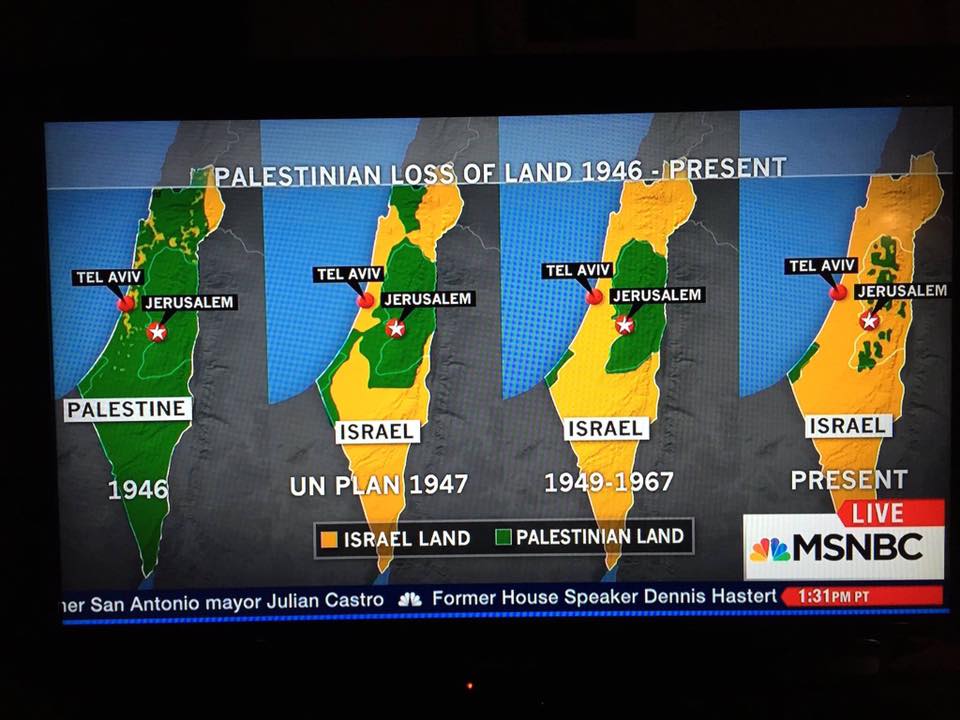

“…threatening to “return” to the lands their forefathers lost when Israel was created…” This is the only mention of the Nakba in the entire article, and the Nakba of course represents the reason for the conflict in the first place. Omitting it is analogous to not mention the beating of the child at all, only saying that a child is kicking a man. Moreover, the Palestinians did not “lose” their land, and implying so is revising history. Their land was taken from them by Zionist forces, who expelled roughly three-quarters of a million Palestinians in order to make room for a Jewish homeland.

“…Israel’s army may well have used excessive force. But…” This is the closest the author comes to condemning the Israeli actions on May 14. Following the “but” is a list excusing these actions. The statement above should be made without qualification. Of course excessive force was used. Thousands of Palestinians were injured, while—according to reports—a single Israeli soldier was lightly wounded when he was struck by a stone.

“…Israel as a thriving democracy…” Israel’s claim to be the only democracy in the Middle East is generally accepted by the mainstream media in the West without question. But is it true? Certainly any country that withholds rights from one-fifth of its citizens because of their religious identity cannot be considered a full democracy. Indeed, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index for 2017, Israel is classified as a flawed democracy. Its level of democracy is ranked #30 in the world, tied with Estonia. It scores very well in several categories, such as its electoral process and level of political participation, but when it comes to civil liberties, which include human rights and religious tolerance, it is ranked #86 in the world, tied with, among others, Uganda, Malawi and Tunisia. It is of course difficult to compare countries with entirely different cultures and histories, but nevertheless Israel would probably not be happy to be mentioned in the same breath as Uganda when it comes to democracy.

Although it is not stated explicitly, it is likely that Israel’s scores in the Democracy Index are based only on what it does in Israel proper, and not in the West Bank and Gaza. After all, since none of the millions of Palestinians residing therein are allowed to vote, a high score in the category of political participation would be impossible. Since Israel does have nearly complete control in the Occupied Territories, its abominable human rights record there should be taken into account, which would significantly lower its democracy score.

“Many hands are guilty for this tragedy.” The tragedy here is a reference to the dire humanitarian situation in Gaza, which the United Nations reports will be uninhabitable by the year 2020. The author blames Israel, Egypt, Fatah and Hamas. He neglects to mention that Israel, as the occupying power, bears primary responsibility. Indeed, as legal scholar Noura Erakat explains, “as the occupying power of the Gaza Strip… Israel has an obligation and a duty to protect the civilians under its occupation.” This includes neither using mathematical formulas to keep them on the brink of starvation, nor shooting and killing them indiscriminately. For those who argue that the Israeli occupation of Gaza ended in 2005, Erakat counters that “Israel maintains control of the territory’s air space, territorial waters, electromagnetic sphere, population registry and the movement of all goods and people.” This constitutes a de-facto occupation.

“[Hamas] destroyed the Oslo peace accords through its campaign of suicide bombings in the 1990s and 2000s.” Not really. It is largely Israeli settlement policy that is to blame for their failure, as argued by prominent Israeli historian Avi Shlaim. Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud government came to power after the assassination of Yitzak Rabin, one of the architects of the accords, and did everything it could to undermine them. The Oslo Accords, although they did not explicitly mention so, were intended to lead to the eventual creation of a Palestinian state. By increasing the rate of settlement expansion in the West Bank, Netanyahu ensured that such a state would never come to be. By 2000, Oslo was all but dead.

“[Hamas] stores its weapons in civilian sites, including mosques and schools, making them targets.” There is no evidence for this, as stated by Erakat. During the 2014 assault, Hamas did store weapons in two United Nations schools, which were empty at the time.

“[Hamas] refuses to fully embrace a two-state solution… If it accepted Israel’s right to exist…” Hamas’ charter does state that it refuses to accept Israel’s existence. However, scholar Noam Chomsky argues that Hamas long ago renounced this charter, while Hamas does offer de-facto recognition of Israel, since it was willing to enter a unity government with the Palestinian Authority (PA), an action that implies acceptance of all previous PA-Israel agreements. What Zionists often neglect to mention is that it is Netanyahu’s ruling Likud party that refuses to accept the notion of a Palestinian state, not merely by its actions, but in an official platform, which includes the statement: The Government of Israel flatly rejects the establishmentof a Palestinian/Arab state west of the Jordan River. Since each party refuses to accept the other, why does the Economist only mention Hamas?

The statements from the article referred to above effectively show the magazine’s bias, but even more revealing are the omissions. No mention is made of the fact that the dead include children, medics and journalists. Would the author be forced to conclude that Israel did, in fact, use excessive force, if he/she had to confront the fact that clearly innocent people were killed? Why is none of the witness testimony available to us about the details of some of the shootings included? In fact, there is little discussion about the victims at all. It is all about Hamas, which is what Israel wants you to think. In reality, Hamas had little to do with the protest.

On a larger scale, there is no mention of the Nakba, the Right of Return or the Occupation, which—as even a beginning history student would tell you—are crucial elements both in the larger conflict and in the events of May 14. By omitting them, the Economist is able to reinforce the Israeli and American version of events without making even a token attempt at providing a balanced point of view.

In the West Bank the Palestinians are humiliated daily in their big cage made of checkpoints and Jewish colonies

June 5, 2018 marked the 51st anniversary of the Israeli Occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza.

But, unlike the massive popular mobilization that preceded the anniversary of the Nakba – the catastrophic destruction of Palestine in 1948 – on May 15 and the Following Fridays Great March of Return, the anniversary of the Occupation is hardly generating equal mobilization.

The unsurprising death of the ‘peace process’ and the inevitable demise of the ‘two-state solution’ has shifted the focus from ending the Occupation per se, to the larger and more encompassing problem of Israel’s colonialism throughout Palestine.

The grassroot mobilization in Gaza and the West Bank, and among Palestinian Bedouin communities in the Naqab Desert are, once more, widening the Palestinian people’s sense of national aspirations. Thanks to the limited vision of the Palestinian leadership, those aspirations have, for decades, been confined to Gaza and West Bank.

In some sense, the ‘Israeli Occupation’ is no longer an occupation as per international standards and definitions. It is merely a phase of Zionist colonization of historic Palestine, a process that began over a 100 years ago, and carries on to this date.

“The law of occupation is primarily motivated by humanitarian consideration; it is solely the facts on the ground that determine its application,” states the International Committee of the Red Cross website.

It is for practical purposes that we often utilize the term ‘occupation’ with reference to Israel’s colonization of Palestinian land, occupied after June 5, 1967. The term allows for the constant emphasis on humanitarian rules that are meant to govern Israel’s behavior as the Occupying Power.

However, Israel has already, and repeatedly, violated most conditions of what constitute an ‘Occupation’ from an international law perspective, as articulated in the 1907 Hague Regulations (articles 42-56) and the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.

According to these definitions, an ‘Occupation’ is a provisional phase, a temporary situation that is meant to end with the implementation of international law regarding that particular situation.

‘Military occupation’ is not the sovereignty of the Occupier over the Occupied; it cannot include transfer of citizens from the territories of the Occupying Power to Occupied land; it cannot include ethnic cleansing; destruction of properties; collective punishment and annexation.

It is often argued that Israel is an Occupier that has violated the rules of Occupation as stated in international law.

This would have been the case a year, two or five years after the original Occupation had taken place, but not 51 years later. Since then, the Occupation has turned into long-term colonization.

An obvious proof is Israel’s annexation of Occupied land, including the Syrian Golan Heights and Palestinian East Jerusalem in 1981. That decision had no regard for international law, humanitarian or any other.

Israeli politicians have, for years, openly debated the annexation of the West Bank, especially areas that are populated with illegal Jewish settlements, which are built contrary to international law.

Those hundreds of settlements that Israel has been building in the West Bank and East Jerusalem are not meant as temporary structures.

Dividing the West Bank into three zones, areas A, B and C, each governed according to different political diktats and military roles, have little precedent in international law.

Israel argues that, contrary to international law, it is no longer an Occupying Power in Gaza; however, an Israel land, maritime and aerial siege has been imposed on the Strip for over 11 years. With successive Israeli wars that have killed thousands, to a hermetic blockade that has pushed the Palestinian population to the brink of starvation, Gaza subsists in isolation.

Gaza is an ‘Occupied Territory’ by name only, without any of the humanitarian rules applied. In the last 10 weeks alone, over 120 unarmed protesters, journalists and medics were killed and 13,000 wounded, yet the international community and law remain inept, unable to face or challenge Israeli leaders or to overpower equally cold-hearted American vetoes.

The Palestinian Occupied Territories have, long ago, crossed the line from being Occupied to being colonized. But there are reasons that we are trapped in old definitions, leading amongst them is American political hegemony over the legal and political discourses pertaining to Palestine.

One of the main political and legal achievements of the Israeli war – which was carried out with full US support – on several Arab countries in June 1967 is the redefining of the legal and political language on Palestine.

Prior to that war, the discussion was mostly dominated by such urgent issues as the ‘Right of Return’ for Palestinian refugees to go back to their homes and properties in historic Palestine.

The June war shifted the balances of power completely, and cemented America’s role as Israel’s main backer on the international stage.

Several UN Security Council resolutions were passed to delegitimize the Israeli Occupation: UNSCR 242, UNSCR 338 and the less talked about but equally significant UNSCR 497.

242 of 1967 demanded “withdrawal of Israel armed forces” from the territories it occupied in the June war. 338, which followed the war of 1973, accentuated and clarified that demand. Resolution 497 of 1981 was a response to Israel’s annexation of the Golan Heights. It rendered such a move “null and void and without international and legal affect.”

The same applied to the annexation of Jerusalem as to any colonial constructions or any Israeli attempts aimed at changing the legal status of the West Bank.

But Israel is operating with an entirely different mindset.

Considering that anywhere between 600,000 to 750,000 Israeli Jews now live in the ‘Occupied Territories’, and that the largest settlement of Modi’in Illit houses more than 64,000 Israeli Jews, one has to wonder what form of military occupation blue-print Israel is implementing, anyway?

Israel is a settler colonial project, which began when the Zionist movement aspired to build an exclusive homeland for Jews in Palestine, at the expense of the native inhabitants of that land in the late 19th century.

Nothing has changed since. Only facades, legal definitions and political discourses. The truth is that Palestinians continue to suffer the consequences of Zionist colonialism and they will continue to carry that burden until that original sin is boldly confronted and justly remedied.

PALESTINA

Israeli checkpoints in Palestine

Israeli danser Ohad Naharin reads an IDF soldier's testimony