It all began in 1905.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was led by a working class who, 12 years earlier had already tasted their own power and experienced bitter defeat.

The momentous year of 1917 was only eight days old when Russian activists took to the streets. On 9th January some 160,000 marched through St Petersburg in freezing temperatures, trailing past food queues and conscripts training for the front line. They marched to commemorate a massacre that had taken place 12 years earlier and was known as Bloody Sunday. The size of the commemoration was testimony both to the depth of the grievances of 1917 and to the continuing resonance of the events of 1905. When Russian workers created their revolution in 1917, they had already created a history of revolutionary struggle to guide them. The revolution of 1905 was the central component of that history.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 was led by a working class who, 12 years earlier had already tasted their own power and experienced bitter defeat.

The momentous year of 1917 was only eight days old when Russian activists took to the streets. On 9th January some 160,000 marched through St Petersburg in freezing temperatures, trailing past food queues and conscripts training for the front line. They marched to commemorate a massacre that had taken place 12 years earlier and was known as Bloody Sunday. The size of the commemoration was testimony both to the depth of the grievances of 1917 and to the continuing resonance of the events of 1905. When Russian workers created their revolution in 1917, they had already created a history of revolutionary struggle to guide them. The revolution of 1905 was the central component of that history.

The war-weary demonstrators of 1917 were remembering a time when anger generated by another military defeat animated protest movements. In 1905, it was Russian losses in a war with Japan which provoked dissatisfaction with the government and created conditions for a Liberal opposition movement to develop. This movement coalesced around demands for a legislative parliament. The Tsar’s response was couched in the paternalistic terms which legitimised his rule. Political reform, Tsar Nicholas explained, would be, ‘harmful to the people God has entrusted to me’.

However, amongst the people, there was a deep desire for change. On the 9th January 1905, a march of some 100,000 people tramped through the deep snow of St Petersburg’s streets. At the head of the march was a priest called Father Gapon. His congregation of impoverished city dwellers was mobilised by his belief that a benevolent Tsar would address their problems if only they could reach him. During the week leading up to the march, some 120000 workers went on strike in St Petersburg. Gapon, as head of the Russian Workers Assembly, seized the initiative and organised the demonstration to hand a petition to the Tsar. A few months later Gapon was exposed as a police spy and murdered by the comrades he betrayed.

However, amongst the people, there was a deep desire for change. On the 9th January 1905, a march of some 100,000 people tramped through the deep snow of St Petersburg’s streets. At the head of the march was a priest called Father Gapon. His congregation of impoverished city dwellers was mobilised by his belief that a benevolent Tsar would address their problems if only they could reach him. During the week leading up to the march, some 120000 workers went on strike in St Petersburg. Gapon, as head of the Russian Workers Assembly, seized the initiative and organised the demonstration to hand a petition to the Tsar. A few months later Gapon was exposed as a police spy and murdered by the comrades he betrayed.

The marchers carried religious icons and pictures of the Tsar but on their way to the Tsar’s Winter Palace they were confronted by a squadron of cavalry. Orlando Figes describes what happened next: ‘Some of the marchers scattered but others continued to advance towards the lines of infantry, whose rifles were pointed at them. Two warning salvoes were fired into the air, and then at close range, a third volley was aimed at the unarmed crowd. People screamed and fell to the ground. The soldiers, now panicking themselves, continued to fire steadily into the mass of people. Forty people were killed and hundreds wounded as they tried to flee. Gapon was knocked down in the rush. But he got up, stared in disbelief at the carnage around him, and was heard to say over and over again: ‘There is not God any long, there is no Tsar’.’

Other accounts put the number of deaths much higher, but what is beyond dispute is that the massacre marked a political shift the consciousness of many Russian workers. ‘In that one vital moment, the popular myth of a Good Tsar which had sustained the regime through the centuries was suddenly destroyed’, Figes writes. Alexandra Kollontai, who became a leading Bolshevik, was on the Bloody Sunday march. She described how the Tsar had unknowingly killed more than the people lying in the snow: He had also killed, ‘the workers’ faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new’.

A huge wave of strikes and protests erupted as news of the massacre spread across the Russian Empire. Students organised protests, while in the countryside peasants refused to pay their rent, seized land and burned down some 3,000 manor houses. The regime used the army to put down rural rebellions but by June the unrest had spread to the navy. There was a mutiny among sailors on the Battleship Potemkin, an event later made famous by film director Sergei Eisenstein. However, at the heart of the revolution were the waves of strikes which broke out repeatedly, dying down only to erupt again, with new demands and new displays of solidarity.

The revolution was at its strongest in countries which were part of the Russian Empire where resentment against Russian rule helped to fuel the protests. Around one-third of all the strikes that took place in the Russian Empire in 1905 took place in Poland. Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg smuggled herself into Warsaw to bear witness to events and to attempt to shape them. In February 1905 while the revolution was in full swing, Luxemburg described how she was witnessing the development of new, powerful social force.

Russia was a notoriously backward and undeveloped economy but in their rush to catch up with Britain, Germany and France the Russian ruling classes had succeeded in creating their own gravedigger. Luxemburg explained how Russian Tsarism had desperately attempted to transplant Western capitalism into Russia. ‘The bankrupt absolute regime, for fiscal and military purposes, needed railways and telegraphs, iron and coal machines, cotton and cloth. The absolute regime nurtured capitalism by the all the methods of pillaging the people and by the most ruthless policy of protective tariff – and thus unconsciously dug its own grave. It lovingly nursed the exploiting capitalist class – and thus produced a proletariat outraged at exploitation and suppression’. (Rosa Luxemburg, 1905).

The general strike was as geographically wide as it was socially deep. In Poland the ‘outraged proletariat’ was inspiring other sections of society: ‘The revolt of the industrial workers in late January and early February gave other independent social and political movements their cue.’ (Robert Blobaum, Rewolucia). Everywhere, striking workers were demonstrating their power and their capacity to lead others into struggle. The greatest revolutionaries were quick to grasp the significance of the workers’ action and eager to generalise their experience to other countries. Rosa Luxemburg wrote The Mass Strike in which she described how the revolutions of the past were characterised by street barricades and armed conflict with the state. In contrast, she wrote, in the revolutions of the future confrontation with the state would be only a moment in the process of proletarian struggle because workers would express their revolutionary energy through the mass strike movement. The interaction between economic and political demands meant that mass strikes could become the key method of generalising revolutionary struggle. The most precious aspect of the strikes was not the concessions that they won, but the ‘spiritual growth’, the political development of those participating in them.

The strike wave created the potential for workers to organise in new ways to meet the needs of the population. In St Petersburg, the home of some of the world’s biggest factories, this need was answered by the Council of Workers Deputies or Soviet. A young Jewish revolutionary known as Leon Trotsky was one of the elected leaders of the Soviet. He described its activities: ‘By pressure of strikes, the Soviet won the freedom of the press. It organised regular street patrols to ensure the safety of citizens. To a greater or lesser extent, it took the postal and telegraph services and the railways into its hands. It made an attempt to introduce the eight-hour day by direct revolutionary pressure. Paralysing the activities of the autocratic state by means of insurrectionary strike, it introduced its own free democratic order into the life of the labouring urban population.’ Some 50 other soviets were set up in other major cities to coordinate strikes and run key services under the control of the workers themselves. The workers demonstrated their ability not only to bring society to a standstill but also to organise it themselves in their own interests.

The strike wave created the potential for workers to organise in new ways to meet the needs of the population. In St Petersburg, the home of some of the world’s biggest factories, this need was answered by the Council of Workers Deputies or Soviet. A young Jewish revolutionary known as Leon Trotsky was one of the elected leaders of the Soviet. He described its activities: ‘By pressure of strikes, the Soviet won the freedom of the press. It organised regular street patrols to ensure the safety of citizens. To a greater or lesser extent, it took the postal and telegraph services and the railways into its hands. It made an attempt to introduce the eight-hour day by direct revolutionary pressure. Paralysing the activities of the autocratic state by means of insurrectionary strike, it introduced its own free democratic order into the life of the labouring urban population.’ Some 50 other soviets were set up in other major cities to coordinate strikes and run key services under the control of the workers themselves. The workers demonstrated their ability not only to bring society to a standstill but also to organise it themselves in their own interests.

The Tsar was forced to sign the October Manifesto which established a real parliament called the Duma. There was widespread jubilation across Russia. However, while the October Manifesto satisfied the middle classes and the Liberals, the workers and peasants had tasted their power and were demanding more fundamental change. Politics had moved to the streets and factories. Those who feared and detested the revolution began to organise. The Council of the United Nobility established the Black Hundreds which drew support from rich land owners, merchants, clergymen and policemen. They whipped up Monarchist fervour and unleashed anti-Semitic pogroms and violence against socialists and trade unionists. The Black Hundreds assisted the Tsarist regime in maintaining its rule. Their campaign of political terror gave Russians a glimpse of what regimes under pressure to change were capable of unleashing on their people and foreshadowed the fascist movements of the later 20th century.

The revolutionaries were also organising. In scenes that fore shadowed events of 1917, Lenin returned from exile in Geneva and immediately called for an armed uprising. He understood that the revolutionary forces were inexperienced, but he also understood that the process of revolution would transform the worker's movement. ‘To say that because we cannot win we should not stage an insurrection –that is simply the talk of cowards’, he declared. Trotsky argued that ‘retreat without battle may mean the party abandoning the masses under enemy fire’.

On 3rd December the leaders of the St Petersburg Soviet were arrested. In response the different factions of the socialist left, the Bolsheviks, the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries called a General Strike. The governor of Moscow tried to arrest the strike leaders and this provoked a city-wide uprising. Barricades were made of overturned trams and several districts were under rebel control for over a week. However, one railway station remained in the hands of the regime and this meant that troops could be to be brought in from St Petersburg. These regiments shelled the whole Presnia district, the heart of the uprising, and pulverised it into submission. General Min ordered a final assault, telling his troops, ‘Act without mercy. There will be no arrests’. The thousand rebels who were killed included 140 women and 80 children.

The experience of revolution in 1905 provided some indispensable lessons for the Russian Socialist Movement, in what workers’ power looked like and how to seize power. For Trotsky, the months between January and October 1905 revealed a vital truth about revolutionary movements in the 20th century. The Russian Revolution, ‘although directly concerned with bourgeois aims, could not stop short at those aims: the revolution could not solve its immediate, bourgeois tasks except by putting the proletariat into power. And the proletariat, once having power in its hands would not be able to remain confined within the bourgeois framework of the revolution.’ (Trotsky, 1905) To win, Trotsky argued, workers would have to confront not only ancient feudal structures but modern bourgeois relationships too. His theory of Permanent Revolution was developed out of the experience of 1905.

The revolutionary workers of 1905 had created a new form of organisation, the workers’ council or Soviet, which could direct and lead revolutionary struggle. In 1917, the Soviets would rise again to express the creative capacity of the working classes.

The marchers of 1917 commemorated those carried pictures of the Tsar as they were shot down on Bloody Sunday. They also commemorated those who just 10 months later were killed while fighting for a socialist society.

But the Socialists of 1917 were not content with remembering the past. They wanted to emulate the achievements of 1905 but with one crucial difference – this time they would win.

The revolutionary workers of 1905 had created a new form of organisation, the workers’ council or Soviet, which could direct and lead revolutionary struggle. In 1917, the Soviets would rise again to express the creative capacity of the working classes.

The marchers of 1917 commemorated those carried pictures of the Tsar as they were shot down on Bloody Sunday. They also commemorated those who just 10 months later were killed while fighting for a socialist society.

But the Socialists of 1917 were not content with remembering the past. They wanted to emulate the achievements of 1905 but with one crucial difference – this time they would win.

And they did.

And for seven decades they salvaged genuine reforms; particularly on the field of education and culture.

However, it came with a high price - freedom of speach and so many worthy lives.

Many questions remain, though.

Was Capitalism less lethal during the same period of time?

Is a democratic socialist society achievable?

Will one day men and women morally evolve to the point of becoming unselfish and just?

From where I stand, in terms of human evolution world wide, unfortunatelly, science and technology rapidly advance to make life easier and better (for some) but people are getting rather worse, actually.

This being said, I must add that I don't lose hope in individuals who want to do good and act on it against all odds.

Like Karl Marx, I am allowed to dream.

Like all human beings, hope is one of my leitmotifs.

And for seven decades they salvaged genuine reforms; particularly on the field of education and culture.

However, it came with a high price - freedom of speach and so many worthy lives.

Many questions remain, though.

Was Capitalism less lethal during the same period of time?

Is a democratic socialist society achievable?

Will one day men and women morally evolve to the point of becoming unselfish and just?

From where I stand, in terms of human evolution world wide, unfortunatelly, science and technology rapidly advance to make life easier and better (for some) but people are getting rather worse, actually.

This being said, I must add that I don't lose hope in individuals who want to do good and act on it against all odds.

Like Karl Marx, I am allowed to dream.

Like all human beings, hope is one of my leitmotifs.

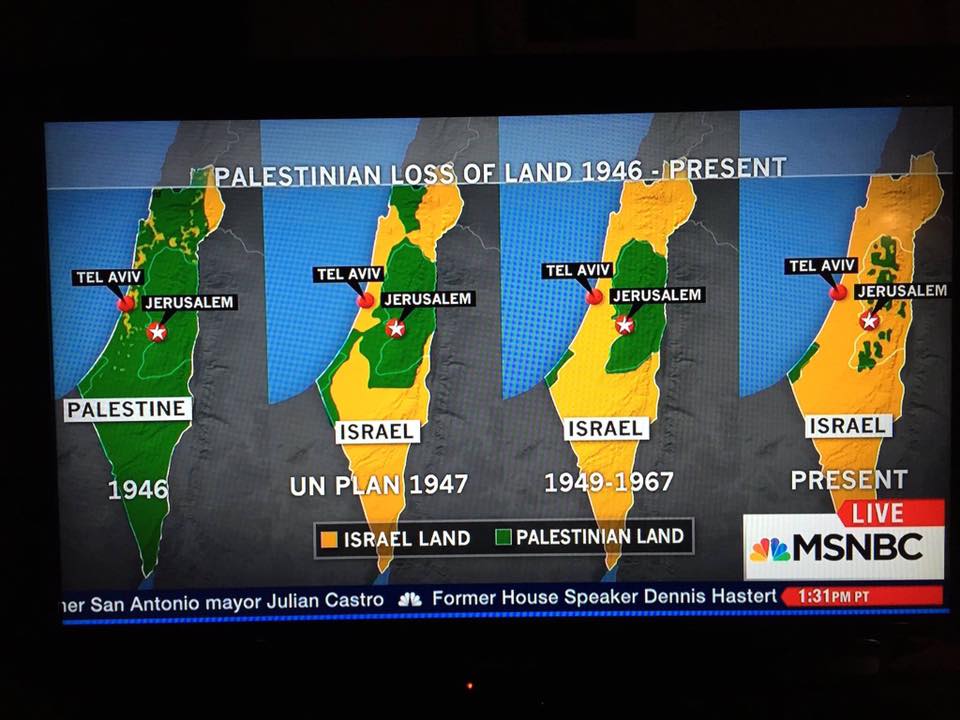

PALESTINA

DAILY LIFE UNDER OCCUPATION

Btselem.org/facing_expulsion_blog

Ben White: Don’t believe the hype about Israel’s Labour Party being prgressive …

UpFront: Can non violence end Israeli occupation?

BRASIL - DIRETAS, JÁ!

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário