"The truth", noted Oscar Wilde, "is rarely pure and never simple".

Yet, the point remains: US President Donald Trump, not dissimilarly from Arthur Balfour one century ago, is imposing a unilateral understanding of the local reality without knowing much of its complex past and present. To pay the price for this will be, once again, Israelis and Palestinians alike.

US President Donald Trum has said it is time to officially recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Arthur Balfour, who gave his name to the 1917 Declaration, visited Palestine for the first time in his life in 1925. On that occasion, he presided over the opening of Jerusalem's Hebrew University, accompanied by Chaim Weizmann and his wife, Vera.

Yet, the point remains: US President Donald Trump, not dissimilarly from Arthur Balfour one century ago, is imposing a unilateral understanding of the local reality without knowing much of its complex past and present. To pay the price for this will be, once again, Israelis and Palestinians alike.

US President Donald Trum has said it is time to officially recognise Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

Arthur Balfour, who gave his name to the 1917 Declaration, visited Palestine for the first time in his life in 1925. On that occasion, he presided over the opening of Jerusalem's Hebrew University, accompanied by Chaim Weizmann and his wife, Vera.

Despite Balfour's very limited knowledge of the local reality, his actions were based on the rock-solid conviction that the ideas that he was embracing were "rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land".

Each observer and historian can have a different opinion about these aspects and Balfour's approach.

Today Trump's unilateral decision is ill-fated. Despite growing absolutist claims, "Uru-Shalem" (the city "founded by Shalem", a god venerated by the Canaanites), founded by the Canaanites around 5,000 years ago, has not belonged to one single people in its entire history.

This is a further reason why, in its nature, Jerusalem must be internationally, or at least bilaterally, shared.

As to why to make the move now and not earlier or later, I believe there are three main reasons, none of which are mutually exclusive.

First, US domestic politics. Today’s announcement plays well with Trump’s base amongst right-wing Christian evangelicals, as well as with the likes of influential individuals like Sheldon Adelson. “Hallelujah!” proclaims alt-right site Breitbart’s main splash today, welcoming the news.

The fact that such constituencies are already committed to Trump does not rule out the fact that policy steps can be taken as a gift to the converted; Trump-ism has never been about building wide coalitions, or reaching out across various divides, but about energising and mobilising a base.

Don’t forget, of course, that a pledge to move the US embassy to Jerusalem was part of Trump’s election campaign; for a president who has struggled to fulfil his promises, a win is a win.

Second, Benjamin Netanyahu, along with other senior Israeli officials, might well have done a good job in persuading the Trump administration to make such a move – something that the likes of Jared Kushner, Jason Greenblatt and US envoy to Israel David Friedman would be personally amenable to anyway.

For Netanyahu – and this is already evident in remarks made this morning – such a shift in American policy fits nicely with his narrative about a confident, nationalistic Israel expanding its diplomatic ties, the warnings of international isolation from his political enemies shown to be hollow threats

Whether Trump’s decision on Jerusalem is actually in the best interests of Netanyahu, or his coalition, is a separate matter; but misguided or otherwise, Netanyahu would appear to have been urging the Trump administration to take such a step.

Third – and this is perhaps where many commentators are missing a trick – the Trump administration might well envisage, and justify, the Jerusalem shift in the context of its much-heralded efforts at securing the “deal of the century”.

At first glance this can seem counter-intuitive, since everyone from Jordan to the European Union has criticised the Jerusalem announcement as detrimental to efforts at advancing so-called Israeli-Palestinian “peace” and a “two-state solution”.

para

In fact, Trump is more likely to view, and present, the Jerusalem move as a gesture to Israel that will creat the expectancy of pressure for a corresponding "gesture" in retur, such as economic-focuses measures in the occupied West Bank.

Whether or not this calculation quite adds up, is another question – though Mahmoud Abbas and his team have, over the years, demonstrated a notable capacity for giving US efforts “one more chance”.

In other words, rather than being an inexplicable spanner in the works of the Trump administration’s wider efforts at birthing the “ultimate deal”, the White House – and perhaps Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman too – may well see the move as part and parcel of that very project (hence the weak response, thus far, from Riyadh).

On the ground, meanwhile, the reality for Palestinian residents of what is an apartheid city remains unchanged: home demolitions, municipal discrimination, brutal raids, and settler-driven displacement. This is Jerusalem’s grim reality that, by their long-standing inaction, Israel’s allies have played a crucial role in facilitating. Trump thus joins a crowded field of the complicit.

First, US domestic politics. Today’s announcement plays well with Trump’s base amongst right-wing Christian evangelicals, as well as with the likes of influential individuals like Sheldon Adelson. “Hallelujah!” proclaims alt-right site Breitbart’s main splash today, welcoming the news.

The fact that such constituencies are already committed to Trump does not rule out the fact that policy steps can be taken as a gift to the converted; Trump-ism has never been about building wide coalitions, or reaching out across various divides, but about energising and mobilising a base.

Don’t forget, of course, that a pledge to move the US embassy to Jerusalem was part of Trump’s election campaign; for a president who has struggled to fulfil his promises, a win is a win.

Second, Benjamin Netanyahu, along with other senior Israeli officials, might well have done a good job in persuading the Trump administration to make such a move – something that the likes of Jared Kushner, Jason Greenblatt and US envoy to Israel David Friedman would be personally amenable to anyway.

For Netanyahu – and this is already evident in remarks made this morning – such a shift in American policy fits nicely with his narrative about a confident, nationalistic Israel expanding its diplomatic ties, the warnings of international isolation from his political enemies shown to be hollow threats

Whether Trump’s decision on Jerusalem is actually in the best interests of Netanyahu, or his coalition, is a separate matter; but misguided or otherwise, Netanyahu would appear to have been urging the Trump administration to take such a step.

Third – and this is perhaps where many commentators are missing a trick – the Trump administration might well envisage, and justify, the Jerusalem shift in the context of its much-heralded efforts at securing the “deal of the century”.

At first glance this can seem counter-intuitive, since everyone from Jordan to the European Union has criticised the Jerusalem announcement as detrimental to efforts at advancing so-called Israeli-Palestinian “peace” and a “two-state solution”.

para

In fact, Trump is more likely to view, and present, the Jerusalem move as a gesture to Israel that will creat the expectancy of pressure for a corresponding "gesture" in retur, such as economic-focuses measures in the occupied West Bank.

Whether or not this calculation quite adds up, is another question – though Mahmoud Abbas and his team have, over the years, demonstrated a notable capacity for giving US efforts “one more chance”.

In other words, rather than being an inexplicable spanner in the works of the Trump administration’s wider efforts at birthing the “ultimate deal”, the White House – and perhaps Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman too – may well see the move as part and parcel of that very project (hence the weak response, thus far, from Riyadh).

On the ground, meanwhile, the reality for Palestinian residents of what is an apartheid city remains unchanged: home demolitions, municipal discrimination, brutal raids, and settler-driven displacement. This is Jerusalem’s grim reality that, by their long-standing inaction, Israel’s allies have played a crucial role in facilitating. Trump thus joins a crowded field of the complicit.

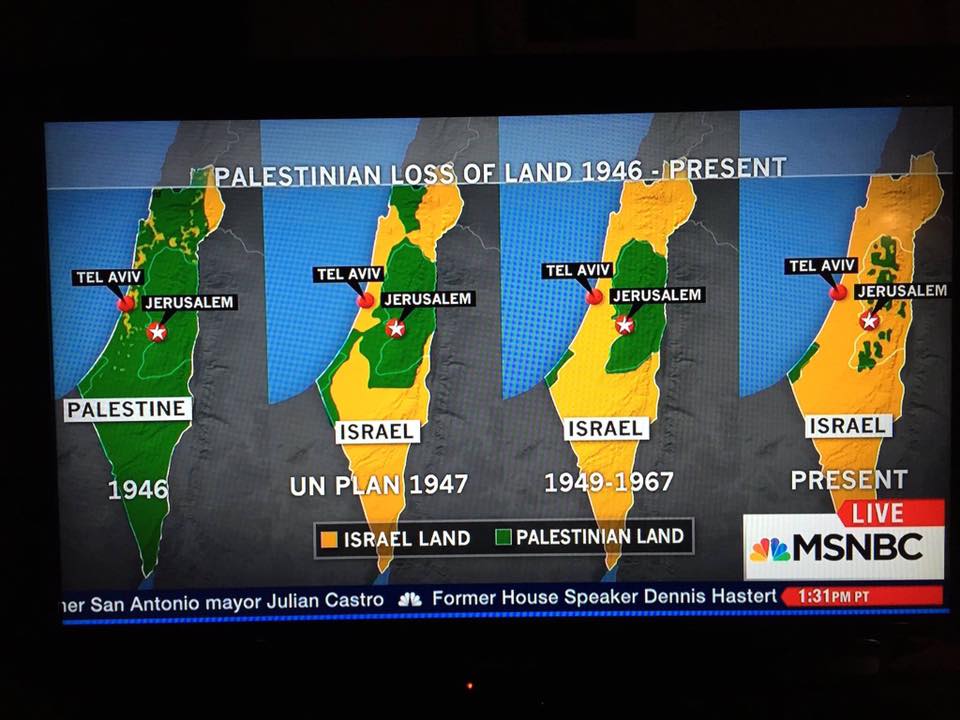

Before the creation of the State of Israel, the newly formed United Nations had, in 1947, voted on a partition plan to divide historical Palestine what was then British-Mandate Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states. Although that partition map put Jerusalem within the boundaries of the envisaged Palestinian Arab state, it designated Jerusalem and Bethlehem as corpus separatum, under international rule. The special status was decided on the basis of Jerusalem’s religious importance to all three Abrahamic faiths, as home to Al-Aqsa Mosque, Church of Holy Sepulchre, and the Western Wall of the Jewish temple built by Herod. There were also 100,000 Jews living in Jerusalem at the time, and the partition map envisaged an equivalent Arab population in the combined Jerusalem-Bethlehem entity.

The leaders of what became Israel indicated acceptance of the partition plan, but it was rejected by Arab leaders, who responded to Israel's declaration of independence the following year by going to war. The resulting conflict substantially redrew the map, as Israeli forces fought their way to Jerusalem and cleared much of the Palestinian population out of the coastal plain and the Gallilee. Whereas the original partition had allocated 55 percent of the territory to a Jewish state and 45 percent of it to a Palestinian Arab state, the war of 1948 put Israel in control of 78 percent of the territory. The remaining 22 percent, comprising Gaza and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem), was now controlled by Egypt and Jordan respectively.

Jerusalem remained a divided city, with the holy sites in the eastern part under Jordanian control. The international community continued to regard the city as having a distinct status.

The rough, hand-drawn lines on a map sketched by Israeli and Jordanian commanders in November of 1948, which later became the official 1949 Armistice Line, left parts of Jerusalem as a no-man's-land, outside either Israeli and Jordanian control. Special arrangements were made for Mount Scopus, which lay in the Jordanian controlled zone, but was home to an Israel hospital and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The 1949 Armistice Line, also known as the Green Line – or more colloquially as "the 1967 borders" – is often referred to in two-state negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians.

The war of June 1967, however, left Israel in control of the remaining 22 percent – the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Gaza. Israel then annexed East Jerusalem, redefining the municipal boundaries of the city to incorporate other West Bank towns and villages, making it the largest city in the country.

Despite the annexation, however, Palestinians in East Jerusalem were not granted citizenship of Israel in the way that those Palestinians who remained in the country after the 1948 war had been. Instead, East Jerusalem Palestinians were given “permanent resident” status, the same status as non-Jewish foreigners who moved to Israel, according to the Israeli human rights group B’tselem. East Jerusalem Palestinians live under constant fear of their Jerusalem identifications being revoked if they cannot prove their residency. B'tselem says 14,000 have suffered that fate since 1967.

Despite the international community – including Israel's staunchest ally, the U.S. – rejecting Israeli settlement in East Jerusalem, 12 Israeli settlement blocs housing more than 190,000 Jewish settlers have been built on occupied land in the city since 1967.

In 1980, Israeli Knesset passed the Jerusalem Law, which states that “Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel.” However, United Nations Security Council Resolution 478, adopted by 14 votes to none, with an abstention from the US, declared the law "null and void." No foreign country today has an embassy in Jerusalem.

Although Congress, in 1995, passed a law requiring that the U.S. Embassy be relocated from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, it allowed the executive branch the option of, every six months, signing a waiver on implementation that law. Since then, every U.S. president starting with Bill Clinton has, twice a year, waived implementation of that law.

The U.S. State Department’s continued recognition of Jerusalem as corpus serparatum has sparked a legal battle with the parents of 12-year-old Menachem Zivotofsky, a U.S. citizen born in Jerusalem whose birth certificate doesn't place the city in Israel. The U.S. Supreme Court is currently considering arguments about whether the State Department should be required to use "Jerusalem, Israel" on documents issued to U.S. citizens born there. Zivotofsky's birth certificate gives his birthplace simply as "Jerusalem."

The status of Jerusalem has proved to be a major stumbling block in efforts to forge a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Failure to reach agreement on the issue was a key reason for the failure of the 2000 U.S.-mediated Camp David negotiations between the Palestinian Liberation Organization and Israel mediated by the U.S.

The PLO demanded Palestinian sovereignty over Jerusalem east of the Green Line. Israel proposed giving the Palestinians custodianship over Muslim and Christian holy sites in East Jerusalem, but not sovereignty. The Israeli side also demanded that large settlement blocs in East Jerusalem would remain part of Israel.

Then opposition leader Ariel Sharon rejected even that offer by Israel's government, and took a large security contingent on a walking tour of the Temple Mount — also the precincts of the Islamic holy sites — triggering Palestinian protests that escalated into the Second Intifada...

The international community officially regards East Jerusalem as occupied territory. Additionally, no country in the world recognises any part of Jerusalem as Israel's capital, with the exception of Russia, which announced its recognition of West Jerusalem as the capital of Israel earlier this year.

As of now, all embassies are based in Tel Aviv.

Palestinians in Jerusalem

Despite Israel's de-facto annexation of East Jerusalem, Palestinians who live there were not granted Israeli citizenship.

Today, some 420,000 Palestinians in East Jerusalem have "permanent residency" ID cards. They also carry temporary Jordanian passports without a national identification number. This means that they are not full Jordanian citizens - they need a work permit to work in Jordan and do not have access to governmental services and benefits such as reduced education fees.

Palestinian Jerusalemites are essentially stateless, stuck in legal limbo - they are not citizens of Israel, nor are they citizens of Jordan or Palestine.

Israel treats Palestinians in East Jerusalem as foreign immigrants who live there as a favour granted to them by the state and not by right, despite having been born there. They are required to fulfil a certain set of requirements to maintain their residency status and live in constant fear of having their residency revoked.

Any Palestinian who has lived outside the boundaries of Jerusalem for a certain period of time, whether in a foreign country or even in the West Bank, is at risk of losing their right to live there.

Those who cannot prove that the "centre of their life" is in Jerusalem and that they have lived there continuously, lose their right to live in their city of birth. They must submit dozens of documents including title deeds, rent contracts and salary slips. Obtaining citizenship from another country also leads to the revocation of their status.

In the meantime, any Jew around the world enjoys the right to live in Israel and to obtain Israeli citizenship under Israel's Law of Return.

Since 1967, Israel has revoked the status of 14,000 Palestinians, according to Israeli rights group B’Tselem.

Settlements

Israel's settlemen projetc in East Jerusalem, which is aimed at the consolidation of Israel's control over the city, is also considered illegal Under international law.

The UN has affirmed in several resolutions that the settlement projetc is in direct contravention of the ourth Geneva Convention, which prohibits an occupying country from transferring its population into the areas it occupaies.

There are several reasons behind this: to ensure that the occupation is temporary and to prevent the occupying state from establishing a long-term presence through military rule; to protect the occupied civilians from the theft of resources; to prevent apartheid and changes in the demographic makeup of the territory.

Yet, since 1967, Israel has built more than a dozen housing complexes for Jewish Israelis, known as settlements, some in the midst of Palestinian neighbourhoods in East Jérusalem.

About 200,000 Israeli citizens live in East Jerusalem under army and police protection, with the largest single settlement complex housing 44,000 Israelis.

Such fortified settlements, often scattered between Palestinians' homes, infringe on the freedom of movement, privacy and security of Palestinians.

Though Israel claims Jerusalem as its undivided capital, the realities for those who live there cannot be more different.

While Palestinians live under apartheid-like conditions, Israelis enjoy a sense of normality, guaranteed for them by their state.

With the onset of the Oslo process, however, limited autonomy and self-rule was given to the Palestinians in the West Bank (though not in Gaza). The West Bank was divided into the following three administrative divisions, with civil administrative control of some areas transferred to the newly created Palestinian Authority (PA) while Israel maintained civil control over the majority of the territory. Under the terms of the Oslo process, full Palestinian governance was to have been achieved by 1999. But 15 years later, any Israeli transference of sovereignty remains elusive, especially with the presence in the West Bank of more than 300,000 Israeli settlers, more than twice the amount there during the signing of the Oslo Accords.

Area A

Comprising 18 percent of the West Bank, Area A is under PA civil control and security authority. Although it is comprised entirely of Palestinian cities – including Hebron, Nablus, Ramallah, Bethlehem and some towns and villages that do not border Israeli settlements – they are separated by areas controlled by Israel, including checkpoints, settlements and military outposts.

An exception is found in Hebron, the largest Palestinian city in the West Bank. While it lie in Area A, less than 1,000 Israeli settlers are living among hundreds of thousands of Palestinian residents, a state of affairs which prompted Israel to divide the city into two zones in the 1990s: H1, 80 percent of the entire city which is administered by the PA; and H2, 20 percent of the city which is controlled by Israel.

Palestinians from Area A cannot travel to other areas within the West Bank — even other parts of Area A — without crossing Israeli checkpoints. Despite Palestinian civil and security governance, Israel still maintains a de facto veto of final authority, sometimes raiding homes and businesses or detaining and arresting Palestinians.

Area B

Comprising about 22 percent of the West Bank, Area B is under Palestinian civil administration while Israel retains exclusive security control with limited cooperation from the Palestinian police. Area B includes more than 400 villages and farmland. Despite PA civil control, such areas are often threatened by the expansion of Israeli settlements into Palestinian land.

Area C

Under full Israeli civil administration and security control, Area C is the largest division in the West Bank, comprising 60 percent of the territory. The PA only has responsibility for providing education and medical services to the 150,000 Palestinians living there. With the exception of Hebron, all Israeli settlements are in Area C, where Israel has full authority over building permissions and zoning laws. Area C contains most of the West Bank's natural resources and open areas. More than 70 percent of the Palestinian villages in Area C are not connected to the water network while Israeli settlements are, according to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Israel's Civil Administration has planned for Palestinian development in less than 1 percent of Area C, and 99 percent of the area is off limits or heavily restricted for Palestinian construction.

Like the West Bank, East Jerusalem has been occupied by Israel since 1967 — which is illegal under international law.But Israel’s method of control over the territory differs. In 1980, Israel unilaterally declared Jerusalem a unified city, effectively consolidating power over Palestinian East Jerusalem, which would be the future capital of an independent Palestine as envisioned under the two-state Oslo process.

Unlike Palestinian residents of West Jerusalem and the rest of Israel, Palestinians living in East Jerusalem are given a unique identification card, which — unlike their Palestinian neighbors in the West Bank – allows them to travel throughout Israel and the West Bank. However, they are not granted an Israeli passport nor can they vote in Israeli élections.

Israel maintains full civil control in East Jerusalem, where they provide municipal services, health insurance and building permits to the Palestinian residents. Under its control over East Jerusalem, Israel has increased the presence of settlers around Palestinian towns and left other physical barriers separating those towns from the West Bank. According to the Israeli human rights organization B'Tselem, about 40 percent of the residents in annexed East Jerusalem are Jews living in settlements or previously-owned Palestinian homes.

Inside Story: Jerusalem, a momentous change, but at what cost?

PALESTINA

What it means to leave the Gaza Strip for the first time

Palestinian writer Mousa Tawfiq left Gaza via Israeli-controlled Erez checkpoint in September 2017, It was his first time seeing Palestine beyond the occupied Gaza Strip.

Political Tourism in Jerusalem

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário