Even by climate change's destructive standards, water is in an increasingly grim bind.

Droughts and monster floods are having devastating effects on the human civilisation, as the situations in much of Africa, Australia, and China attest. Water shares per capita continue to drop, particularly in places where there is little, to begin with. From rising sea levels to fast-disappearing glaciers, and hurricanes of unprecedented strength, water is headlining many of the planet's most pressing problems.

And that is just the global picture. Many of the projections in the developing world make for even more unsettling viewing. Jordan could run out of water within a few decades, as could many small Pacific and Caribbean island states. Cities like Cape Town, Chennai, and Sao Paulo have already signalled the possible future of some urban areas - no water at all.

This is what a devastating water crisis looks like, but you would not know it by the global response. The focus is not there. At the climate summit in New York in September, there was a big push to transform food production systems and stem biodiversity loss, but water was barely mentioned. The Paris Climate Agreement all but ignored water, while the Global Commission on Adaptation, an ambitious new initiative to combat climate change, only included a water chapter after fierce lobbying. Time and again, water is passed over or given a lesser billing than the likes of agriculture or forestry at the negotiating table.

Crucially, the coordination is not there, either. That lack of attention at the very top is pushing water down the pecking order among regional, national, and local authorities, and in so doing, it is crushing momentum at every level. In practical terms, this means water is grossly undervalued from national capitals right down to smalltown district centres just as climate change wreaks havoc with our already energised water cycle. For all the lip service paid to water's importance - and the magnitude of its problems, water sometimes seems to get platitudes, statements of concern, but little in the way of concrete, life-saving policy prescriptions.

There is a bitter and unfortunate irony to all of this, of course. Though water is fundamental to everything and everyone, it is increasingly hostage to our deeply fragmented political climate. Water seldom respects borders, which makes interstate and intercommunal cooperation, and information sharing all the more necessary. With less and less of that going around, water and its roughly 7.7 billion dependents are becoming mired in paralysis that benefits no one. Given that most people either have or soon will first experience climate change through water, that is a tragedy.

But this crisis - and our reaction to it - also speaks to the obstacles the water community faces in rallying around an issue of this size and significance. Because of water's ubiquity, we have divvied up responsibility for its component "parts" among different organisations over the years - water for humans, water for agriculture, water for nature - so there is no powerful body capable of championing its cause.

The net result is that our key resource lacks the stature to fight its own corner at a time when messy politics is hamstringing action across the board. To put it bluntly, people are dying from climate-related catastrophes because our mechanisms for collaboration are not up to scratch.

Perhaps the greatest shame of all, though, is that many of these crises could just as easily be opportunities for progress. We know what can and should be done, just as we know well the consequences of a failure to act.

Residents of flood-prone megacities, like Lagos and Mumbai, should not have to put their lives on hold and weather inhospitable and sometimes deadly conditions every time extreme rainfall strikes. But until water institutions are empowered and infrastructural investment unleashed, millions of people will stew in floodwaters, sometimes for months at a time. To compound this madness, improved urban water access could yield a trillion-dollar economic boost, instead of billions in losses.

Farmers, too, need not lose everything whenever vicious and increasingly frequent droughts hit, but until water receives the focus it warrants, we will have insufficient resources and clout to build resilience among the planet's poorest people across South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Middle East. For example, introducing simple technologies for capturing floodwaters to recharge underground resources can help farmers endure these long dry spells.

Introducing technologies, such as satellite data and monitoring from sensors which help farmers irrigate only when crops require water by informing them of soil moisture rates, requires the kind of political buy-in that we often lack. At the very least, we can deploy early warning systems, and thereby ensure that the local authorities - and the people who depend on them - meet disasters with maximum preparation.

Morocco, for example, has already taken such measures in its parched deep south. It has enacted a law that helps manage the movements of traditional agro-pastoralists during droughts to ensure grazing areas are not over-stressed and damaged.

There are no one-size-fits-all solutions, but through policy and regulatory reforms, improvements to governance, and the use of nature-based tools alongside digital technology, we have an array of answers.

And unless greater emphasis is placed on improving global water governance, we risk undoing whatever climate action we have engineered so far, while also missing out on a golden opportunity to deliver potentially seismic changes elsewhere.

It is really no coincidence that water insecure states tend to be politically and economically fragile as well. It is our contention that improved water management can be a catalyst for superior state-wide governance and treatment of women and marginalised communities. From Yemen to northern Nigeria, Syria, Pakistan and many places in between, we are desperate to turn water from a source of tension and misery to a basis for development and cooperation.

Even in an optimistic scenario, there will be no preventing some of the damage climate change will wreak. The threats are too many and water too enormous a resource to completely shield. But contrary to some of the more dispiriting news coverage, there are solutions out there. We just need to mobilise the international community to deploy them.

At the ongoing climate change conference in Madrid, we have another opportunity to resurrect climate action, and it is our firm belief that if this gathering is to succeed where previous ones failed, we are going to have to put water front and center. Its all-consuming nature makes it a fitting focal point for us to coalesce around. Its deadly toll leaves us no choice.

As tens of millions of people currently battle deadly floods in Central Africa, the Horn of Africa and parts of Europe, and many millions more face horror drought in Southern Africa, Eastern Australia, and China, the message ought to be clear: forget water at your peril.

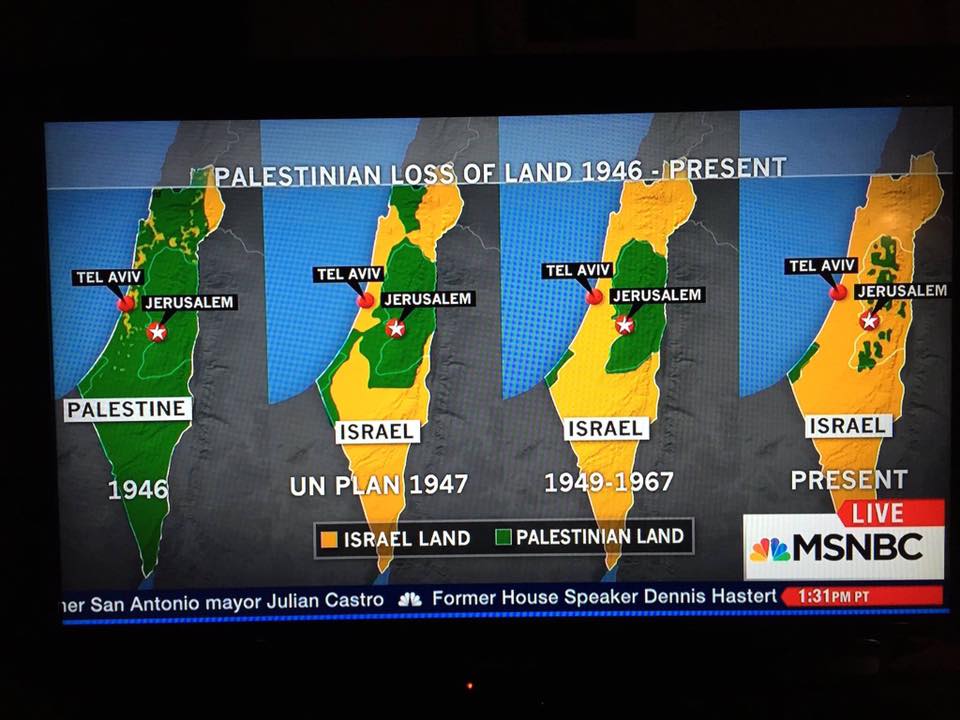

PALESTINA

Total water resources in the Midlle East region are made up of two componets - surface water and groundwater. The main surface-water resource is the Jordan River Basin, with the Sea of Galilee as the major regional water reservoi. >it has a storage capacity of 4.000 million cubic meters (mcm) znf trvrives an average annual replenishment of about 840cm. The Yarmuk River is also an integral part of the >Jordan River Basin. Its headwaters join the <jordan River 10km below the Sea of Galilee.

Groundwater is the most important source of freswater supply in the area, and consists of the main West Bank aquifer systems, as well as the Gaza Strip aquifer. Around 600mcm of the annual rainfall ins estamated to infiltrate the soil to replenish the aquifers and about 40mcm of rain each year percolâtes to recharge the coastal aquifer underlying Strip.

Israel currently has control over a major part of the Jordan Basin waters.

Israel, Syria and Jordan abstract 450mcm from the Sea of Galilee. This reduces the downstream Jordan to a fetid trickle.

In Gaza, growndwater is the only source of fresh water, with an estimated potential of 65mcm per year. At present, though, the aquifer is being over-pumped (100mcm annually), in quantities exceeding the replenishment rate, resulting in the gradual invasion of seawater.

Following its occuptaion of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in 1967, Israel implemented stringent policies that prevented Paletinians from fully utilizing the West Bank's groundwater. These include the expropriation of wells belonging to Palestinian farmers, the denial of permits for the drilling of wells , and the imposition of rigorous water quotas.

In sum, due to restrictions on water allocation imposed by israel, the water situation in Palestine is approaching a critial phase that hinders economic development and threatens the livelihood of the Plaestinian population. It is clear that an apportionment of water rights between the conflicting parties should be considered on a more equitable basis.

A serious discrepancy exists between the amount of water supplied to Palestinians as compared to Israelis. While a Palestinian uses on average 70-150 cubic meters (cm) /year, an Israeli uses 370cm/year. Such discrepancy is not limited to water quantities, but extends to water pricing as well. Israelis pay $0.16 per cm for agricultural water; whereas Palestinians pay a standard rate of $1.20 for piped water.

A re-allocation of this vital resource between the two sides is possible and imperative. However, Israel is doing the opposite. The Palestinians in the West Bank are in bad shape, but in Gaza its even worse.

WHO indicated that 97 per cent of water pumped from Gaza’s aquifer, which is depleting at a rapid rate, fails to meet the minimum standards of quality for potable water.

In fact, the very sustainability of the Gaza Strip’s basin is now in jeopardy. WHO findings further confirm a previous United Nations report that Gaza could become uninhabitable by 2020, which is, next year.

Alas, it appears that this is to be the horrific reality for Gaza.

The occupied West Bank is not much better off as Palestinians are denied access to their own water resources. They are unable to dig new wills in most of the West Bank, forbidden from utilising Jordan River water and are forced to purchase nearly a quarter of their own water from Israel.

This is completely unacceptable and runs contrary to international law.

Free access to water is a basic human right.

A protracted discussion on water as a human right culminated in a UN General Assembly resolution, 64/292 of July 28, 2010. It explicitly “recognises the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights.”

It all makes perfect sense. There can be no life without water. But like every other human right, Palestinians are denied that as well.

Total water control was one of the first policies enacted by Israel after the establishment of the military regime following the occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza in June 1967.

Israel's discriminatory policies can be described as water apartheid.

Excessive Israeli water consumption, erratic use of dams and denying Palestinians the right to thei own water has resulted in vast and possibly irreversible environmental conséquences, fundamentally altering the aquatic ecosystem altogether.

In the West Bank, Israel uses water to cement existing Palestinian dependency on the very Israeli occupation.

Israel uses a cruel form of economic dependency to keep Palestinians reliant and subordinate. This model is sustained through the control of borders, military checkpoints, collection of taxes, border closures, military curfews and denial of building permits.

Water dependency is a centrepiece in this strategy

The "Interim Agreement of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip", known as the Oslo II Agreement signed in September 1995, crystallised the unfairness of Oslo I, which was signed in September 1993. Over 71 per cent of Palestinian aquifer water was made available for Israeli use and only 17 per cent for Palestinian use.

More appallingly, the new agreement invited a mechanism that forced Palestinians to buy their own water from Israel, further cementing the client Relationship between the Palestinian Autority (PA) and Israel.

The Israeli water company, Mekorot, a government-owned company, misuses its privileges to reward and punish Palestinians as it sees fit.

In the summer of 2016, entire Palestinian communities in the West Bank went without water as the PA failed to pay Israel massive sums of money to purchase back Palestinian water.

Palestinians in the West Bank use about 72 litres of water per person per day, compared to 240-300 litres for Israelis.

According to Oxfam, “less than four per cent of freshwater (in Gaza) is drinkable and the surrounding sea is polluted by sewage”. Oxfam researchers concluded that water pollution is dangerously linked to a dramatic increase in kidney problems in the Gaza Strip.

The US-based RAND Corporation found that one-fourth of all diseases in the besieged Gaza Strip are waterborne.

Gaza hospitals are trying to fight the massive epidemic while being underequipped, suffering power cuts and themselves lacking clean water.

"Water is frequently unavailable at Al-Shifa, the largest hospital in Gaza,” the RAND report continues. “Even when it is available, doctors and nurses are unable to sterilise their hands to carry out surgery because of the water quality.”

These water policies are mere facets in a much larger war against the Palestinian people to reinforce Israel’s colonial control.

While much attention has been rightly given to the military aspect of the Israeli occupation, Israel’s colonial policies involving water, receive far less attention yet are crucial.

It is a pressing and critical problem, however, that must be addressed and remedied as Gaza is being slowly poisoned while the West Bank is victimised by an ongoing water apartheid.

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário