Inside a Beirut bank, a security guard wearing a face shield slipped a wooden plank in between the handles of a heavy glass door as a swarm of customers waited outside. "Close the curtains," a teller ordered him from behind the counter. "We are closed!" It was barely noon. Two bank employees wearing masks handed out withdrawal forms and had them signed on car hoods. They were heckled by some in the crowd who shouted and shoved, elbowing each other to squeeze through the front doors.

This scene was mild compared to those that have unfolded in recent days and months: fistfights and jump kicks worthy of a WWE wrestling match. ATMs have been defaced and destroyed, and during the recent riots, some bank branches were attacked with firebombs, burned and gutted overnight.

It seems the coronavirus pandemic and social distancing have taken a backseat to the worst financial crisis Lebanon has ever seen, and this tiny Mediterranean country has seen many.

The street violence came as Lebanon's currency had been falling like a rock, losing value every day, experiencing an over 50 percent drop in its purchasing power against the US dollar since last October, when an uprising began, drawing hundreds of thousands into the streets.

The protesters called for the downfall of the government and an end to corruption and demanded living wages, better healthcare, electricity and other essential services they have been denied. Instead, they, and the rest of the population who did not protest, saw their salaries slashed, bank deposits evaporate and the price of basic foodstuffs double.

Almost half of Lebanon's citizens are projected to sink below the poverty level this year and the government estimates 75 percent of the population will require assistance. The Lebanese economy is now one of the weakest in the world, ranking only above Venezuela. All of this in a matter of months. How?

There always seems to be a simple answer, but it depends on who you ask.

Lebanon's new prime minister, Hassan Diab, who came to power amid the protests that brought down the previous government, has blamed his predecessors, especially the Central Bank Governor Riad Salameh, an incumbent of 26 years, for the crisis. Diab accuses Salameh of pursuing unsound and untransparent fiscal policies.

The currency devaluation can be partly blamed on the country's plummeting credit scores, which have been downgraded repeatedly in recent months, due to political turmoil and fears over the government's ability to repay its mounting public debt, one of the highest in the world.

Diab also claimed that some $5.7bn was taken out of Lebanese banks in January and February of this year, despite capital controls, encouraging a widespread suspicion of foul play and preferential treatment for big investors.

But Governor Salameh rejected the claim, saying that $3.7bn was used for loan payments and $2.2bn was withdrawn mostly in local currency, so it could not have left the country.

He claimed that the banks should be credited, not faulted for bailing out the state repeatedly over the last three decades and that the government has only itself to blame for its overspending and bankruptcy. This was compounded, he added, by Diab's decision to default on a debt payment for the first time in March, which only sent more jitters into the market.

Indeed, it is difficult to imagine any financial system that could withstand such pressures: nearly every customer clamouring to liquidate their accounts as fast as possible. On the other hand, bank profits have soared on Salame's watch, amounting to some $22bn since 1993, while wages and public services have stagnated or gone down.

The protesters, fed up with inequality and worsening living conditions, have blamed both Salameh and Diab and the entire political system of Lebanon, including nearly every politician and political party the country has ever known. That is quite a wide net in a political landscape that ranges from the far right to far left, pro-American to pro-Iranian: capitalists, communists, leftists, Islamists, fascists, neoliberals, post-colonial feudalists, militiamen, billionaires and bankers.

What all these actors have in common according to those in the streets is one simple word: corruption. It is a powerful, although intangible term. Its mere utterance evokes a certain catharsis with little need to elaborate. "Kelun Yani Kelun! [All means all!]" is the main protest slogan shouted at rallies and marches for more than six months now. Everyone must go. "A pack of thieves!" is the constant refrain.

This sentiment is echoed, albeit in more polite tones, in the dozens of articles and reports about Lebanon's malaise published over recent months by Western media outlets and think-tanks. The culprit behind "endemic corruption", they often report, is similarly singular and simplistic: the political class, the ruling elite or some variation thereof.

These terms are used so routinely and interchangeably, the paragraphs almost write themselves. They become bland and repetitive like any vague, overarching claim. Yet they also voice an inherently moralistic position.

The solution, analysts claim, is straightforward: admit wrong and "reform" the bad ways of the past, end the corruption, establish credibility, embrace transparency, accountability, the rule of law. Repent for your sins.

The consequences of inaction are similarly biblical: a perfect storm of wrath and rage, implosion, free fall, a big mess "teetering on the brink of economic ruin and political chaos" as the Washington Post recently put it.

But one thing these diagnoses tend to miss is detail: figures, names, a smoking gun to close the case on this alleged cesspool of depravity.

The evidence presented against "the corrupt class" even in the "most reputable" Western news agencies and newspapers is largely circumstantial: decrepit public services operating at a significant loss, an uncontrolled currency crisis, a lack of social welfare programmes, the high cost of living, unemployment, negative GDP growth. Are these really symptoms of bad moral behaviour from a handful of really bad men?

If corruption - or "thievery" as protesters call it - could cause this much damage, then why hasn't it paralysed wealthier countries? In the United States, for example, it is not billions but trillions of dollars that are wasted every year, on inflated military and infrastructure contracts, corporate bailouts, failed projects and programmes, tax evasion and avoidance.

There has been much criticism of Lebanon's old patronage networks that keep power concentrated in the hands of the few. But how different are they to the unnecessary and politicised allocations of taxpayer funds by members of the US Congress to bring jobs and contracts to their local districts known as "pork barrel spending"?

Similarly, many have faulted Lebanon's banking system as an elaborate Ponzi or pyramid scheme, in line with the stereotype of the unscrupulous Lebanese businessman. But how unique is debt risk and reshuffling in the world of business and finance?

Some Wall Street insiders have likened much of what goes in the stock market, the US Social Security Fund and even the Federal Reserve to a Ponzi scheme of sorts. Trillions of dollars evaporated from accounts during the subprime real estate crisis. Yet there was no currency collapse, no electricity shortages, no run on the banks in the US. And in terms of the much-vaunted accountability Lebanese officials are expected to face in order to save the country, rarely has a major Wall Street broker or banker ever been sent to prison.

Those now waving their fingers at Lebanon over its financial misconduct should be reminded that the architects of the country's postwar economy came largely from prominent US financial institutions.

The late billionaire Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, who engineered massive reconstruction spending that racked up the national debt, surrounded himself with veterans of global financial institutions who spearheaded a "liberal" investment strategy to draw in foreign capital, marked by low taxes and little regulation.

Among the members of this dream team were former Finance and Prime Minister Foaud Sinora, who worked at Citibank, as well as Salameh, the Central Bank governor, who served as vice president of Merrill Lynch in Paris.

For decades, Hariri and his entourage and their policies were welcomed and praised in Western capitals. Salameh was even voted Central Bank governor of the year in 2009 by the Banker magazine, a subsidiary of the Financial Times, best central banker in the world by Euromoney in 2006, an award of honour from the French president, among other accolades. As recently as last year, he was given an "A" rating by Global Finance, outperforming his counterparts in several European countries including Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Looking back, there is much criticism of these neoliberal policies evangelised by the global financial industry, and for good reason. They are top-down, market-driven equations that prioritise investors over workers, profits over social welfare programmes and the environment. But how can these policies explain Lebanon's unique "mess" if supply-side or "trickle-down" economics have been implemented all over the world?

Could it be that neoliberal policies are far more damaging for small, war-torn countries that lack strong institutions, political stability, natural resources or major manufacturing industries? Such countries are already considered high risk, lack investor confidence and thus pay a high cost for borrowing.

Consider this on the individual level: how hard is it for someone to climb out of bad credit? It is easy to blame their poor decisions and upbringing. It is more difficult to examine the circumstances that led to their misfortune because this necessitates putting one's own privileges under a microscope.

Like neoliberalism, corruption and cronyism are also not absent from most political and financial systems. But they too have a far greater impact when there is not enough money in the economy to keep people quiet.

Even if we were to dismiss all of the above, this still leaves the favourite scapegoat for Lebanon's woes: sectarianism.

It is loathed particularly by younger generations, who grew up after the war and are rightly puzzled by its relevance and ability to empower a handful of parties to wield so much control over the state. But here too there are parallels to partisanship, an inescapable reality even in the most successful countries.

After all, it is not really sects or political parties that take decisions at the end of the day, but groups of influential persons at their helm, largely wealthy, largely male, those who sign the big contracts and help write the legislation that guarantees them. In developing countries, it is called clientelism, whereas, in more developed nations, it is known as lobbying, political action committees and excellent legal teams.

This may explain part of the reason why rich countries rank so low on corruption indexes: the language is different.

None of this is to say bad governance and stark wealth disparities should be ignored. But some perspective could help the ways we demand and fight for better systems.

Having spent several years investigating many Lebanese government problems - wasteful public works projects, overpriced telecommunications, unreliable electricity, destructive land use and pollution - I, like many of my colleagues, struggle to identify clear-cut, prosecutable charges of corruption and culprits, ie bad guys and bogeymen.

When we dive into the abyss of public sector failures, what we usually find instead are labyrinths and layers of structural problems that have been mounting for decades. These include outdated, malfunctioning infrastructure, understaffed and underfunded facilities, a lack of maintenance and monitoring.

These problems are further compounded by defunct or non-existent oversight bodies to act as a watchdog on industry and contracts, unclear jurisdiction and conflicting views from different government agencies over who is responsible, slow, ineffective and inaccessible courts.

Of course, this convoluted environment provides many opportunities for exploitation, but more often, this is done through legal loopholes and not the glaring robberies our imaginations can conjure.

Contrary to popular opinion, these are not necessarily problems wedded to personalities that are currently in power. It is not only their annoying mannerisms and snarky smiles that should draw our attention and ire, but hundreds of local and national elected officials and bureaucrats making thousands of decisions on a daily basis, voted in by millions of citizens, many enjoying some benefit from the "ruling class" and its patronage economies.

This discussion of power relations brings us to the final and perhaps most popular argument to explain Lebanon's financial problems: warlords. Here is another visceral term, like corruption, in which we have become accustomed to depositing our well-justified anger and angst.

But once again, we must ask ourselves how we imagine political structures around the world were established, particularly those most economically powerful and admired today. Is a state not formed through war? By tribes and clans and militias and bloody battles between them?

One difference with Lebanon is that no victor prevailed, the warlords or "the founders" have not given up, the other side has not been conquered to make way for an "indivisible" nation built on the bones of its detractors.

In many ways, Lebanon is unfinished business. It is frozen in the embryonic stage of nation-building, the militias have evolved into parties, but only in name. No system keeps them in check, there is no higher power to adjudicate conflicts and settle jurisdictions, no agreed-upon law enforcement to have a rule of law. Each side can justify its transgressions as part of the ongoing battle.

Cynics will say this void is Lebanon's fate, destined to be a wasteland, a chessboard where major powers can manoeuvre and manipulate to settle scores without getting their hands (or countries) dirty. The decades of nearly uninterrupted war, from its founding during World War II to the itinerant street battles, air strikes and assassinations of recent years testify to that. No side could have kept up the fight without external support.

Curiously, this militarism from foreign states is rarely included in analyses of corruption in Lebanon. In particular, the billions of dollars in destroyed infrastructure, inflicted upon roads, bridges and power stations over decades of Israeli air strikes with the support of American-made bombs and political power, the untold losses to tourism, shipping and other industries are almost never included in tallies of corruption and economic losses. Lebanon also pays the cost of foreign-funded wars in neighbouring countries, accepting more refugees per capita than any other country in the world, putting an undeniable added strain on already-collapsing employment, services infrastructure.

All of these factors will continue to complicate Lebanon's options going forward. The new government, consisting largely of unknown individuals and college professors, some of them advisors to political parties, have made some ambitious proposals. On the surface, their tone is more serious than their predecessors' and they have been more responsive to public demands, arresting business owners accused of price gouging, and demanding a full audit of the central bank's activities.

But they are being sharply criticised, particularly their bid to ask for billions of dollars in assistance from the IMF and their failure to call for immediate elections and rid the country of corruption more rapidly.

Indeed, the government's every action should be scrutinised. Renewed demand for accountability and investigations is one positive aspect of the uprising culture the protests have helped inspire.

But analyses that fail to contextualise the daunting, historical, structural and geopolitical challenges even the best possible Lebanese government would face, are telling only part of the story.

Fear, like corruption, stability and creditworthiness are intangible indicators often assessed and determined by those in far more privileged and powerful positions than any politician or bureaucrat in Lebanon. Global institutions help determine the country's fate but do not share its national interests.

As always, Lebanon will continue to face an uphill battle in attracting foreign capital, perhaps now greater than ever before. Not only are there the concerns about security - a stigma stretching back over 40 years - but also about the solvency of the country's financial system, which has never faced a challenge of this magnitude even during the height of civil war shelling.

How realistic is it to expect Lebanon to build a competitive industry from an already weakened position with no natural resources, strong central government or significant technical know-how to call upon?

Aside from a few light industries, such as food, jewellery and paper, Lebanon simply does not make much, nor does it have the basic infrastructure to do so in major quantities. Tapping into the country's abundance of nature and historic sites is also beset again by "confidence" concerns, travel warnings from the world's most powerful nations and deep-set negative perceptions that have kept wondrous ancient and natural sites largely empty. US sanctions, and a ban on direct flights since the civil war, have not helped either.

There is some hope that potential oil production and renewed interest in cannabis growing (long banned under US pressure) could come to the rescue. Neither is anywhere near certain as the fact that new loans will bring renewed borrowing costs, new political strings attached with increasingly difficult and potentially dangerous conditions to meet.

All of these future developments and financial transactions should be followed closely. But in doing so, we should resist the lure of reductive conclusions to create neat paragraphs and easily digestible analyses and tired moralistic stereotypes that appeal to international audiences and publishers. Pointing the finger at localised bad behaviour avoids a more serious conversation about the injustices of global finance.

There are no easy answers to explain the story of Lebanon - it is essentially the story of a country under constant military attack of Israel and economical threat from the USA; and also the story of many countries and peoples and circumstances that reflect our interconnected political and economic realities, shared vulnerabilities and darkest fears. Be wary of fairy tale narratives about villains and heroes and missed opportunities for happy endings.

PALESTINA

5.000 Palestinian political prisoners, including children, women, elderly and sick detainees, are, at this right moment, besieged by two virus: COVID19 & Israel occupation

On May 15, thousands of Palestinians in Occupied Palestine and throughout the ‘shatat’, or diaspora, participated in the commemoration of Nakba Day, the one event that unites all Palestinians, regardless of their political differences or backgrounds.

For years, social media has added a whole new stratum to this process of commemoration. #Nakba72, along with #NakbaDay and #Nakba, have all trended on Twitter for days. Facebook was inundated with countless stories, videos, images, and statements, written by Palestinians, or in global support of the Palestinian people.

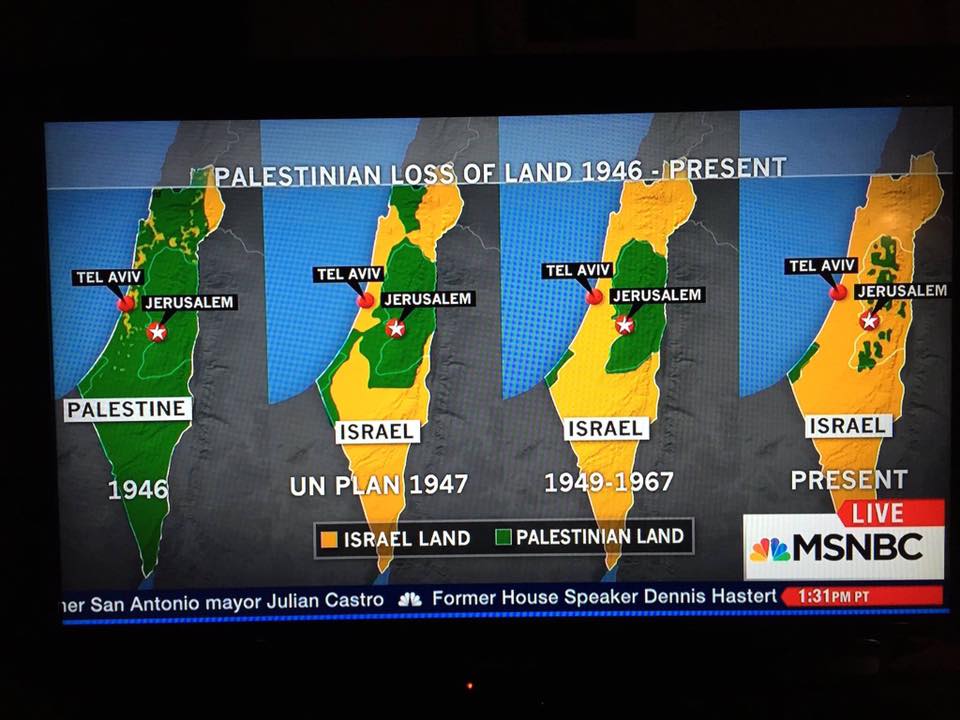

The dominant Nakba narrative remains – 72 years following the destruction of historic Palestine at the hands of Zionist militias – an opportunity to reassert the centrality of the Right of Return for Palestinian refugees. Over 750,000 Palestinians were ethnically cleansed from their homes in Palestine in 1947-48. The surviving refugees and their descendants are now estimated at over five million.

As thousands of Palestinians rallied on the streets and as the Nakba hashtag was generating massive interest on social media, US Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, paid an eight-hour visit to Israel to discuss the seemingly imminent Israeli government annexation, or theft, of nearly 30% of the occupied Palestinian West Bank.

“The Israeli government will decide on the matter, on exactly when and how to do it,” Pompeo said in an interview with Israeli radio, Kan Bet, the Jerusalem Post reported.

Clearly, the Israeli government of Binyamin Netanyahu has American blessing to further its colonization of occupied Palestine, to entrench its existing Apartheid regime, and to act as if the Palestinians simply do not exist.

The Nakba commemoration and Pompeo’s visit to Israel are a stark representation of Palestine’s political reality today.

Considering the massive US political sway, why do Palestinians then insist on making demands which, according to the pervading realpolitik of the so-called Palestinian-Israeli conflict, seem unattainable?

Since the start of the peace process in Oslo in the early 1990s, the Palestinian leadership has engaged with Israel and its western benefactors in a useless political exercise that has, ultimately, worsened an already terrible situation. After over 25 years of haggling over bits and pieces of what remained of historic Palestine, Israel and the US are now plotting the endgame, while demonizing the very Palestinian leaders that participated in their joint and futile political charade.

Strangely, the rise and demise of the so-called ‘peace process’ did not seem to affect the collective narrative of the Palestinian people, who still see the Nakba, not the Israeli occupation of 1967, and certainly not the Oslo accords, as the core point in their struggle against Israeli colonialism.

This is because the collective Palestinian memory remains completely independent from Oslo and its many misgivings. For Palestinians, memory is an active process. It is not a docile, passive mechanism of grief and self-pity that can easily be manipulated, but a generator of new meanings.

In their seminal book “Nakba: Palestine, 1948, and the Claims of Memory”, Ahmad Sa’di and Lila Abu-Lughod wrote that “Palestinian memory is, at its heart, political.”

This means that the powerful and emotive commemoration of the 72nd anniversary of the Nakba is essentially a collective political act, and, even if partly unconscious, a people’s retort and rejection of Donald Trump’s ‘Deal of the Century’, of Pompeo’s politicking, and of Netanyahu’s annexation drive.

Despite the numerous unilateral measures taken by Israel to determine the fate of the Palestinian people, the blind and unconditional US support of Israel, and the unmitigated failure of the Palestinian Authority to mount any meaningful resistance, Palestinians continue to remember their history and understand their reality based on their own priorities.

For many years, Palestinians have been accused of being unrealistic, of “never missing an opportunity to miss an opportunity,” and even of extremism, for simply insisting on their historical rights in Palestine, as enshrined in international law.

These critical voices are either supporters of Israel, or simply unable to understand how Palestinian memory factors in shaping the politics of ordinary people, independent of the quisling Palestinian leadership or the seemingly impossible-to-overturn status quo. True, both trajectories, that of the stifling political reality and people’s priorities seem to be in constant divergence, with little or no overlapping.

However, a closer look is revealing: the more belligerent Israel becomes, the more stubbornly Palestinians hold on to their past. There is a reason for this.

Occupied, oppressed and refugee camps-confined Palestinians have little control over many of the realities that directly impact their lives. There is little that a refugee from Gaza can do to dissuade Pompeo from assigning the West Bank to Israel, or a Palestinian refugee from Ein El-Helweh in Lebanon to compel the international community to enforce the long-delayed Right of Return.

But there is a single element that Palestinians, regardless of where they are, can indeed control: their collective memory, which remains the main motivator of their legendary steadfastness.

Hannah Arendt wrote in 1951 that totalitarianism is a system that, among other things, forbids grief and remembrance, in an attempt to sever the individual’s or group’s relation to the continuous past. The same definition Apply for the Zin onist project against which this great philosopher stood in her days. For decades, Israel has done just that, in a desperate attempt to stifle the memory of the Palestinians, so that they are only left with a single option, the self-defeating peace process.

In March 2011, the Israeli parliament introduced the ‘Nakba Law’, which authorized the Israeli Finance Ministry to carry out financial measures against any institution that commemorates Nakba Day.

Israel is afraid of Palestinian memory, since it is the only facet of its war against the Palestinian people that it cannot fully control; the more Israel labors to erase the collective memory of the Palestinian people, the more Palestinians hold tighter to the keys of their homes and to the title deed of their land back in their lost homeland.

There can never be a just peace in Palestine until the priorities of the Palestinian people – their memories, and their aspirations – become the foundation of any political process between the Jewish immigrants and the indigenous people, that is, between Israelis and the Palestinians. Everything that operates outside this paradigm is null and void, for it will never herald peace or instill true justice. This is why Palestinians remember; for, over the years, their memory has proven to be their greatest weapon.

"I'm Under lockdown, but not because of coronavirus"

"In the last few months, due to the coronavirus pandemic, millions of people around the world experienced for the first time the difficulties and frustrations of living under state-imposed rules and regulations that restrict their freedom of movement.

For me, however, the lockdown was nothing new. I am used to living under shifting sets of rules which define where I can go and what I can do. Why? Because I am a Palestinian living under Israeli occupation.

I grew up in the occupied West Bank, so checkpoints and curfews have always been a part of my daily life. Last year, Israel made my prison even smaller by barring me from leaving the West Bank for any reason.

The Israeli authorities refused to give any justification for the ban beyond "security reasons", and denied that the move has anything to do with my job as Amnesty International's Israel/Palestine Campaigner.

I learned about the ban in the worst possible way, when I was denied a permit to accompany my mother to her chemotherapy appointments in occupied East Jerusalem last September. While I was frantically reapplying for permits, my mother was getting sicker. I was only a 15-minute drive away from the hospital, but my desperation to be with my mother was no match for Israel's rigid enforcement of the permit system. My mother passed away on Christmas Eve before I could ever see her again.

The "security reasons" which caused me so much heartbreak have not been revealed to me to this day. All I know is that I am under a full travel ban, which means I cannot travel outside the West Bank, even to my office, which is in East Jerusalem. The COVID-19 lockdown, which has been in place since March 22, therefore, is nothing but another bar on the cage I have long been living in.

I will never get back that precious opportunity to be with my mother in her last days, but I can do right by her by challenging this injustice. On March 25, 2020, Amnesty International submitted a petition to the Jerusalem District Court seeking to have my travel ban lifted, and a hearing will take place on May 31. It will be held in my absence, of course - and since I am not allowed to know the details of the allegations against me, my lawyer and I cannot meaningfully challenge them.

Still, in the past, travel bans against Palestinians have crumbled under legal scrutiny. Between 2015 and 2019, Israeli rights organisation HaMoked filed 797 travel ban appeals, and succeeded in getting 65 percent of these lifted. Looking at this outcome, it is reasonable to assume that most of these bans were completely unjustified in the first place.

Israel has a track record of using arbitrary travel bans against human rights defenders, including Omar Barghouti, a cofounder of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) movement, and Shawan Jabarin, director of Palestinian rights organisation al-Haq. In Shawan Jabarin's case, as in mine, no justification was given beyond "security concerns".

What does that mean? If I am such a grave security risk you would expect the Israeli authorities to have questions for me. But I have never been questioned about any security issues, not even at a border crossing, just turned away. I have never been given the chance to challenge the decision or defend myself. How is this fair?

Two million Palestinians living in the Gaza Strip have been under a brutal military blockade for more than 12 years, making it the biggest open-air prison in the world. We, in the West Bank, cannot travel internationally through Israel's seaports or the Ben Gurion International Airport - our only option is to travel into Jordan using the Allenby/King Hussein border crossing. Many people do not realise that they are banned from travelling until they arrive at the crossing. Last October, for example, I wanted to attend my aunt's funeral in Jordan; when I arrived at the crossing with my father and my suitcase, I was denied entry.

There are so many stories like this. The COVID-19 lockdown has given people the world over a glimpse into the Palestinian experience - the sadness of being separated from loved ones, the boredom of confinement, the fear and the sense of isolation. While coronavirus lockdowns were enacted to protect populations from a deadly virus, Israel's lockdown deprives Palestinians of freedom of movement as a form of collective punishment.

Like so many people around the world, I hope that I will soon be able to return to my office, see my friends and family in other cities, and experience the excitement of travelling somewhere new. After 72 years of displacement and injustice, Palestinians want and deserve the same rights and freedoms as everybody else." Laith Abu Zeyad

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário