Vladimir Putin wisely and honestly responds to questions about World War III, in 2018

What if Iran had its dissuasif nuclear weapon?

On January 3, US President Donald Trump announced triumphantly the killing of Iran's General Qassem Soleimani. Having assassinated the equivalent of a member of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, Trump claimed he did not want war. His words rang hollow in Tehran where this brazen attack was seen as an act of exactly that.

As many have noted so far, the assassination was carried out to help Trump's struggling re-election campaign. This strategy could have worked if Iran was a static player on the chessboard.

But it is not and depending on how it chooses to retaliate and the course of action it adopts vis-a-vis the US in the coming months and years, it could determine Trump's political fate. This episode along with other impulsive actions by the president will negatively affect the United States's regional position and its global role more broadly.

Only hours after the assassination, Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei stated that "a harsh revenge awaits the criminal killers". And after a meeting headed for the first time by him, Iran's supreme national security council issued a statement saying "the US regime will be responsible for all the consequences". If Trump expected Tehran to swallow the pain, he obviously miscalculated.

Soleimani was by far the most popular official figure in Iran; according to a 2019 poll, 82 percent of Iranians viewed him favourably. His assassination brought the nation together and made the need for revenge that more urgent. Beyond taking vengeance, a gradual shift in Iran's strategic conduct vis-a-vis the US and its client states in the region is expected - one that will be less tolerant of the US presence.

Soleimani rose to prominence from the lowest ranks in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in the 1980s and fought all of Iran's adversaries beginning with the Baathist Regime in the Iran-Iraq war all the way to ISIL (ISIS-Daesh).

He was the architect of Iran's "forward deterrence" in the region that rendered US anti-Iran efforts feckless and helped defeat ISIL. Soleimani's strategic vision was widely seen as essential to Iran's defence. Assassinating him, therefore, targeted first and foremost Iran's national security in the eyes of both Iranian officials and the Iranian public.

Hours after the assassination, Soleimani's deputy, Esmail Qaani, was appointed the new commander of the IRGC's Quds Force. The move was meant to refute speculations about a vacuum left behind by Soleimani but also to emphasise the continuation of Iran's regional strategy of "forward deterrence".

After the assassination, the Iranian leadership started debating when, where and how rather than whether or not to retaliate. Tehran is compelled to respond as its inaction would render its regional deterrence irrelevant, weaken "the axis of resistance" - the alliance of like-minded Middle Eastern states and political-military movements allied with Iran - and encourage the US's escalation.

Iran's geographic position, regional alliance and military capabilities, demonstrated recently in the downing of the sophisticated US spy drone in November and the targeting of ISIL positions in eastern Syria in 2016-17, gives it a wide range of options to respond.

The barrage of missiles which hit US bases in Iraq on January 8 was just the beginning - just a "slap" according to the Iranian Supreme Leader - and it seems to have been meant as a quick response to satisfy the public's cry for revenge. It fell short of being proportional to the assassination of Soleimani, which means one should expect more to come.

Iran is not likely to resort to rash action in the face of US escalation. It will most likely sleep on its options for quite some time before launching its response which will be marked by the traditional gradualism and steadiness of its regional conduct. Re-establishing deterrence on a new level would be the main objective of Iran's new course of action vis-a-vis the US escalation.

Though varied, Iran's options are all hard choices that can lead to further escalation. The US backing down after the January 8 missile attacks on its positions in Iraq decreased this possibility for now, but in the future, a tit-for-tat can easily spiral into a confrontation

Iran's main options include an increase in asymmetric warfare on an unprecedented scale to bleed the US in the region. Feeling attacked in Baghdad, the entire axis of resistance can be engaged in such a scenario.

Tehran might also resort to a devastating attack on one of the US's accomplice states such as Israel - as alluded to in the IRGC statement after the missile attacks in Iraq - that diminishes any sort of deterrence Washington thought the assassination could establish.

Other Iranian options include cyberattacks and indirect attacks on US assets and forces in the region.

Tehran knows that continuing domestic and international debates on Trump's foreign policy misconduct during this time can increase internal pressure on him, which it hopes to take advantage of.

It will try to show the American public, Trump's rivals within the US as well as its clients in the Middle East that the assassination will not in any way serve US interests or those of its allies. In doing so, Tehran will be pushing Trump into the hard place he tried to put Iran in: A retaliation would work against his campaign promise of pulling out of wars, while inaction would harm his reputation.

With Trump ordering the assassination as a way to show his decisiveness after being criticised for inaction against Iran's downing of the US spy drone, Iran's new course of action is likely to focus on hurting his reputation. Over the course of this year, this can affect his re-election campaign or taint his second term.

Soleimani's assassination also precluded any chance for a diplomatic win in the Middle East for the Trump administration.

In 2018, Trump killed the Iranian moderates' momentum by pulling out of the Iran nuclear deal and by reimposing sanctions. He has now killed the prospect for any future negotiations under his administration.

Iran has already shown signs it is willing to resurrect its nuclear programme. Declaring Iran's fifth step in reducing its Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action commitments, President Hassan Rouhani announced Tehran's move beyond many of its restrictions.

With public demand for revenge, Iranian missile attacks on US positions in Iraq and urgent geopolitical considerations Iran has to address, it is hard to imagine the re-start of negotiation with the US in the years to come.

What about American sanctions, will they be deterrent?

On the last day of 2019, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said that successive rounds of United States sanctions on Iran cost the country $100bn in oil revenue and another $100bn of investment money.

In a televised speech to the nation about what he called an "economic war", Rouhani blamed the dearth of vital foreign exchange currency on punitive US financial measures on Iran's oil and banking sectors.

That speech came just weeks after Rouhani proposed a "budget of resistance" to offset the "maximum pressure" campaign unleashed by Washington after Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the Iran nuclear deal with world powers in 2018.

"What should we do?" the Iranian president asked rhetorically. "When there is no food and water, you are still in danger no matter how strong you are."

Rouhani said Iran is paying a steep price for defying Trump's will - and that toll could worsen after Trump said during a news conference on Wednesday that the US "will immediately impose additional punishing economic sanctions" in response to Iranian missile attacks on US forces in Iraq.

The Trump administration says the goal of sanctions is to deprive Tehran of the capacity to fund "destabilising" activities and force its leaders back into nuclear discussions.

But the assassination of Quds Force CommanderQassem Soleimani and its aftermath raise important questions about whether sanctions have achieved those objectives - and whether the strategy is still viable.

There is no doubt that sanctions have been effective at pressuring Iran economically. Iran experienced the third-largest contraction of any national economy in the world during 2019, something very close to 10 percent. Iran has run deficits for years, but the government's fiscal gap widened exponentially as sanctions sent oïl sales plummeting 90 percent. The Iranian rial, which lost more than 60 percent of its value in 2018, has only partially recovered.

The Rouhani administration has tried to offset the ravages of sanctions by developing internal markets, cultivating new revenue streams and cutting subsidies - without fomenting a backlash from cash-strapped low- and middle-income people.

Such a dramatic transformation is tough for any country, let alone for one effectively isolated from the global economy and loath to reduce the costly enterprise of cultivating regional influence.

The scramble to refill rapidly depleting coffers has forced tough budget choices on Tehran. Over the summer, the government eliminated universal cash handouts to well-off households.

But the belt-tightening proved too much for ordinary Iranians in November, after a surprise government proposal to ration petrol and hike prices to fund cash benefits for the country's poorest citizens.

The proposal triggered nationwide protests. Blaming "thugs" linked to exiles and foreign adversaries, the government initiated an internet blackout and security crackdown that human rights group Amnesty International said in December resulted in at least 304 deaths. Iran categorically denied the findings.

But cost-cutting is just one of Iran's responses. Iran's strategy has evolved - from waiting out sanctions to compelling relief by upping the geopolitical ante for Washington and its allies. There was a series of regional attacks attributed to Iran, as well as Tehran's continued spending on military, security and intelligence, which Ibish says the government prioritises over "the wellbeing of the ordinary people". There is a very direct line of causality between the imposition of the sanctions and the situation in which Iran finds itself despite having tried to create a political and diplomatic crisis that would result in international intervention to force the US to ease the economic pressure.

I dont think that, at the moment, Tehran might be willing to renegotiate the terms of the nuclear deal with world powers, the limits of which it has now scrapped.

The political realities in Iran will not allow the Iranian government to negotiate directly. Mediation by third countries can help defuse the tensions, but if Trump was looking for a deal, he just ensured he won't be getting one. The maximum pressure campaign has succeeded in squeezing Iran's economy, but it has utterly failed in making Iran change its policies in the direction Washington wants.

Civilians have been most impacted by higher costs of living. The general tendency for sanctions is to make a population suffer. Something like using economic collective punishement. Just as Israel does to the Palestinians by daily terrorizing them and bombing Gaza once in a while.

Now let us go through how the assassination was carried and who unabled the crime.

Iranian General Qassem Soleimani arrived at the Damascus airport in a vehicle with dark-tinted glass. Four soldiers from Iran's Revolutionary Guards rode with him. They parked near a staircase leading to a Cham Wings Airbus A320, destined for Baghdad.

Neither Soleimani nor the soldiers were registered on the passenger manifesto, according to a Cham Wings airline employee who described the scene of their departure from the Syrian capital to Reuters.

Soleimani avoided using his private plane because of rising concerns about his own security, said an Iraqi security source with knowledge of Soleimani's security arrangements.

The passenger flight would be Soleimani's last. Rockets fired from a US drone killed him as he left the Baghdad airport in a convoy of two armoured vehicles.

Also killed was the man who met him at the airport: Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy head of Iraq's Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF), the Iraqi government's umbrella group for the country's militias.

The Iraqi investigation into the attack that killed the two men on January 3 started minutes after the US attack, two Iraqi security officials told Reuters. National Security agents sealed off the airport and prevented dozens of security staff from leaving, including police, passport officers and intelligence agents.

Investigators have focused on how suspected informants inside the Damascus and Baghdad airports collaborated with the US military to help track and pinpoint Soleimani's position, according to Reuters interviews with two security officials with direct knowledge of Iraq's investigation, two Baghdad airport employees, two police officials and two employees of Syria's Cham Wings Airlines, a private commercial airline which had its headquarters in Damascus.

The probe is being led by Falih al-Fayadh, who serves as Iraq's National Security Adviser and the head of the PMF, the body that coordinates with Iraq's mostly Shia militias, many of which are backed by Iran and had close ties to Soleimani.

The National Security agency's investigators have "strong indications that a network of spies inside Baghdad Airport were involved in leaking sensitive security details" on Soleimani's arrival to the United States, one of the Iraqi security officials told Reuters.

The suspects include two security staffers at the Baghdad airport and two Cham Wings employees - "a spy at the Damascus airport and another one working on board the airplane," the source said.

The National Security agency's investigators believe the four suspects, who have not been arrested, worked as part of a wider group of people feeding information to the US military, the official said.

The two employees of Cham Wings are under investigation by Syrian intelligence, the two Iraqi security officials said. The Syrian General Intelligence Directorate did not respond to a request for comment.

In Baghdad, National Security agents are investigating the two airport security workers, who are part of the nation's Facility Protection Service, one of the Iraqi security officials said. "Initial findings of the Baghdad investigation team suggest that the first tip on Soleimani came from Damascus airport," the official said. "The job of the Baghdad airport cell was to confirm the arrival of the target and details of his convoy."

The media office of Iraq's National Security agency did not respond to requests for comment, as did the Iraq mission to the United Nations in New York. The US Department of Defense declined to comment on whether informants in Iraq and Syria played a role in the attacks.

US officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, told Reuters the US had been closely tracking Soleimani's movements for days prior to the attack but declined to say how the military pinpointed his location the night of the attack.

A Cham Wings manager in Damascus said airline employees were prohibited from commenting on the attack or investigation. A spokesman for Iraq's Civil Aviation Authority, which operates the nation's airports, declined to comment on the investigation but called it routine after "such incidents which include high-profile officials.

Soleimani's plane landed at the Baghdad airport at about 12:30am on January 3, according to two airport officials, citing footage from its security cameras.

The general and his guards exited the plane on a staircase directly to the tarmac, bypassing customs.

Al-Muhandis met him outside the plane, and the two men stepped into a waiting armoured vehicle. The soldiers guarding the general piled into another armoured four-wheel drive, the airport officials said.

As airport security officers looked on, the two vehicles headed down the main road leading out of the airport, the officials said.

The first two US rockets struck the vehicle carrying Soleimani and al-Muhandis at 12:55am. The four-wheel drive carrying his security was hit seconds later.

As commander of the Revolutionary Guards' elite Quds Force, Soleimani ran clandestine operations in foreign countries and was a key figure in Iran's long-standing campaign to drive US forces out of Iraq.

What about Iraq in Trump's Was game?

The assassination o Qassem Soleiman and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, deputy head of Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the Iraqi government's umbrella group for the country's militias, has capsized Iraqi politics in the most dangerous of ways, making it possible that the country will be plunged once again into a state of permanent crisis and war from which it has escaped in the last two years.

Donald Trump is threatening sanctions against Iraq if it expels the 5,200 US military personnel in the country, while the Iraqi parliament has passed a non-binding resolution demanding the eviction of foreign troops after what it sees as a flagrant breach of Iraqi sovereignty.

The crisis over the presence of US troops on the ground in Iraq will get worse. The US troops returned to Iraq in 2014 to combat Isis after it captured Mosul and was advancing on Baghdad. The US forces were there "to provide logistics, intelligence and orchestrate US air support for Iraqi soldiers and paramilitaries fighting Isis". These anti-Isis forces consist of the Iraqi army and the Hashd al-Shaabi, or Popular Mobilisation Forces, the Shia paramilitary umbrella group, whose fighters are paid by the Iraqi government and headed by a senior Iraqi government official. Many of these paramilitary groups have Iranian links or are under Iranian control.

From the moment that a US drone killed General Soleimani and Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the leader of the powerful Kata’ib Hezbollah group, the priority for US troops in Iraq changed. It was no longer to pursue Isis and prevent its resurgence, but to defend its highly vulnerable bases from possible attack by Shia paramilitaries. This immediately relieved pressure on Isis which is trying to stage a comeback. The biggest cheer in Iraq after the US drone strike last Friday will have come from Isis commanders in their isolated bolt-holes in the desert and mountains of Iraq and Syria.

The US bases in Iraq are in fact more usually compounds within Iraqi military facilities. This means that from day one the US troops there are close to being hostages surrounded by potentially hostile Iraqis. Iraqi security units made no effort to protect the US embassy in the Green Zone in Baghdad last week. Even if the compounds are not directly assaulted or subjected to rocket fire self-protection, will be their priority.

Donald Trump, supported by his pals Jair Bozonaro, Boris Johnson and Binyamin Netanyahu, has justified the killing of Soleimani by pretending that his sole role in Iraq was to organise attacks on US and British forces. But the real history of the relations between the US and Iran since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990 has in fact been a strange mixture of rivalry and cooperation. This is not obvious because the cooperation was largely covert and the rivalry explicit. Iraqis, whose leaders balanced nervously between Washington and Tehran, used to say of them: “They wave their fist at each other over the table and shake hands under it.”

This contradictory approach stretches back 30 years: the US and Iran both vied to be the predominant foreign power in Iraq, but they also had dangerous enemies in common. The US had not finished off Saddam Hussein after his defeat in Kuwait in 1991, because they feared that his fall would open the door to Iranian influence. Washington changed its mind on this in due course and, by the end of the 1990s the CIA and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards both had bases in Salahudin in Iraqi Kurdistan that publicly ignored each other’s existence, but communicated privately through third parties.

Rivalry intensified after the US became the dominant power in Iraq after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. But in the long term both countries wanted a stable Shia government in power in Baghdad and realised that this could only happen if both the US and Iran agreed on Iraqi leaders acceptable to each other. Nouri al-Maliki was the choice of the US ambassador in Baghdad to be Iraqi prime minister in 2006 in the knowledge that Iran would approve – the British ambassador of the day objected and was shown the door.

This same system of joint decision-making at distance produced Maliki’s successor, Haider al-Abadi in 2014 and the current prime minister, Adel Abdul Mahdi, in 2018. The same convenient US-Iran arrangement decided the appointment of other senior officials, such as President Barham Salih, who was long close to the Americans, but was the surprising choice of Iran.

The common interest of these two outside powers was particularly close when Isis was at the peak of its strength between 2014 and 2017. The links were weakened by the election of Donald Trump as president in 2016, damaged further by his withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal in 2018, and finally destroyed by the assassination of General Soleimani.

A great danger in the present crisis is that Trump and his advisers know even less about Iraq than did George W Bush and Tony Blair in 2003. For instance, a problem about attacking the pro-Iranian Shia paramilitary groups is that they are part of the Iraqi state. The Iraqi interior minister always belongs to the Badr Organisation, a pro-Iranian grouping. The military muscle of the Iraqi security forces, which the US is in Iraq to support, comes in part from such groups with whom the US has just gone to war.

It is not a war that the US is likely to win, but it will inevitably reduce Iraq to chaos. Thanks to such confusion, with its enemies at each other’s throats, Isis may again take root and flourish. In the Islamic world, the killing of General Soleimani will be seen as not only anti-Iran, but anti-Shia. Everywhere conflicts are being stirred to life, of which Mr Trump knows nothing, but is about to find out.

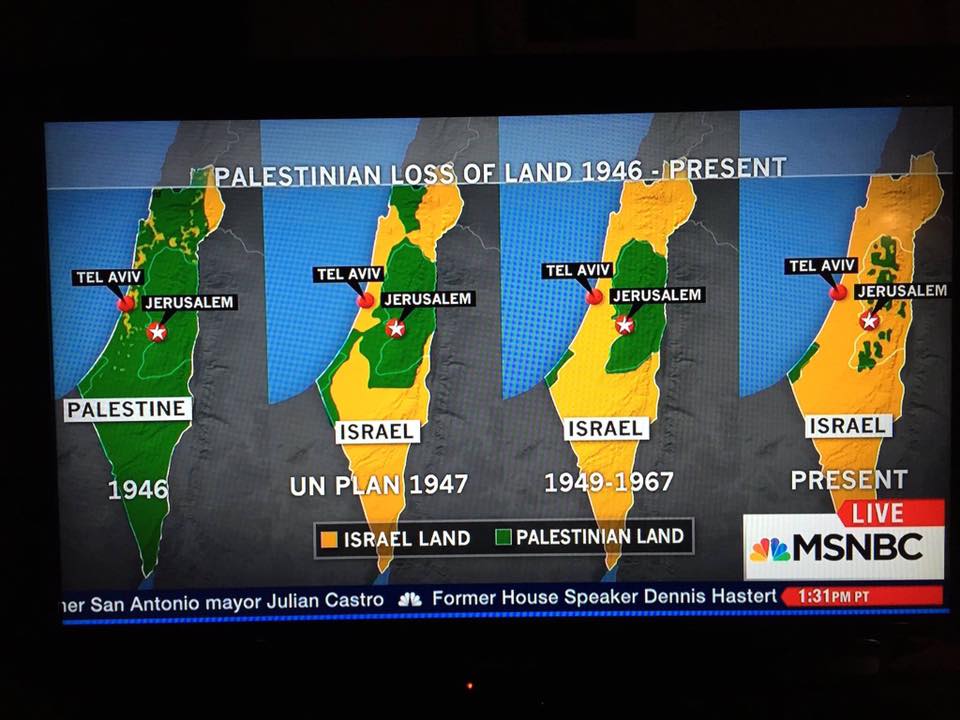

PALESTINA

Popular American game show Jeopardy has been plunged into controversy after a contestant was told she had the wrong answer after identifying Jesus's place of birth, the Church of Nativity in Bethlehem, as Palestine.

The incident took place in round one of the game broadcast on Friday, when Katie Needle was given the clue: "Built in the 300s A.D., the Church of the Nativity", under the category "Where's that Church?".

Needle, a retail supervisor, from Brooklyn, answered Palestine, but was told her answer was wrong.

One of the other two contestants, Jack McGuire, then buzzed in with the reply "Israel", which host Alex Trebek accepted as correct.

WRONG!

The Church of Nativity, declared a world heritage site, is located in Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank, which is internationally-recognised as part of Palestine.

Israel occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War of June 1967, in a move the international community has never recognised.

Christian pilgrims and tourists from across the globe visit Bethlehem throughout the year, specially on occasions like Christmas.

Jeopardy producers lwere not available for comment at the time of publication.

The episode was picked up by people on social media, with many criticising the show's producers and host and demanding that they apologise.

Omar Ghraieb, a Palestinian writer based in Gaza, said that "What happened is inexcusable. Jeopardy should apologise and give a clear explanation. This shouldn't just pass calmly and be forgotten."

Actually, this jeopardy incident just shows how normalised the occupation and cleansing of the Palestinian people from the historical record has become. The "incident" was an insult to history, to Christianity, to reality, and to the thousands of oppressed Palestinians of Bethlehem. Suffering under Israeli military occupation since 1967, Bethlehem has slowly been strangled. It has lost most of its land to settlement construction. It is hemmed in by a 30-foot-high concrete wall, stripped of its resources, and denied access to external markets.

The United Nations says Israeli settlements in Bethlehem and other parts of occupied West Bank are illegal, and has called them a "flagrant violation" of international law.

The Jeopardy incident contributes to the settler-colonial ideal of erasing Palestinians from their own cultural and religious sites - both in consciousness and in physical fact. While the audience is fed ahistorical propaganda, Israel often bars Palestinian Christians from Gaza from worshipping at Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity.

Christians in Gaza who plan to travel to the West Bank for Christmas or Easter have to apply for a temporary single-use permit to Israel from its Coordinator of the Government Activities in the Territories, which often arbitrarily denies many seeking the permit.

Jeoparday, the church of Nativity is in Bethlehem. Bethlehem is in Palestine. Jesus was born in Palestine. This is a fact. Not hasbara.

Needle, a retail supervisor, from Brooklyn, answered Palestine, but was told her answer was wrong.

One of the other two contestants, Jack McGuire, then buzzed in with the reply "Israel", which host Alex Trebek accepted as correct.

WRONG!

The Church of Nativity, declared a world heritage site, is located in Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank, which is internationally-recognised as part of Palestine.

Israel occupied the West Bank and East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War of June 1967, in a move the international community has never recognised.

Christian pilgrims and tourists from across the globe visit Bethlehem throughout the year, specially on occasions like Christmas.

Jeopardy producers lwere not available for comment at the time of publication.

The episode was picked up by people on social media, with many criticising the show's producers and host and demanding that they apologise.

Omar Ghraieb, a Palestinian writer based in Gaza, said that "What happened is inexcusable. Jeopardy should apologise and give a clear explanation. This shouldn't just pass calmly and be forgotten."

Actually, this jeopardy incident just shows how normalised the occupation and cleansing of the Palestinian people from the historical record has become. The "incident" was an insult to history, to Christianity, to reality, and to the thousands of oppressed Palestinians of Bethlehem. Suffering under Israeli military occupation since 1967, Bethlehem has slowly been strangled. It has lost most of its land to settlement construction. It is hemmed in by a 30-foot-high concrete wall, stripped of its resources, and denied access to external markets.

The United Nations says Israeli settlements in Bethlehem and other parts of occupied West Bank are illegal, and has called them a "flagrant violation" of international law.

The Jeopardy incident contributes to the settler-colonial ideal of erasing Palestinians from their own cultural and religious sites - both in consciousness and in physical fact. While the audience is fed ahistorical propaganda, Israel often bars Palestinian Christians from Gaza from worshipping at Bethlehem’s Church of the Nativity.

Christians in Gaza who plan to travel to the West Bank for Christmas or Easter have to apply for a temporary single-use permit to Israel from its Coordinator of the Government Activities in the Territories, which often arbitrarily denies many seeking the permit.

Jeoparday, the church of Nativity is in Bethlehem. Bethlehem is in Palestine. Jesus was born in Palestine. This is a fact. Not hasbara.

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário