When Palestinians launched the Great March of Return on March 30, Israel sensed an opportunity for confrontation. It started sniping down one unarmed protester after the other while blasting propaganda about how these Palestinians constituted a "threat" to its security and how it had the "right to defend itself".

To date, Israeli soldiers have killed 135 peaceful Palestinian protesters. But the Israelis did not stop there.

As international public opinion swung dangerously against them, the Israeli occupation forces began to respond to the peaceful demonstrations by targeting armed resistance groups in Gaza, bombing their training grounds, arms storage, tunnels and logistics capabilities, as well as assassinating several of their members.

The Israeli army had no justification for these attacks; it simply wanted to enforce a new reality on the ground: That peaceful resistance would be met with brute force and any escalation would be followed by a broader military assault.

After some deliberation, a military response was launched from Gaza. Many within the armed resistance groups were convinced that Israel should not be allowed to impose this new reality on the ground and should be shown that there will be a response to its military assaults.

What this episode shows, however, is that it is increasingly difficult for Israel to maintain the status quo. Its strategy of "Gaza will not live and will not die" no longer seems to be working. It fears

that small improvements and patches will no longer appease the Palestinians.

And it is in this context that Israel seems to face three options in Gaza: reoccupation, another war, or lifting of the siege.

There have been some voices of the extreme right in the Israeli government, military and intellectual elite who have been calling for a reoccupation of Gaza. They believe that establishing military control over the Strip again could remove the threat it poses.

They call for taking over the entire Strip with troops on the ground and carrying out a comprehensive eradication operation against Gaza's armed groups. After that is fulfilled, Gaza would supposedly be handed over to a third party, such as the Palestinian Authority or an international body, to address and administer the humanitarian needs of the population.

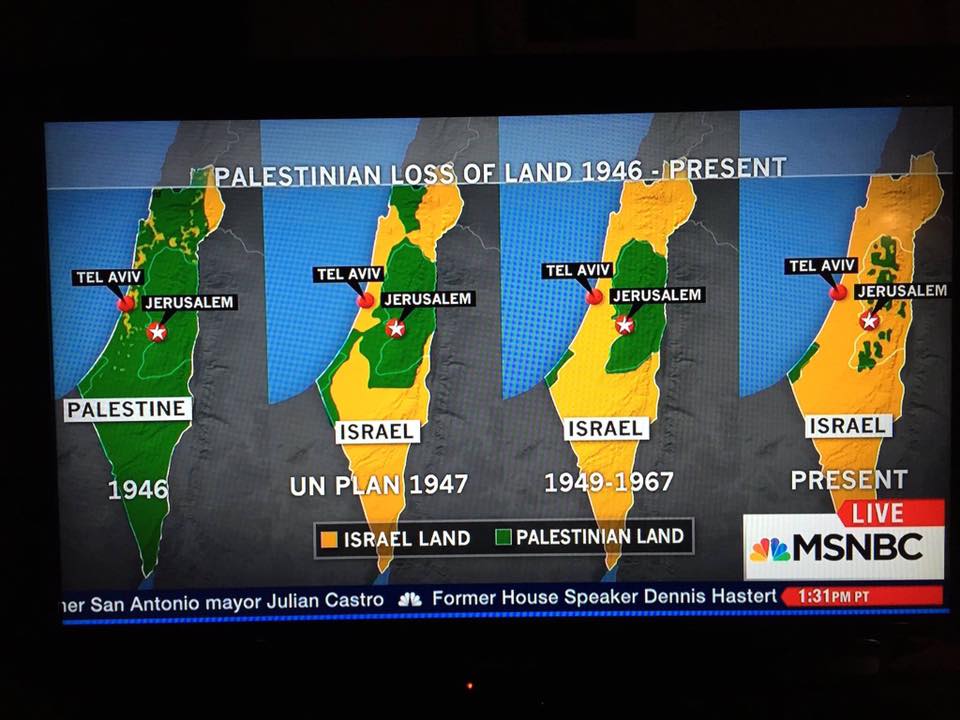

pals

Those who advocate for this solution know full well that they are looking at a bloody disaster. Israel will undoubtedly meet severe resistance in Gaza which would lead to dozens, if not hundreds of Israeli soldiers killed. There is nothing more painful for Israel than to have its soldiers return from the battlefield in black body bags.

If it reoccupies the Strip, the Israeli state will then have to provide the minimum level of food, water and electricity to the economically exhausted population. That would put a heavy strain on the government budget.

The death toll that such a military operation would exact on Gaza's civilian population would mean a harrowing defeat on the international stage for the Israeli narrative. International outrage at Israeli crimes is growing day by day and it will eventually reach a breaking point.

It is important to mention here that this option is not very popular within Tel Aviv's decision-making circles, whether in the government, army or intelligence because they realise just how steep the price they would pay is.

Another major military assault on Gaza is the popular option with influential political and military figures in Israel as it is perceived to be less costly than reoccupying it. It seems to fulfil the urgent need to come up with a new deterrent against Hamas after its recent missile attacks on Israeli settlements near Gaza.

Israel has grown accustomed to launching an attack on Gaza every few years, as part of its "mowing the grass" policy. Whenever Hamas' capabilities - whether human or logistical - grow, a need arises to cut them back through air attacks or field assassinations that restore Israel's deterrent for a few more years.

After the several operations Israel launched between 2006 and 2014, it may well be about to launch another one. In spite of their conviction that this option is needed soon, high-ranking generals are leery of it because they know the Palestinian armed groups have rebuilt their capabilities and prepared their ranks over the past four years.

A war within Gaza would not be a picnic, but they see it as a necessary evil or a "no choice war".

Lifting the siege on the Gaza Strip economically and administratively is the only acceptable option. It would also include the construction of a seaport or airport under Israel's tight security control and international guarantees.

This option takes the burden of supporting Gaza's two million inhabitants off Israel's shoulders, but its strategic implications make the Israeli leadership shy away from it. It would make the creation of a Palestinian entity with state-like features feasible, without it having to present the customary "instruments of obedience" to Israel, as the West Bank does.

In addition, there wouldn't be enough guarantees that Hamas would not take advantage of these new port facilities to bring in weapons that may well upset the military status quo.

As the situation on the ground in Gaza changes and Israeli threats against Palestinians increase, all three options are possible. Israel will make its detailed calculations on each one of them, but in the end, developments on the ground will determine which way events unfold.

The people of Gaza have been subjected to decades of expulsion, occupation, siege and massacre. They have now seized control of their Fate. They are risking life and limb as they protest nonviolently to reclaim their basic rights. It takes just one minute to send a video showing your support for Gaza in its moment of truth. Do it now! Send your videos to metoogaza.com

Mr. Mladenov presented to the 15-member body the sixth quarterly report on the implementation of Council resolution 2334, covering the period from 26 March to 12 June this year.

“As detailed in the report, no steps were taken during the reporting period to “cease all settlement activities in the occupied Palestinian territory, including East Jerusalem’ as demanded by the resolution”, he said.

The July 2016 report of the Middle East Quartet – comprising the UN, Russia, the United States and the European Union – identified Israel’s ILLEGAL SETTLEMENT activity as one of the main obstacles to achieving a two-state solution, which is to establish a viable, sovereign Palestinian state that lives in peace and security with Israel.

In Tuesday’s briefing, Mr. Mladenov noted that some 3,500 housing units in settlements in what is known as “Area C” of the occupied West Bank had either been “advanced, approved or tendered”. One-third of those units are in settlements in outlying locations deep inside the West Bank.

Plans for 2,300 units were advanced in the approval process, while 300 units had reached the final approval stage. Tenders had gone out for about 900 units, he said. As in the previous period, no advancements, approvals or tenders were made in occupied East Jérusalem.

“I reiterate that all settlement activity is illegal under international law. It continues to undermine the practical prospects for establishing a viable Palestinian state and erodes remaining hopes for peace,” he said.

During the reporting period, Israeli authorities demolished or seized 84 Palestinian-owned structures, resulting in the displacement of 67 people and potentially affected the livelihoods of 4,500 others.

“I want to again reiterate the call of the Secretary-General on all to unequivocally condemn, in the strongest possible terms, all actions that have brought us to this dangerous place and led to the loss of so many lives in Gaza,” he said. Did anybody listen?

Donald Trump is quietly escalating America’s role in the Saudi-led war on Yemen, disregarding the huge humanitarian toll and voices in Congress that are trying to rein in the Pentagon’s involvement. Trump administration officials are considering a request from Saudi Arabia and its ally, the United Arab Emirates, for direct US military help to retake Yemen’s main port from Houthi rebels. The Hodeidah port is a major conduit for humanitarian aid in Yemen, and a prolonged battle could be catastrophic for millions of civilians who depend on already limited aid.

With little public attention or debate, the president has already expanded US military assistance to his Saudi and UAE allies – in ways that are prolonging the Yemen war and increasing civilian suffering. Soon after Trump took office in early 2017, his administration reversed a decision by former president Barack Obama to suspend the sale of over $500m in laser-guided bombs and other munitions to the Saudi military, over concerns about civilian deaths in Yemen. The US Senate narrowly approved that sale, in a vote of 53 to 47, almost handing Trump an embarrassing defeat.

In late 2017, after the Houthis fired ballistic missiles at several Saudi cities, the Pentagon secretly sent US special forces to the Saudi-Yemen border, to help the Saudi military locate and destroy Houthi missile sites. While US troops did not cross into Yemen to directly fight Yemen’s rebels, the clandestine mission escalated US participation in a war that has dragged on since Saudi Arabia and its allies began bombing the Houthis in March 2015.

The war has killed at least 10,000 Yemenis and left more than 22 million people –three-quarters of Yemen’s population – in need of humanitarian aid. At least 8 million Yemenis are on the brink of famine, and 1 million are infected with cholera.

The increased US military support for Saudi actions in Yemen is part of a larger policy shift by Trump and his top advisers since he took office, in which Trump voices constant support for Saudi Arabia and perpetual criticism of its regional rival, Iran. The transformation was solidified during Trump’s visit to the kingdom in May 2017, which he chose as the first stop on his maiden foreign trip as president. Saudi leaders gave Trump a grandiose welcome: they filled the streets of Riyadh with billboards of Trump and the Saudi King Salman; organized extravagant receptions and sword dances; and awarded Trump the kingdom’s highest honor, a gold medallion named after the founding monarch.

The Saudi campaign to seduce Trump worked. Since then, Trump has offered virtually unqualified support for Saudi leaders, especially the young and ambitious crown prince Mohammed bin Salman, who is the architect of the disastrous war in Yemen. By blatantly taking sides, Trump exacerbated the proxy war between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and inflamed sectarian conflict in the region.

During his visit to Riyadh, Trump announced a series of weapons sales to the kingdom that will total nearly $110bn over 10 years. Trump, along with Jared Kushner, his son-in-law and senior adviser, who played a major role in negotiating parts of the agreement, were quick to claim credit for a massive arms deal that would boost the US economy. But many of the weapons that the Saudis plan to buy – including dozens of F-15 fighter jets, Patriot missile-defense systems, Apache attack helicopters, hundreds of armored vehicles and thousands of bombs and missiles – were already approved by Obama.

From 2009 to 2016, the Obama administration authorized a record $115bn in military sales to Saudi Arabia, far more than any previous administration. Of that total, US and Saudi officials signed formal deals worth about $58bn, and Washington delivered $14bn worth of weaponry.

Much of that weaponry is being used in Yemen, with US technical support. In October 2016, warplanes from the Saudi-led coalition bombed a community hall in Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, where mourners had gathered for a funeral, killing at least 140 people and wounding hundreds. After that attack – the deadliest since Saudi Arabia launched its war – the Obama administration pledged to conduct “an immediate review” of its logistical support for the Saudi coalition. But that review led to minor changes: the US withdrew a handful of personnel from Saudi Arabia and suspended the sale of some munitions.

Toward the end of the Obama administration, some American officials worried that US support to the Saudis – especially intelligence assistance in identifying targets and mid-air refueling for Saudi aircraft – would make the United States a co-belligerent in the war under international law. That means Washington could be implicated in war crimes and US personnel could, in theory, be exposed to international prosecution. In 2015, as the civilian death toll rose in Yemen, US officials debated internally for months about whether to go ahead with arms sales to Saudi Arabia.

But these concerns evaporated after Trump took office. Like much of his chaotic foreign policy, Trump is escalating US military involvement in Yemen without pushing for a political settlement to the Saudi-led war. His total support for Saudi Arabia and its allies is making the world’s worst humanitarian crisis even more severe.

Cross Talk: Destruction of Yemen

Inside Story: Can global Community act on sexual torture claims in Yemen prisons?

PALESTINA

Kites against drones

"Keys must always be the symbol of the Palestinian “Nakba” – the “disaster” – the final, fateful, terrible last turning in the lock of those front doors as 750,000 Arab men, women and children fled or were thrown out of their homes in what was to become the state of Israel in 1947 and 1948.

Just for a few days, mind you, for most of them were convinced – or thought they knew – that they would return after a week or two and re-open those front doors and walk back into the houses many had owned for generations. I always feel a sense of “shock and awe” when I see those keys – and I held one in my hand again a few days ago.

It was a heavy key, rather like the big iron keys for big iron locks that Britons and Americans used more than a hundred years ago, with a long wide shaft, a single bit and a bow – where you hold the key – with a slight double-curve at the bottom so that you can grip it firmly between two fingers and thumb.

The farmer who owned this key lived in the Palestine border village of Al-Khalisa and locked up his home – built of black basalt stones – for the last time on 11 May 1948, when the Jewish Haganah militia refused the villagers’ request to stay on their land.

Israeli and Palestinian historians have agreed on the history of the village. Today, al-Khalisa is the Israeli frontier town of Kiryat Shmona, and the few refugees who remain alive in the squalid camps of Lebanon can still see their lands if they travel to the far south of the country and look across the border fence.

Few camps could be more vile than the slums of Chatila, where Mohamed Issi Khatib runs his equally shabby “Museum of Memory” in a hovel adorned with ancient Palestinian farm scythes, photocopies of British and Ottoman land deeds, old 1940s radio sets and brass coffee pots – and keys. Just three of them. One, without even a proper bit, was probably used for an animal shed.

The Khatib family lost their own key (the one I held belonged to the grandfather of a refugee called Kamel Hassan). Mohamed was born in Lebanon, just after his parents fled al-Khalisa, and a few days before the independence of the new state of Israel was declared.

The UN General Assembly Resolution 194 of 1948 says the Arabs should return to their homes; hence the continued Palestinian demand – justified but hopeless – for a “right of return” to their own lands, which are now part of Israel.

Israel’s Absentee Property Law of 1950 denies the return of any Arabs who fled their property during the Israeli independence war. Many Israelis agree that the Arab dispossession was unjust. But as the fine and liberal Israeli scholar Avi Schlaim once told me, Israel was admitted to membership of the UN in 1949. “What is legal is not necessarily just,” he said.

This is not an argument you can put to Mohamed Khatib, who worked until his retirement 10 years ago as a doctor for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, set up in 1949 to look after Palestinian refugees from the “Nakba”, and later for those who fled or were driven from their homes in the 1967 Middle East war.

It cares for around 5 million Palestinians – many of them children and grandchildren of the 1947-8 refugees, born in exile, almost half a million of them in Lebanon.

Khatib’s museum of wretchedness smells of cigarette smoke – not everyone there was abiding by the Ramadan fast before I arrived (which they cheerfully admitted), and there is a faint odour of rust and old paper.

Mohamed Issi Khatib worked until his retirement as a doctor for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (Duraid Manajim).

The documents and brown passports are familiar to me. Over the years, I’ve read through similar papers, land deeds and passports, usually surmounted by the crest of Mandate Palestine’s British “protectors”, that familiar crown, lion and unicorn, and the imprecation honi soit qui mal y pense – “may he be shamed who thinks badly of it”. Khatib blames Britain us for the Palestinian disaster, and points to the keys. “You did this,” he says, smiling in complicity because we all know the history of the 101-year old Balfour Declaration, which declared Britain’s support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine, but referred to the majority Arab population as “existing non-Jewish communities”

But when I ask Khatib if he will ever return to his “Palestine” – a consummation which many Palestinians have in reality abandoned – he insists that he will, and explains his belief with a long and disturbing and quite chilling argument: that Israel is a “foreign body” in the region which cannot survive, which was implanted from outside.

He sounds, I tell him, like the former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmedinejad – a crackpot of Trump-like proportions in my view – and I conclude it must be goodbye to the two-state solution if this is how Arabs plan to regard their future neighbours. But Khatib says – rightly, I fear – that the early Palestinian desire for such a solution has long ago been abandoned in the face of Israeli violence.

So what, I ask, did the Palestinians do wrong in all these years? Didn’t they make any mistakes? “They did,” he says. “Their mistake was to leave, to go out of Palestine. They should have stayed [in 1947 and 1948]. Our fathers and grandfathers should have stayed, even if they felt themselves in danger, they should have stayed on their land even if they died. My mother said to me once: “Why did we leave? I should have kept you with me and stayed with you there.”

What a bitter conclusion. Many Palestinians did stay. But many others stayed and died – think Deir Yassin – at a time, just after the Second World War, when the West’s sensitivities were blunted by conflict and did not care if a few hundred thousand more refugees were put out of their homes. I understand Mohamed because parents do not always make wise decisions but, if I was in their shoes – holding my front door key – I’m not sure I would have stayed. Anyway, I would have thought I was only going away for a few days…

I’ve gone back to his parents’ “Palestine” many times, taken some old keys with me to Israel – the locks had been changed, of course – and knocked on the front doors of those Arab houses that remain, and talked to the Israeli Jews who now live in them. One expressed his sorrow for the former Palestinian owner and asked me to pass on his feelings to him, which I did.

Another, an old Jewish man originally from a city in southern Poland, a Holocaust survivor who had been driven from his home by the Nazis, his mother murdered in Auschwitz, drew me a map of where he and his parents once lived. I even travelled to Poland and found his old house and knocked on the front door, and a Polish woman answered and asked – as Israelis might ask if they thought the Arabs were going to reclaim their property: “Are they coming back?” Polish law gives former Jewish citizens the right to take back Nazi-confiscated property.

I acknowledge Mohamed Khatib’s need to remind the world what actually happened to the Palestinians. He asks me why I am “pro-Palestinian” and I reply that I am “pro-truth – but I am not pro-Palestinian”. I’m not sure if he understood the point. His parents’ house had three rooms with a stream beside it, he says. His father was a policeman for the British mandate. I Ieave him, though, with the feeling that history stretches out into the future as well as the past, that he will never return and that his little museum and its keys are a symbol of regret rather than hope". Robert Fisk

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário