While

countries around the world have been rolling out emergency measures to respond

to COVID-19, and with millions of people contaminated and hundreds of thousands

deaths, few are actually prepared for what a post-pandemic world will look like

- the demands it will make of the societies left to populate it, and the extent

to which it will blunt the confidence and hyper-individualism that has

characterised the 21st century thus far.

At

the end of World War II, the need for a global framework based on shared values

and interdependence rallied political and policy elites to the cause of a

liberal international order. In the 70-odd years that followed, that framework

was gradually eroded by the combined forces of globalisation, poverty and the

unresponsiveness of mainstream political parties to local discontent.

Until

a few months ago, it seemed almost certain that the resurgence of the political

right from Brasil to Hungary, and India to the United States would

unambiguously come to define the remainder of the 21st century.

Autocracies would consolidate. Exclusion and xenophobia would dominate election

promises; and events such as the European migrant crisis would further the

logic for nativism and tougher rules on immigration and protectionism.

But

will the pandemic, the deadliest since the Spanish influenza, change all that?

Or will the neo-authoritarian character of the last two decades, culminating

dramatically in Britain's exit from the EU, be immune to the indiscriminate,

deadly spread of COVID-19, and the consequences of its universal reach?

While

even the liberal global north takes drastic steps to isolate, quarantine and

restrict the movement of citizens, in the long-term, the pandemic will likely

demonstrate that a world without safety nets, cooperation and deep cross-border

engagement is no longer tenable. Leaders and electorates will have to answer

tough questions about why they were caught unprepared, and the sustainability

of a planet dictated by climate deniers and political chauvinists whose ascent

to power has been enabled by a tradition of misrepresentation, manipulation,

and misinformation.

As

a result of COVID-19, governments not just in Europe, but from America to Asia,

have been forced overnight into solidarity and cooperation: coordinating

international travel rules, sharing information about public health management

strategies, fact-checking domestic news, and exchanging scientific expertise.

Like the Marshall Plan that rebuilt Western Europe, governments will soon need

to cooperate over fiscal stimulus and trade. That will be a big task for an

international system that, under the U.S.A.’s "go-it-alone" unipolar

shadow, has been largely inward-looking, driven by a lack of disruptive

innovation, and eschewed any real alignment of national plans or priorities.

Amid

a scalding oil-price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia, oil producers are now

being forced to discuss how best to stabilise the price of the commodity

against a backdrop of the pandemic.

American

legislators have called on the US to revisit its "maximum pressure

policy" of sanctions on Iran that have hit the country's ability to import

medical supplies. Tehran, for the first time in six decades, has approached the

IMF to help it fight the coronavirus outbreak. In the Far East, members of

Japan's ruling Liberal Democratic Party have voted to donate their monthly

salaries to help arch-nemesis China fight the outbreak. In response,

Chinese social media quickly filled with gratitude for Japanese well wishes.

As

the pandemic peaks, populists,in power, just like what happened to rump, will

inevitably face a credibility crisis. Many, such as Donald Trump in the United

States, Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil and Narendra Modi in India, were sufficiently

adept at dealing with emergencies geared at otherising a convenient enemy,

immigrants in the case of the former, Muslims in the case of the latter. But in

the pandemic, there is no visible, ethnically identifiable "other" to

strong-arm. Populists will face criticism for their inability to effectively

respond and contain the spread of the disease. It is for this reason, perhaps,

that Indian Prime Minister Modi hurriedly turned to technology by holding a

videoconference between heads of South Asian Association for Regional

Cooperation (SAARC) member states this week. But the fact remains that India

under Modi's authoritarian spell spent the last five years working against

regional integration, instead ratcheting up neighbourhood tensions, including a

lockdown and Internet shutdown for eight million people in the disputed

territory of Kashmir.

Finally,

in China, where the outbreak began, and where the rules against social media

bloggers and activists are strict, even the Communist Party has been forced to

realise the costs of restricting the flow of information in tackling the

outbreak, and the countervailing power of social media and the digital public

sphere in daily governance.

Will

COVID-19 trigger global political change?

There

are two reasons why it might. The first is that unlike "shocks" such

as war, earthquakes and famines, pandemics do not discriminate by geography or

human identity. By nature, pandemics are inclusionary, rendering borders

futile, and requiring global responses that are inclusionary in turn. Secondly,

unlike other security crises that preceded it - the World wars and regional

wars caused by the Uniteed States - governments will be unable to use the

spread of Covid-19 to silence opponents, since it will be harder to label

criticism in these cases as disloyal or unpatriotic. This will make regimes vulnerable

to leadership change, and offer an opportunity to marginalised political

parties to innovate.

For democracies and autocracies alike, COVID-19 shall, should, ultimately be a moral reckoning in the conduct of foreign and domestic policy, as nations' ability to grapple with the challenges of inequality, climate change and social mobility will stand exposed for all to see. Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan has already called on the global north to write off the debt of vulnerable countries. Whether or not that happens, government functionaries will certainly be held accountable for lack of regulation, commitment to social equity, and sufficiently deep cross-border engagement that preceded the disaster. And if and when the storm subsides, new norms will likely be needed to dictate how states behave with each other.

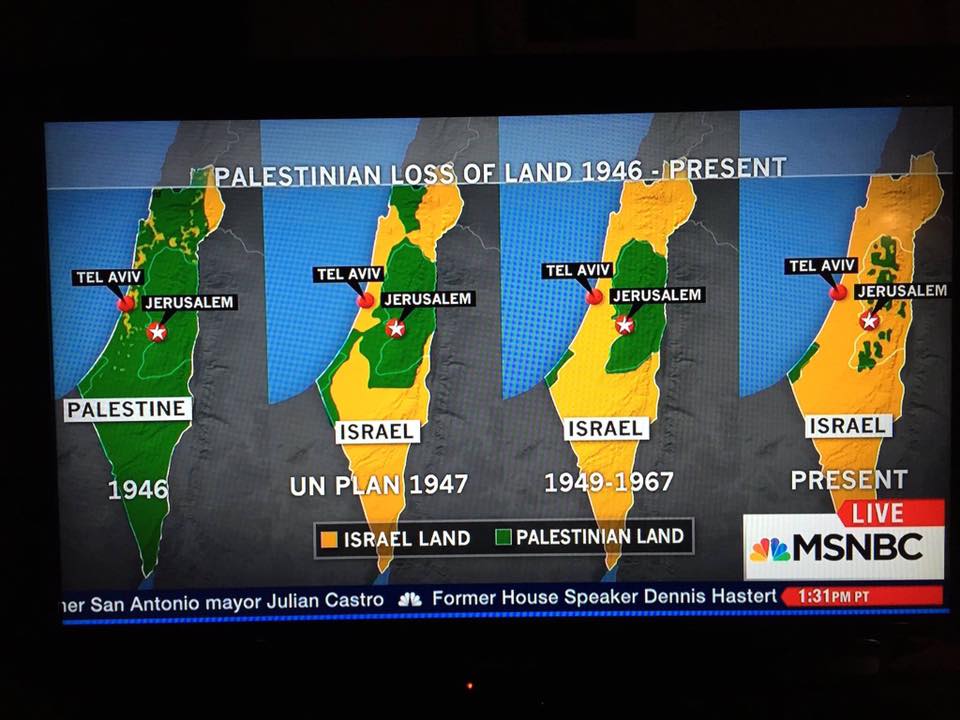

PALESTINA

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário