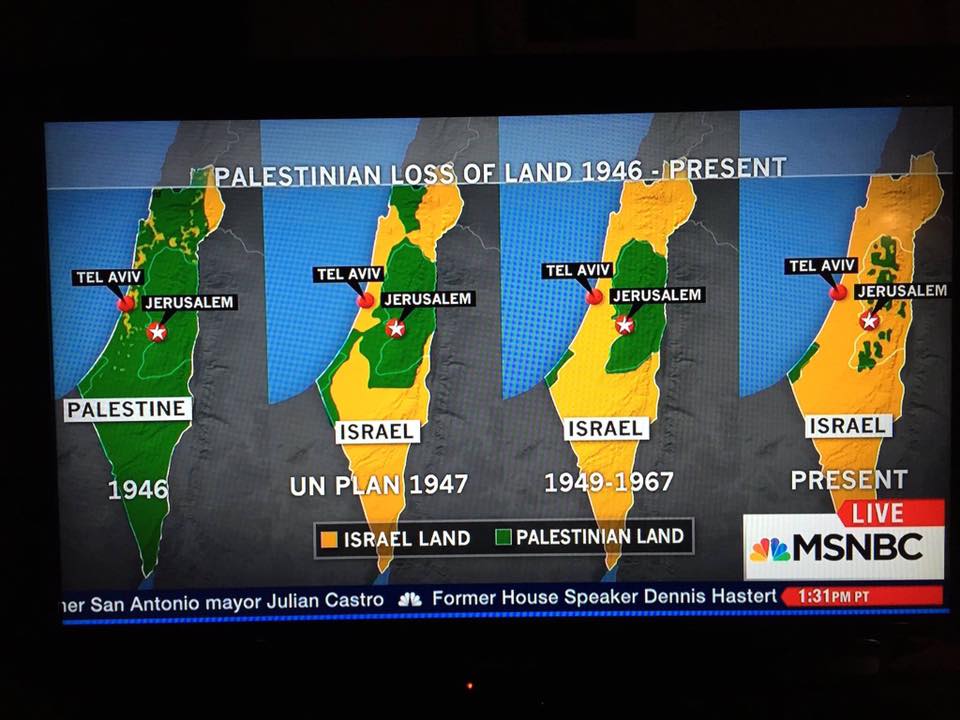

Let's not forget the beginning of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine

I'm not sure the news of the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the founder and leader of ISIS or ISIL or Daesh and the self-declared caliph of Islamic State is a reason for gloating.. He was already weak and losing his aura, just as bin Laden at the time he was murdered. Therefore, there could be a younger leader ready to step up to give another turn to the terrorist movement. His death is a hard, though not terminal, blow to the ferocious jihadi movement he has headed since 2010.

The place where he was located by Russian intelligence – in the Barisha area north of Idlib city in northwest Syria, close to the Turkish border – came as a surprise to the USA. It was assumed that he was hiding somewhere in the desert in the Syrian-Iraq border region where the remnants of Isis still have some bases.

Isis has not had direct control in the Idlib region for several years and it is rival jihadi groups, supposedly hostile to Isis, who rule an extensive region centred on Idlib province. It is possible that Baghdadi, who has only survived for so long through rigorous security measures, chose his final hiding place there for this very reason.

Even though he was in deep hiding for so long, Baghdadi remained the symbol of his Islamic State and his survival, despite intense efforts to find him and kill him, has demonstrated hitherto that Isis still possess an organisation able to keep him safe. His death is evidence that this is no longer the case, though it will be able to continue as a guerrilla force. It will be aided in this by the increased chaos on the ground following the US partial pullout from Syria, the Turkish invasion and the Kurds being forced to shift towards some form of alliance with Damascus.

Baghdadi remains a mysterious figure in death as in life because it has never been clear to what degree the resurgence of Isis – known previously as al-Qaeda in Iraq and Islamic State in Iraq (ISI) – after 2011 was his doing.

His real name was Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Samarrai and he was born into a pious Sunni Arab family in Samarra, north of Baghdad, in 1971. Imprisoned and tortured by US forces in 2004, he was not considered a significant resistance figure and was released after ten months.

He became leader of ISI in 2010 after the death of his predecessors in a US airstrike. At the time the movement had retreated to its areas of core support in and around Mosul and to rural regions where al-Qaeda in Iraq had always been strong. It retained more strength than its many enemies realised and had plenty of military experience drawn from the 2004-9 war against the US and Iraqi government forces.

The Arab Spring uprisings in 2011, notably in Syria, presented Baghdadi and ISI with an opportunity for swift expansion as the Syrian government lost control of large parts of the country. Al-Baghdadi sent seasoned militants and fighters, money and weapons to establish Jabhat al-Nusra as the leading rebel organisation, though its dependence on ISI was at first kept secret.

The link between the two was only revealed in 2013 when al-Baghdadi tried to reassert his authority over al-Nusra, which had been highly successful in spreading its rule in Syria. When part of al-Nusra rejected this, Baghdadi deposed its leaders, fought an inter-jihadi civil war and later broke with al-Qaeda, establishing Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Isis).

In Iraq, Baghdadi was fortunate in his opportunities as the Sunni Arab community was increasingly alienated by a sectarian Shia government which ignored or suppressed its protests. The Iraqi army and security forces were degraded by extreme corruption and the weeding out of competent commanders.

Even so, the world was astonished when Isis captured Mosul in June 2014 and Baghdadi named himself caliph of the newly-founded Islamic State. A hundred days of runaway victories by Isis forces in Iraq and Syria followed, its fighters advancing against little resistance to Tikrit, north of Baghdad, and to Palmyra, east of Damascus.

As Isis fighters established a state which, at its greatest extent, was the same size as Great Britain, they massacred Shia and Yazidis, publicising their atrocities by video. The purpose of this savagery was extreme sectarianism combined with a determination to spread terror among its opponents and sap their will to resist.

This ferocious cruelty towards all those not supporting the Islamic State was typical of al-Baghdadi’s rule: the world was divided into light and darkness and only Isis stood in the light. This approach was effective in motivating fanatical Isis fighters but ensured that everybody outside Isis was a satanic enemy to be destroyed. Eventually, the caliph was at war with the whole world – Syrian government and Syrian opposition, Russia and the United States, Turkey and Saudi Arabia. He may have led Isis to great and unexpected victories, but he also ensured its defeat.

His military forces – essentially skilled light infantry supplemented with the mass use of suicide bombers – were outgunned and outnumbered. In 2014, the separatist Kurds in Iraq and Syria would have preferred to stay neutral, but Isis attacked them anyway. This brought in the US as a combatant and Isis’s military forces were relentlessly targeted by the air power of the US-led coalition. Its last victories were won in 2015, when it took Ramadi in Iraq and Palmyra in Syria but after that the caliphate was battered to pieces by superior forces over the following two years.

Baghdadi is believed to have escaped from Mosul during a surprise attack on besieging forces from inside the city in early 2017, but his location was always elusive. The decisive military defeat for Isis came later the same year with the fall, after long sieges, of Mosul and Raqqa. Baghdadi made occasional recorded inspirational addresses but had no answer to the crumbling of his caliphate other than to encourage terror attacks on civilian targets abroad from Manchester to Colombo.

He was repeatedly reported to be dead or injured but would re-emerge, most recently in a video this Apri - we shall wait and hope he will not emerge from the rubbes once more. Isis was reverting to a guerrilla role, hoping to repeat its extraordinary resurrection between 2011 and 2014. But the fear that Isis had inspired at the height of its success meant that governments were unlikely to be caught by surprise a second time. It also seemed inevitable, once Isis had lost its last territory earlier this year, that Baghdadi could not evade his pursuers forever.

The making of al-Baghdadi's doings was American, as always - thus, unfortunately, he might not be the last head of the hydra.

At the height of the al-Qaeda-led insurgency in Iraq in 2006-07, US commanders, whose troops were suffering serious casualties from roadside bombs, developed a strategy. They sought to identify, kill or capture the leaders of the cells planting the Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in the belief that this would cripple the bombing campaign.

Many such high-value targets were tracked down and eliminated, but the whole strategy turned out to be misconceived and counterproductive. A study of 200 cases of cell leaders being killed or arrested in 2007 showed that in the month following the elimination of the individual targeted, the number of IED attacks in the area where his cell operated actually increased by between 20 and 40 per cent.

This was happening because al-Qaeda had assumed that its local military leaders would have a low survival rate and always had a replacement ready to take over within 24 hours of his demise. These new commanders were eager to show their military prowess by making more attacks, while their predecessor had often suffered from battle fatigue or was short on new ideas about how to carry the fight to the enemy. A theory well explained on Andrew Cockburn’s book Kill Chain: Drones and the Rise of High-Tech Assassins.)

But there is another less reassuring way of looking at the killing of Baghdadi. It may do more harm than good because he was a demonstrably disastrous leader from the point of view of his own movement. By effectively declaring war on all the world he led it to certain defeat and his elimination may be just what Isis needs to rejuvenate itself. As with those al-Qaeda bomb makers in Iraq a dozen years ago, a new Isis leader may be more dangerous because he will avoid Baghdadi’s gargantuan mistakes, relaunching the movement in a different guise and with different ways of operating.

Isis, with Baghdadi as its leader, had certain strengths: religious fanaticism wedded to military expertise, making it a formidable fighting force. It proved powerfully attractive to the persecuted Sunni Arab populations of Iraq and Syria living under challenging governments that they hated.

But under Baghdadi those same Sunni Arabs found that they were living under a nightmarish tyranny where the pettiest religious or social transgression was punished by beatings and executions. It was a state ruled by fear. For all its brutality discipline, the Islamic State was unable to defend its inhabitants against their enemies or prevent the ruin of their cities and towns.

But Isis could have taken a different course – and almost did so – when its Syrian affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra took a less bloodthirsty and more flexible approach in expanding its rule between 2011 and 2013. Baghdadi promptly tried to take it over, split the movement, and ensured that the territory he controlled was true to his brutal theological vision of an Islamic state.

With Baghdadi at its head, Isis was never going to rise again, but with him out of the way it may stand a better chance of doing so in Syria and Iraq. In both countries some of the ingredients that led to the astonishing resurgence of Isis in 2011-14 are beginning to recur: the Iraqi government is grappling with protests close to a popular uprising, successful army commanders are being fired, and the Sunni Arabs are marginalised and impoverished. In northeast Syria, the successful Kurdish-US alliance against Isis is broken while Turkish and Syrian government forces are moving into the region. It is this sort of chaos in which a remodelled Isis might take root and flourish.

The death of Baghdadi may have more impact on the Isis franchises in other parts of the world where his prestige as the caliph was often greater than in the territories he ruled. Religious movements often make it easier to revere a dead martyr than a demonstrably fallible live one.

Political and military leaders around the world pretend that the decapitation of some hostile organisation or movement will solve all problems. But how much did the 1993 killing of Pablo Escobar, the Colombian cocaine king, really change anything in the cocaine business? It just worsened it.

Donald Trump's self-congratulatory gloating over the death of Baghdadi may turn out to be equally misplaced.

The making of al-Baghdadi's doings was American, as always - thus, unfortunately, he might not be the last head of the hydra.

At the height of the al-Qaeda-led insurgency in Iraq in 2006-07, US commanders, whose troops were suffering serious casualties from roadside bombs, developed a strategy. They sought to identify, kill or capture the leaders of the cells planting the Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in the belief that this would cripple the bombing campaign.

Many such high-value targets were tracked down and eliminated, but the whole strategy turned out to be misconceived and counterproductive. A study of 200 cases of cell leaders being killed or arrested in 2007 showed that in the month following the elimination of the individual targeted, the number of IED attacks in the area where his cell operated actually increased by between 20 and 40 per cent.

This was happening because al-Qaeda had assumed that its local military leaders would have a low survival rate and always had a replacement ready to take over within 24 hours of his demise. These new commanders were eager to show their military prowess by making more attacks, while their predecessor had often suffered from battle fatigue or was short on new ideas about how to carry the fight to the enemy. A theory well explained on Andrew Cockburn’s book Kill Chain: Drones and the Rise of High-Tech Assassins.)

But there is another less reassuring way of looking at the killing of Baghdadi. It may do more harm than good because he was a demonstrably disastrous leader from the point of view of his own movement. By effectively declaring war on all the world he led it to certain defeat and his elimination may be just what Isis needs to rejuvenate itself. As with those al-Qaeda bomb makers in Iraq a dozen years ago, a new Isis leader may be more dangerous because he will avoid Baghdadi’s gargantuan mistakes, relaunching the movement in a different guise and with different ways of operating.

Isis, with Baghdadi as its leader, had certain strengths: religious fanaticism wedded to military expertise, making it a formidable fighting force. It proved powerfully attractive to the persecuted Sunni Arab populations of Iraq and Syria living under challenging governments that they hated.

But under Baghdadi those same Sunni Arabs found that they were living under a nightmarish tyranny where the pettiest religious or social transgression was punished by beatings and executions. It was a state ruled by fear. For all its brutality discipline, the Islamic State was unable to defend its inhabitants against their enemies or prevent the ruin of their cities and towns.

But Isis could have taken a different course – and almost did so – when its Syrian affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra took a less bloodthirsty and more flexible approach in expanding its rule between 2011 and 2013. Baghdadi promptly tried to take it over, split the movement, and ensured that the territory he controlled was true to his brutal theological vision of an Islamic state.

With Baghdadi at its head, Isis was never going to rise again, but with him out of the way it may stand a better chance of doing so in Syria and Iraq. In both countries some of the ingredients that led to the astonishing resurgence of Isis in 2011-14 are beginning to recur: the Iraqi government is grappling with protests close to a popular uprising, successful army commanders are being fired, and the Sunni Arabs are marginalised and impoverished. In northeast Syria, the successful Kurdish-US alliance against Isis is broken while Turkish and Syrian government forces are moving into the region. It is this sort of chaos in which a remodelled Isis might take root and flourish.

The death of Baghdadi may have more impact on the Isis franchises in other parts of the world where his prestige as the caliph was often greater than in the territories he ruled. Religious movements often make it easier to revere a dead martyr than a demonstrably fallible live one.

Political and military leaders around the world pretend that the decapitation of some hostile organisation or movement will solve all problems. But how much did the 1993 killing of Pablo Escobar, the Colombian cocaine king, really change anything in the cocaine business? It just worsened it.

Donald Trump's self-congratulatory gloating over the death of Baghdadi may turn out to be equally misplaced.

UpFront 23/11/2018 : What happened to ISIL?

And Donald Trump did gloat, on Sunday, when he announced that the leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant ISIL or ISIS), Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, had been killed in a clandestine operation executed by US special forces in northwest Syria - without mentioning that it was possible with a big help from Russian intelligence.

Trump thanked the governments of Russia, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, as well as the Syrian Kurds, for lending support to the US authorities, but took the credit alone, which doesn't bother Vladimir Putin. The Russian President does not need to make believe he is strong.

The killing of al-Baghdadi, which came just two weeks after Trump ordered the US military to withdraw its forces from Syria could, therefore, be seen as the virtual end of the five-year US campaign against ISIL.

Given the circumstances under which the US is leaving the Middle East, however, it is doubtful that this would mean the end of the armed group. In fact, Trump might be on his way to making the same mistake his predecessor, President Barack Obama, did in 2010.

Although Trump has been blaming Obama for all the ills and mishaps of US policies in the Middle East - which is true - he is, in fact, following in his footsteps. In 2009, Obama came to power on the promise of bringing US troops "back home" and making up for US military blunders in the Islamic world.

He ordered US troops to pull out from Iraq by the end of 2011, claiming that al-Qaeda had been defeated and that the Iraqi government was fit to take control. The murder of Osama bin Laden in May 2011 helped Obama silence critics, especially at the Pentagon, who favoured a longer timetable for withdrawal.

In 2013, al-Qaeda returned in a more brutal incarnation under the ISIL flag. In June 2014, it sent shockwaves across the region when it defeated the US-trained Iraqi army and captured Mosul, Iraq's second-largest city. A couple of days later, from the pulpit of Mosul's famous al-Nuri Mosque, Baghdadi declared the formation of a caliphate.

The fall of Mosul, the defeat of the Iraqi army and the seizure of US-made equipment, including 2,300 Humvee armoured vehicles, was a major blow to the Obama administration, which found itself forced to dispatch US troops back to Iraq. A US-led international coalition to destroy ISIL was formed in September 2014.

Five years later, Trump declared that ISIL was "100 percent" defeated in Syria and that he is ready to bring US troops back. Just as Obama was, the current president is mainly concerned about fulfilling an election promise.

To avoid creating a vacuum and silence critics, Trump accepted an offer made during a phone call on October 6, 2019, with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to take over the battle against ISIL in Syria.

The agreement with Turkey created more problems than it solved. The president was attacked by both Democrats and Republicans for "selling out" his Kurdish allies, who fought and died alongside US forces in the war against ISIL.

To contain the storm, Trump sent his vice president to Ankara to negotiate an end to the Turkish operation. On October 17, the US and Turkey reached an agreement wherein Turkey, according to a White House briefing, agreed "to pause its offensive for 120 hours to allow the United States to facilitate the withdrawal of YPG forces from the Turkish-controlled safe zone". Article five of the agreement stated also that "Turkey and the US are committed to fighting ISIS/DAESH activities in northeast Syria".

It is striking that al-Baghdadi was located and killed in northwest Syria near the Turkish borders 10 days after the Pence-Erdogan meeting in Ankara. It also came less than a week after the October 22 Erdogan-Putin summit in Sochi, wherein the two leaders agreed to push back Kurdish fighters from a "safe zone" along the Turkey-Syria border and emphasised "their determination to combat terrorism in all forms and manifestations".

It is believed that Turkey and Russia may have played a key role in locating al-Baghdadi and in sharing intelligence with the US in order to help President Trump justify his decision to withdraw from Syria. For completely different reasons, both countries have a vested interest in making the US pull out of Syria.

ISIL has lost all of the territories it once controlled in Syria and Iraq. Thousands of its die-hard fighters have been eliminated. The killing of al-Baghdadi must have also been a big blow.

Yet, as in the past, these losses are unlikely to lead to the dissolution of the group because the underlining circumstances that gave rise to it are still intact.

First, the Levant continues to be the battleground of regional rivalries, which destabilise the region and leave space for ISIL to stage a comeback. Right now Russia, Turkey and Iran, the key players in the Syrian conflict, all want the US to leave Syria but this consensus may not last after the US withdrawal.

Iran already feels that it is being excluded from the understandings between Russia and Turkey on one hand, and the US and Turkey, on the other hand.

In fact, Iran fears that the new arrangements in northern Syria, wherein Turkey and Russia try to fill in the vacuum resulting from the departure of US troops, will be at its expense. Ankara and Moscow may well be working towards preventing Tehran from establishing a "Shia crescent" across east Syria, which both the US and its closest ally Israel fear.

To complicate things even further, the Pentagon decided to keep the Syrian oil fields under US control. Oil income, according to Secretary of Defence Mark Esper, will help fund Kurdish fighters, including the ones guarding prisons that hold captured ISIL fighters. The Syrian regime cannot survive in a post-conflict environment without recovering the oil fields too.

Turkey will interpret the US move as a step towards creating a local economy for a possibly independent Kurdish entity in east Syria. Russia will not tolerate that either. This means renewed turmoil in northeast Syria is quite likely.

Second, the maladies which plague Arab countries and which ISIL exploited to recruit and expand, are still very much present. Sectarian politics in the Middle East are still raging across the Middle East, marginalising various communities; social-economic problems, like poverty, corruption, injustice, repression, etc have still not been resolved.

If these conditions are not dealt with, ISIL will no doubt make a comeback, just as al-Qaeda did in the past.

To help defeat ISIL once and for all, an international effort is needed to establish security and end conflict. We need to establish a regional security system - something like OSCE in Europe - that would address the security concerns of all the states in the region, stop regional rivalries, proxy wars and interference in the internal affairs of other states.

We also need to find a just solution to the conflict in Syria that would include both transitional justice and national reconciliation. We also need to establish more egalitarian and more representative political systems in the Arab world that could effectively tackle the most pressing socioeconomic ills.

Only then can ISIL be defeated, not only as a group but more importantly as an idea, and only then can the US withdraw from the region without creating a security vacuum that allows for armed insurgencies to re-emerge and terrorise the local population.

Inside Story: Will ISIL outlive its leader?

PALESTINA

Apartheid Adventures

Ao visitar o patrimônio cristão na Cisjordânia e na Palestina histórica, por favor, não se hospede nas colônias ilegais nem nas casas tomadas dos palestinos em Haifa durante a Nakba.

A new report shows that Airbnb profits from human rights abuses not just in illegal Jewish-Zionists settements on stolen Palestinian land in the West Bank, but also in places like the Old City of Yaffa where it lists properties that were stolen from Palestinian families in 1948. Check it out

BRASIL

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário