As the cases and casualties of COVID-19 increase globally, medical professionals are deeply concerned not just about the virus itself, but also about the increasing anxiety and sheer fear people are experiencing as they try to deal with the pandemic.

As people around the globe are asked to self-isolate, practice social distancing, and altogether lead a hermetic life to help "flatten the curve" of human catastrophe, there is no doubt something in the very texture and disposition of the global village is changing, and changing rapidly.

A key question today is how to survive not just the pandemic itself, but to do so with a healthy and robust constellation of our mental, moral, creative and critical faculties.

Giovanni Boccaccio's 14th-century book The Decameron may give us a hint of how it can show us how to survive coronavirus.

Boccaccio wrote The Decameron in the wake of the plague outbreak in Florence in 1348 to guide fellow Italians on "how to maintain mental wellbeing in times of epidemics and isolation". The racy stories in the book are allusions to the power of storytelling to maintain robust mental health in a time of overwhelming anxieties. That meant protecting yourself with storie. Boccaccio suggested you could save yourself by fleeing towns, surrounding yourself with pleasant company and telling amusing stories to keep spirits up. Through a mixture of social isolation and pleasant activities, it was possible to survive the worst days of an epidemic. That sounds like a perfect recipe these days, too.

Boccaccio's novel has served other purposes in more recent years. The 1971 film The Decameron, based on Boccaccio's 14th-century masterpiece, was the first movie of Italian director Pier Paolo Pasolini's Trilogy of Life, which also included The Canterbury Tales and Arabian Nights. In his rendering, Pasolini remained fixated on the plight of humanity in the course of fascism and all its pathologies of power.

Later, in another deeply disturbing masterpiece, Salo, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), Pier Paolo Pasolini carried the same fears to their even more degenerate ends. Fascism and plague, or fascism as a plague, equally resonates with our age of xenophobic racism exemplified by United States President Donald Trump referring to COVID-19 as the "Chinese virus".

Even before Pasolini, similar themes preoccupied Albert Camus in his enduring 1947 masterpiece The Plague, where the Algerian city of Oran becomes the setting of his existential reflections on the effects of an allegorical pandemic on the human soul.

Camus brought together two disparate events, the cholera epidemic in Algeria in 1849 and the rise of European fascism, to reflect on the fragility of our lived experiences in times of collective frenzy. As a compelling allegory of the Nazi occupation of France and beyond, Camus used references to mass burials as an allusion to the concentration and extermination camps in Nazi Germany. There was, and there remains a powerful allegorical potency to the very idea of a plague.

Even earlier, in 1882, Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen also explored similar sentiments in his play An Enemy of the People. Something in the power of storytelling or staging at one and the same time alerts and frightens and yet paradoxically comforts and reassures. Were such temptations not behind Gabriel Garcia Marquez's 1985 novel Love in the Time of Cholera, too?

In the time of Covid-19, all such metaphors have morphed into reality. Films such as Wolfgang Petersen's Outbreak (1995) and Steven Soderbergh's Contagion (2011) have now become prophetic if not apocalyptic.

But equal to Pasolini taking Bocaccio's The Decameron to fascist ends, or Camus or Ibsen, a poem of Sa'di Shirazi coming about a century before Boccaccio drew my mind. Every Iranian schoolchild knows these powerful opening lines of this major poem by heart:

A famine of such devastation one year happened in Damascus

That lovers forget all about love . . .

The rest of the poem describes in exquisite detail the calamity that had befallen Syria where it had not rained for a long time, gushing springs had all dried out, no kitchen emitted any smoke of cooking, old widows were in despair, surrounding hills were dried of all vegetation, orchards bore no fruits, the locusts were eating the crops and people were eating the locusts.

The poetic persona of Sa'di then comes across a friend who has lost much weight. He asks him why is he so weak, as he is a wealthy man and should have weathered the famine much better. Then comes the most memorable punchline of the poem:

The wise man looked at me visibly hurt,

With the look of a wise man upon an ignoramus:

I am not weak because I don't have food to eat,

I am saddened because of the sufferings of the poor!

We read this poem of Sa'di today with two immediate feelings: first the beauty and elegance of his poetic diction, the power of his imageries, the brevity with which he conveys so much across generations and worlds, and second, the towering moral voice that he sustains about the social duties of the mighty and powerful.

I thought of this poem of Sa'di as I ventured out to do a bit of shopping in Paris, where we are asked to self-isolate as much as possible, facing row after row of empty shelves, looted by a frightened and cruel population that lacks the slightest sense of civic duty towards their elders and more vulnerable neighbours, let alone able to fathom the vision and the wisdom of a "democratic socialism".

But how precisely are we to survive this pandemic with a sense of common decency? Long before this pandemic began, in 2012, Jonathan Jones wrote a cogent piece for The Guardian, Brush with the Black Death: how artists painted through the plague, in which he explains how "from 1347 to the late 17th century, Europe was stalked by the Black Death, yet art not only survived, it flourished." Towards the end of his essay, Jones concludes: "Human beings have a shocking resilience. They also have the power to rise above self-pity. If that does not seem obvious today, just consider St Paul's, serene in the London sky, a message to us from an age of everyday heroism."

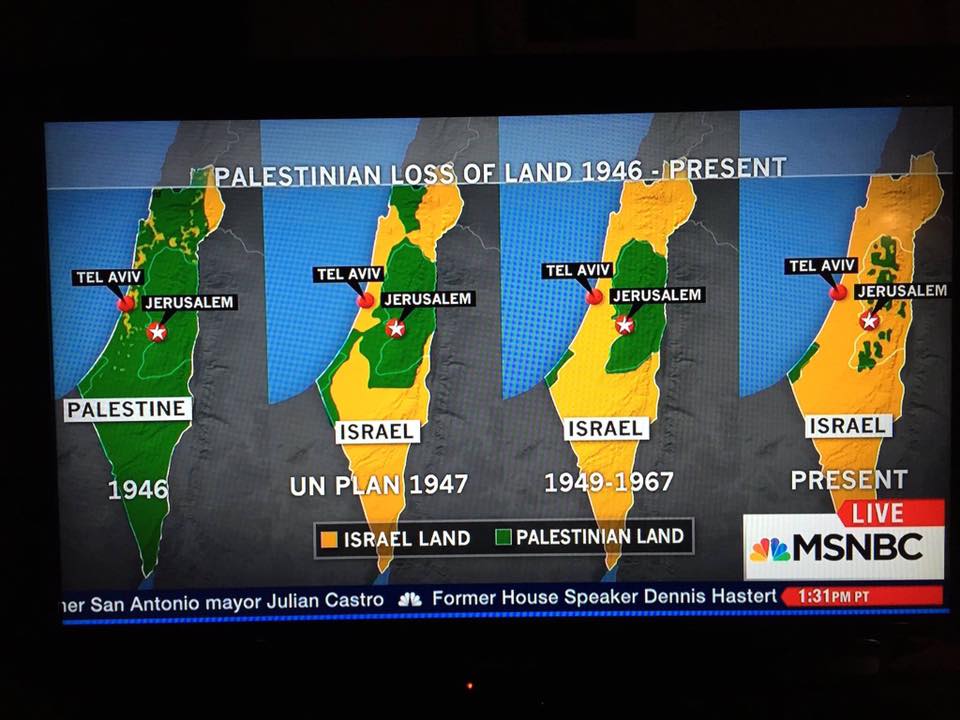

But do we? One silver lining of the coronavirus pandemic our planet faces today is that all the dividing lines of East and West, South and North, rich and poor, powerful and powerless, are erased. Donald Trump is today as scared of a handshake as those brave physicians at the front line of fighting the virus are vulnerable. And physicians are not even the only heroes of this human tragedy. Even more courageous than them all are the Paletinians, emprisoned in their own land, every single mother who has to keep her beloved children inside an overcrowded home without enough water and enough food to feed them. They might starve to death before coronavirus gets them. Or the 5.000 Palestinian political prisoners in Isralei jails today, who sent a humanitarian appeal to the world Calling to save them from the Deadly coronavirus pandemic before it kills them.

You, I, we are among the lucky ones who are confined in nice house or appartements, with money to buy food when we can go out, order a delivery, read a book, watch series and movies on Netflix, or concerts, operas and ballets on Arte or elsewhere. Let's not complain, be brave and helf whoever and however we can our families, neighbours and comunities.

Surviving this pandemic is urgent but not sufficient, surviving it with a sense of common decency, collective reasoning, solidarity and public purpose is equally important.

Whilst the Covid -19 haunts hospitals and homes all over the continents, the White House continues to ravage the Middle East with its mischiefs.

First it was his sly retreat from Iraq; now it’s his cosy military exercises with the United Arab Emirates – famous in song and legend as a former Saudi ally in the bloody Yemen war – and his cut of $1bn in aid to Afganistan because its presidential feuding may hamper another deal with his newly established chums in the Taliban. And then there’s Iran...

So let’s look for a moment at the extraordinary mock city built in the Emirates – complete with multi-storey buildings, hotels, apartment complexes, an airport control tower, oil refineries and a central mosque – which Emirati troops and US Marines have been assaulting with much clamour in a joint military exercise. According to the Associated Press reporter who watched this Hollywood-style epic, Emirati soldiers rappelled from helicopters while Marines “searched narrow streets on the Persian Gulf for mock-enemy forces”.

But who were these “forces”? Iranian, perhaps? In which case, the mock-mosque was presumably Shia, the oil refineries presumably in southern Iran, and the old streets in one of Iran’s ancient cities. Surely not Shiraz. Surely not Isfahan.

Brigadier General Thomas Savage of the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force didn’t seem to think the Iranians might find all this a bit suspicious. The exercise – Operation Native Fury, the name of which seemed to carry its own colonial message – is held every two years. “Provocative?” asked the aforesaid Savage. “I don’t know. We’re about stability in the region. So if they view it as provocative, well, that’s up to them. This is just a normal training exercise for us.”

I’m not at all sure that it’s “normal” for American armed forces to stage make-believe attacks on scale-model Muslim cities complete with mosque and narrow streets in order to create “stability in the region”. Surely this particular mock-up was not intended to stand in for Yemeni cities, around which Emirati troops had been fighting for four years against pro-Iranian Houthi fighters before turning against their Saudi allies in the same conflict and doing a quick bunk. The 4,000 US troops had been sent into the Emirates from Diego Garcia and Kuwait, where they might have recently arrived from the three newly abandoned American bases in Iraq. General Savage said none of his men had tested positive for the coronavirus and have “had little contact with the outside world” since shipping out for the exercise.

In a different context, Trump, who also has little contact with the outside world – the real one, that is – has been back to blackmailing his allies “in the region”. While much of that world continues to obsess about imminent pestilential death, the US secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, has suddenly – and with very little publicity — cut $1bn in aid to Afghanistan and threatened further reductions in cooperation. This is a bitter blow for a nation also facing Covid 19 (we can probably dismiss the handful of declared cases and two deaths there as an absurd underestimation), but America comes first!

Trump and Pompeo, you see, are very, very angry that both Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah both claim to have been elected president in the recent elections – thus endangering the agreement between Washington and the Taliban to withdraw all US forces in return for the Taliban’s promise to fight Isis, al-Qaeda and all other jihadis wandering around Afghanistan. The signed understanding between the US and what I suppose we must call “Talibanistan” also includes a mutual exchange of prisoners (5,000 of the Taliban for 1,000 government troops) to which both of the rival presidents object.

Abdullah and Ghani, who was once described by his old university in Beirut as a “global thinker”, appear to have forgotten the words of the Persian medieval poet Saadi: that while 10 poor people could sleep on a carpet, two kings could not fit into a single kingdom.

You can see why Pompeo is upset. Not since rival popes – and, I suppose, earlier rival Roman emperors – simultaneously announced their supremacy have we witnessed such a pairing of panjandrums. If Afghanistan is the graveyard of empires, it is also the font of hubris for its local masters – who, with their palaces, villas, bodyguards and 4x4s will not be affected by the cut in aid. If the two men were to reach a resolution to their dispute, Pompeo has announced, the US sanctions will be “revisited” – proving that this is indeed a spot of blackmail by Trump.

But US sanctions are clearly not going to be “revisited” in relation to Iran, which claims – not without some justice – that the ban on imports is hindering its own struggle against Covid-19.

The UN has called for such sanctions to be “urgently re-evaluated”, pointing out that human-rights reports have already described the malign effect of sanctions on Iran’s access to respirators and protective clothes for healthcare workers. The Iranians, with the declared number of cases above 27,000 and more than 2,000 confirmed deaths, may have covered up many more victims – and this, remember, is a regime that couldn’t tell the difference between a Ukrainian airliner and an American cruise missile (and lied about it for two days). They clearly need help. American sanctions, however, matter more than the coronavirus in the Middle East.

So, alas, does Iranian amour propre. With truly Trumpian fantasy – for the US president still calls the virus “Chinese” – Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, inspired it seems by a Chinese official’s comments, has suggested that Covid-19 was man-made in America and that US medicine “is a way to spread the virus more”. This sort of claptrap is on a level with former Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who claimed that a halo shone over his head at the UN and that his listeners didn’t blink for half an hour while he spoke. “You [Americans] might send people as doctors and therapists; maybe they would want to come here and see the effect of the poison they have produced in person,” announced the 80-year-old divine.

After this nonsense, Imran Khan, the Pakistani prime minister, was perhaps the only regional leader who could still appeal to the US to lift the sanctions on “humanitarian grounds” until the virus has receded. Needless to say, he was wasting his time.

And finally, a US Marine Osprey V-22 helicopter took off from the US embassy compound in Beirut last week, carrying aboard Amer Fakhoury, a former member of Israel’s proxy South Lebanon Army militia. Fakhoury, now a US citizen, had returned to Lebanon last September to visit his family – he was met at Beirut airport by a senior army officer – but was recognised by former prisoners as an ex-warden at Israel’s notorious Khiam jail. He was immediately accused by the Lebanese authorities of torturing inmates and brought before a military tribunal.

Fakhoury denied, and still denies, all the charges against him. He was subsequently released when a judge said the crimes levelled against him occurred more than 10 years ago. Fakhoury, who entered hospital in Beirut suffering from stage 4 lymphoma, had fled across the border after Israel’s retreat from Lebanon in 2000. An appeal was lodged against his release by a military judge, but Fakhoury was nonetheless flown out of Lebanon. “We’ve been working very hard to get him freed,” Trump said, which is true: a US embassy official insisted on attending the military court last year when Fakhoury made his first appearance.

Khiam prison was infamous for the torture and mistreatment of Shia Muslim prisoners – both male and female. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch published numerous and detailed reports of torture at the jail, and The Independent also published eyewitness accounts of torture. Fakhoury’s release prompted an outburst of fury from Lebanese parties who believed that their government had acted under threat of economic sanctions from Washington.

There were even claims that the Hezbollah militia, paid and armed by Iran, had been involved in discussions over Fakhoury’s release with a representative of the Trump administration. Its leader, Sayed Hassan Nasrallah, in a rare burst of anger, denied such a conspiracy.

Of course, scarcely anyone saw the departure of Lebanon’s most famous prisoner. For as the American helicopter lifted him to freedom over the Mediterranean, Beirut’s inhabitants were hiding in their homes to avoid catching Covid-19.

PALESTINA

Imagine um lugar onde 1.820.000 pessoas estão presas em 365km² sob "dieta" de uma média de 75 calorias não proteicas diárias, carente de água e medicamentos devido a um bloqueio militar aérero, marítimo e terrestre imposto desde 2006.

Imagine agora o coronavirus golpeando esse povo oprimido e enclausurado sendo golpeado pelo coronavirus. Este lugar se chama Gaza.

As the number of infections and deaths from COVID-19 multiply by the day, there have been increasing calls across the world for people to show solidarity and care for each other. Yet for the Israeli government, there is no such thing as solidarity.

As soon as the first coronavirus infections were detected, the Israeli authorities demonstrated that they have no intention of easing apartheid to make sure Palestinians are able to face the epidemic under more humane conditions.

Repression has continued, with the Israeli occupation forces using the excuse of increased police presence to continue rads on some communities, such as the Issawiya neighborhood in East Jerusalem, home demolitions in places like Kafr Qasim village and the destruction of crops in Bedouin communities in the Naqab desert.

Despite four Palestinian prisoners testing positive for COVID-19, the Israeli government has so far refused to heed calls to release the 5,000 Palestinians (including 180 children) that it currently holds in its jails. And there has been no sign that the debilitating siege on the Gaza Strip, which has decimated its public services, would be lifted any time soon.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is also trying to exclude the mostly Palestinian Joint List from the formation of an emergency unity government to tackle the outbreak, calling its members "terror supporters".

At the same time, the Israeli authorities have been quick to depict Palestinians as carriers of the virus and a threat to public health.

In early March, when the Palestinian Ministry of Health announced it had confirmed the first seven cases of the coronavirus (which causes COVID-19 disease) in the occupied Palestinian territory, Israeli Defense minister Naftali Bennett was quick to shut down the city of Bethlehem, where all the cases were located.

Of course, the concern there was not the health and safety of Palestinians in the city, but rather the threat of them infecting Israelis. The nearby settlement of Efrat - which also had confirmed infections, of course - was not put on lockdown at that time.

Shortly after, the health ministry issued a statement advising Israelis not to enter the occupied Palestinian territories.

Then last week, Netanyahu asked the "Arab-speaking public" to follow the instruction of the ministry of health saying that there is a compliance problem among the Palestinians. No such concerns were expressed about of some members of the Jewish population of Israel, who outright refused to shut down religious schools and businesses.

This attitude towards Palestinians is of course not new. The writings of early European Zionist settlers are full of racist assumptions about Arab hygiene and living conditions, and the threat of the disease coming from the Palestinian population was an early justification for apartheid.

Apart from the decades-old repression and discrimination, during the COVID-19 epidemic, Palestinians will be facing another consequence of occupation and apartheid - a broken healthcare system.

The roots of its dysfunction go back to the mandate era, when the British discouraged the formation of a Palestinian-run healthcare sector. The Palestinian population (mostly the urban parts of it) was serviced by a number of hospitals that the British colonialists set up, as well as health facilities established by various Western missionaries. Meanwhile, the Jewish settlers were allowed to set up their own healthcare system, funded generously from abroad and run independently of the mandate.

During World War II, some missionaries left and closed down their clinics, and after 1948, the British withdrew, leaving behind an ill-performing healthcare infrastructure. In 1949, Egypt annexed Gaza. The following year, Jordan did the same with the West Bank. Over the next 17 years, Cairo and Amman provided for the Palestinian population living under their rule, but they did not really establish a well-functioning healthcare system.

UNRWA - the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East - had to step up its services, providing primary healthcare, while the Palestinians started building a network of charitable healthcare facilities.

After the war of 1967 and the Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, Israel as an occupying power was legally responsible for healthcare of the Palestinians, but unsurprisingly, it did nothing to encourage the development of a robust healthcare sector. To illustrate the point: in 1975, the budget allocated for healthcare in the West Bank was smaller than that of one Israeli hospital for the whole year.

In 1994, the Palestinian Authority was created and took over service provision. Needless to say, the continuing occupation and the fact that the Authority's budget was dependent on foreign donors and the whims of the Israeli government, as well as the corruption of PA officials, did not allow the Palestinian health sector to improve.

As a result, if you were to enter a Palestinian hospital in the West Bank today, you would be struck by the overcrowding of patients, the shortages of supplies, the inadequate equipment and the substandard infrastructure and sanitation. Medical professionals have repeatedly protested the poor working conditions in their hospitals, most recently in February this year, but to no avail.

With just 1.23 beds per 1,000 people, 2,550 working doctors, less than 20 intensive care specialists and less than 120 ventilators in all public hospitals, the occupied West Bank is facing a public health disaster if the authorities do not contain the spread of COVID-19.

The situation in the West Bank may seem bleak, but the one in the Gaza Strip is simply catastrophic. The United Nations announced that the strip will be unlivable by 2020. It is now 2020 and the residents of the Gaza Strip - apart from inhuman living conditions - are now also facing a COVID-19 outbreak, as the first cases were confirmed on March 21.

The Israeli, Egyptian and PA-imposed blockade of Gaza has brought its healthcare system to the brink of collapse. This has been compounded by cycles of destruction of health facilities and a slow rebuilding efforts following repeated large-scale military offensives by the Israeli military.

The people of Gaza already face dire conditions: unemployment is at 44 percent (61 percent for the youth); 80 percent of the population is dependent on some form of foreign assistance; 97 percent of water is undrinkable; and 10 percent of children have stunted growth due to malnutrition.

Healthcare provision is on a constant decline. According to the NGO Medical Aid for Palestinians, since the year 2000 "there has been a drop in the number of hospital beds (1.8 to 1.58), doctors (1.68 to 1.42) and nurses (2.09 to 1.98) per 1,000 people, leading to overcrowding and reduced quality of services". Israel's ban on the import of technology with possible "dual use" has restricted the purchasing of equipment, such as X-ray scanners and medical radioscopes.

Regular power cuts threaten the lives of thousands of patients relying on medical apparatuses, including babies in incubators. Hospitals lack about 40 percent of essential medicines, and there are inadequate amounts of basic medical supplies, such as syringes and gauze. The 2018 decision of the Trump administration to stop US funding for UNRWA also affected the agency's ability to provide healthcare and bring doctors to perform complex surgeries in Gaza.

The limits of the Gaza healthcare system were tested in 2018 during the March of the Great Return, when Israeli soldiers opened mass fire on unarmed Palestinians protesting near the fence separating the strip from Israeli territory. In those days, hospitals were overwhelmed with wounded and dead, and for months they were struggling to provide proper care for the thousands injured by live ammunition, many of whom were permanently disabled.

The Gaza Strip is one of the most densely populated areas in the world, which also experiences severe problems with water and sanitation infrastructure. It is clear that stopping COVID-19 from spreading will be next to impossible. It is also clear that the population, which is already worn down by malnutrition, a higher rate of disability (due to all the Israeli assaults), and psychological distress due to war and hardship will be that much more vulnerable to the virus. Many will die and the healthcare system will likely collapse.

So as the West Bank and Gaza face potential health catastrophes amid an impeding COVID-19 epidemic, the question is, what will Israel do? Will it give access to its healthcare system to Palestinians? Will it at least stop blocking foreign medical aid?

A recent video that went viral on Palestinian social media can give us the answer. In it, a Palestinian labourer is seen struggling to breathe by the side of a road at an Israel checkpoint near Beit Sira village. His Israeli employer had called the Israeli police on him after seeing him severely sick and suspecting that he had the virus. He had been picked up and dumped at the checkpoint.

Decades of settler colonial rule, military occupation, and repeated deadly assaults have taught Palestinians not to expect any "solidarity" from the Israeli apartheid government. In this, like in previous crises, they will pull through with their proverbial sumud (perseverance).

BRASIL

"Admitir que uma pessoa que aplaude torturadores seja nosso presidente porque fará reformas econômicas necessárias é como levar os filhos a um pediatra sabidamente pedófilo porque é um médico competente".

"Admitir que uma pessoa que aplaude torturadores seja nosso presidente porque fará reformas econômicas necessárias é como levar os filhos a um pediatra sabidamente pedófilo porque é um médico competente".Diante da pandemia do covid 19 que segue matando mundo afora e no Brasil, parece evidente que deter Bozonaro não é uma questão partidária nem ideológica de Esquerda vs Direita e sim uma questão de sobrevivência.