Continued genocide, struggle and mayhem in Palestine, increasing bloodshed in Kashmir, mass protest in Hong Kong - how can we connect these dots? Are they related?

Well, of course: The sun never set on the Union Jack! In the sunset of that empire - as is inevitable for all empires - chaos and turmoil were destined to follow.

"The world is reaping the chaos the British Empire sowed," Amy Hawkins recently wrote in Foreign Policy, "locals are still paying for the mess the British left behind in Hong Kong and Kashmir." The author left out Palestine, chief among places around the globe, where the British empire spread discord and enmity to ease its rule and prepare the ground for disaster after its exit.

Indeed, the anticolonial uprisings in the Indian subcontinent, China, the Arab world and elsewhere did not result in freedom or democracy for the nations ruled by the British Empire.

In Kashmir, the British left a bleeding wound amid the partition of colonial India.

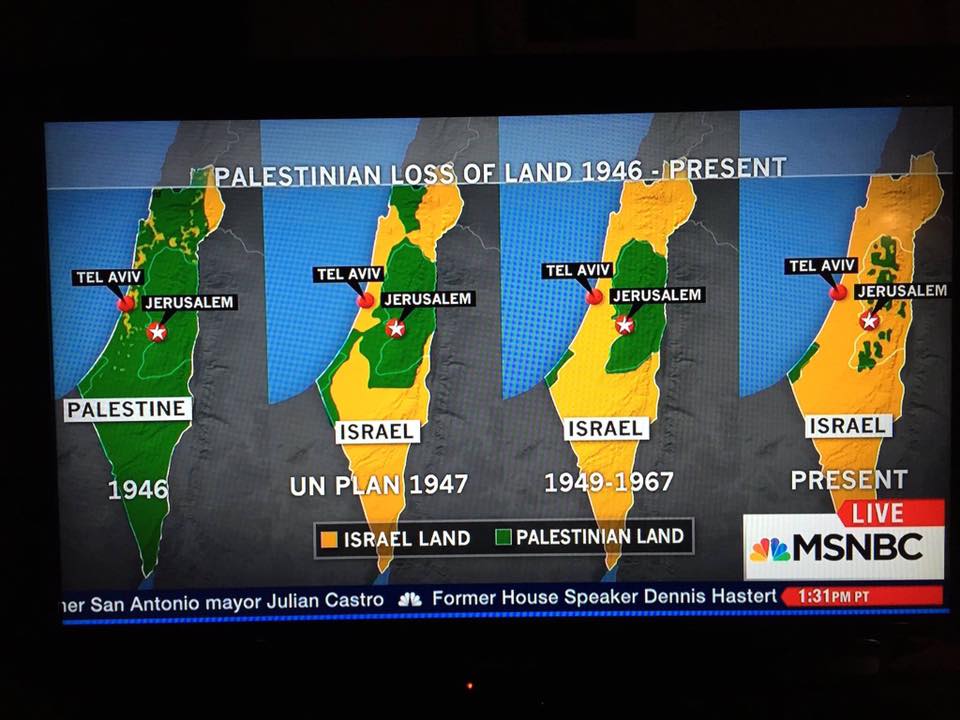

In Palestine, they left a European settler colony let call itself "Israel" to rule in "their" stead and torment Palestinians.

In Hong Kong, they left a major cosmopolis that is neither truly an independent entity, nor a part of mainland China.

They picked up their Union Jack and departed, leaving behind a ruinous legacy for decades and generations to bleed. Those consequences are not just historical and buried in the past. They are still unfolding.

Ironically, today the United Kingdom is struggling to hold itself together, as the Brexit debacle tears it apart. One looks at the country and marvels at the poetic justice of wanton cruelty coming back to haunt the former empire.

The UK finds itself face to face with its imperial past, with the Irish and Scottish once again defying English nationalists and their schizophrenic belief in their own exceptionalism. How bizarre, how just, how amazing, how Homeric, is that fate!

We may, in fact, be witness to the final dissolution of the "United" Kingdom in our life-times. But there was a time when, from that very little island, they ruled the world from America in the west passing through South Africa to Asia and Australia in the east.

The terror of British imperialism - wreaking havoc on the world not just then but now as well - is the most historically obvious source that unites Hong Kong, Kashmir, and Palestine as well as the many other emblematic sites of colonial and postcolonial calamities we see around us today. But what precisely is the cause of today's unrests?

In Hong Kong, Kashmir, and Palestine we have the rise of three nations, "baptised" by fire, as it were - three peoples, three collective memories, that have refused to settle for their colonial lot. The harsher they are brutalised, the mightier their collective will to resist power becomes.

Britain took possession of Hong Kong in 1842 after the First Opium War with China. It transformed it into a major trading and military outpost, and insisted on keeping it long after its empire collapsed. In 1997, Britain handed Hong Kong over to China, conceding to the idea of a "one country, two systems" formula that allows for a certain degree of economic autonomy for Hong Kong. But what both China and Britain had neglected to consider was the fact that a nation of almost eight million human beings throughout a long colonial and postcolonial history had accumulated a robust collective memory of its own, which was neither British nor mainland Chinese - it was distinct.

Kashmir came under British influence shortly after Hong Kong - in 1846, after the British East India Company defeated the Sikh Empire that ruled the region at that time. A century later, Kashmir was sucked into the bloody partition of India and Pakistan in the aftermath of the British departure from the subcontinent, with both post-colonial states having a mutually exclusive claim on its territory. Here, too, what India and Pakistan forget is the fact that almost 13 million Kashmiris have had a long history of countless troublesome colonial and postcolonial experiences, making Kashmir fundamentally different from either one of them.

The same is the case with Palestine, which fell under British rule in 1920 after the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. Before the British packed their colonial possessions and left almost three decades later, they installed a successor settler colony in the form of a Zionist garrison state. Decades of unrelenting struggle against the barbarities of the British and the Zionists have left Palestinians in possession of one of the most courageous and steadfast histories of resistance to colonial domination.

In revolting against China, India, and Israel, these three nations in Hong Kong, Kashmir, and Palestine have become three nuclei of resistance, of refusal to let go of their homelands.

They have narrated themselves into a history written by powers who have systematically tried to erase them and their collective memories. "Homeland" is not just a piece of land. It is a memorial presence of a history.

Those memories, corroborated by an entire history of resistance to imperial conquest and colonial occupation have now come back to haunt their tormentors.

China, India, and Israel have to resort to naked and brutish violence to deny the veracity of those defiant memories, now evident as facts on the ground. In doing so, these powers have picked up where the British empire left off.

They too seek to terrorise, divide and rule, but by now those they try to subdue have mastered resistance; their struggle has outlived one imperial oppressor, it can surely survive another.

In other words, no amount of imperial brutality, settler colonialism or historical revisionism can make the distinct identities, memories and histories of these people disappear.

Today people in Palestine, Kashmir, and Hong Kong see themselves as stateless nations ruled with brutish military occupation. In the postcolonial game of state formation, they have been denied their national sovereignty.

The more brutally they are repressed and denied their sovereignty, the more adamantly they will demand and exact it.

Neither China in Hong Kong, nor India in Kashmir, nor Israel in Palestine can have a day of peaceful domination until and unless the defiant nations they rule and abuse achieve and sustain their rightful place in the world.

More so Israel, despite the ethinic cleansing Tel Aviv has been carrying on since 1948 succeeding the British violent repressions of Palestinian intifada against the theft of their home country, history and nationality.

As Kashmir is one of my favourite countries in the world in beauty and people's kindness, let us put the rogue and mean Israel aside for today and focus in India a bit. Nowaday, but also on history.

India agreed to hold a free and impartial plebiscite in the state. At a mass public rally in Srinagar in 1948, Nehru, with the towering Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah by his side, solemnly promised to hold a plebiscite under United Nations auspices.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s ascendancy received vituperative opposition not just from royalist elements, but also from Ladakh’s Tibetan Buddhists who were apprehensive about the sudden rise of a new Kashmiri Muslim elite and were particularly fearful of the implications of its land reform policies for the Buddhist clergy’s enormous private land-holdings in Ladakh. As the elected head of government Abdullah “pushed through a set of major reforms, the most important of which was the “land to the tiller” legislation, which destroyed the power of the landlords, most of whom were non-Muslims. They were allowed to keep a maximum of 20 acres, provided they worked on the land themselves: 188,775 acres were transferred to 153,399 peasants, while the government organized collective farming on 90,000 acres. A law was passed prohibiting the sale of land to non-Kashmiris, thus preserving the basic topography of the region.”

The new economic plan of the state, formulated and executed by Abdullah’s government, underlined cooperative enterprise as opposed to malignant competition, in keeping with Abdullah’s socialist politics, which implied the organization and control of marketing and trade by the state. This revolutionary economic agenda in a hitherto feudal economy enabled the abolition of landlordism, allocation of land to the tiller, cooperative guilds of peasants, people’s control of forests, organized and planned cultivation of land, the development of sericulture, pisciculture and fruit orchards, and the utilization of forest and mineral wealth for the betterment of the populace. Tillers were assured of the right to work on the land without incurring the wrath of exploitative creditors, and were guaranteed material, social and health benefits (Korbel [1954] 2002: 204). These measures signaled the end of the chapter of peasant exploitation and subservience, and opened a new chapter of peasant emancipation.

Sheikh Abdullah’s unsurpassed achievement during his years as the prime minister of J & K from 1948 to 1953 was the abolition of the exploitative feudal system in the agrarian economy. He was also responsible for the eradication of monarchical rule. A.M. Diakov, a Soviet specialist on India, wrote about the progressive and democratic policies adopted by Abdullah’s National Conference (NC): “After the Second World War, a national movement in Kashmir developed the program of doing away with the Maharaja, of turning Kashmir into a democratic republic, of giving to the people of Kashmir the right of self-determination.”

The Dogra monarchy was formally abolished in 1952, and the last monarch’s heir apparent, Karan Singh, was declared the titular head of state. Disregarding the attempts of the Indian government to ratify its authority in J & K, the UN Security Council passed a resolution in March 1951 reminding the governments and authorities concerned of the premises of the Security Council resolutions of 21 April 1948, 3 June 1948 and 14 March 1950, and the United Nations (UN) Commission for India and Pakistan resolutions of 13 August 1948 and 5 January 1949, according to which a final decision about the status of the state would be made in accordance with the wishes of its people expressed in a free and fair referendum held under the impartial auspices of the UN.

This resolution also determined that the convening of a Constituent Assembly as recommended by the general council of the “All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference,” and any decision that the Assembly might take and attempt to execute determining the political affiliation of the entire state or any part thereof, would be considered as not in accordance with the above principles and would therefore be disregarded .

When Sheikh Abdullah first voiced his unrelenting opposition to autocratic rule in the state, his political stance was applauded by some sections of the Indian press, which, by foregrounding his position, further brought it out of the catacombs of provincialism: “It is imperialism’s game to disrupt the great democratic movement led by the NC. . . . There is no doubt that the NC would defeat these disruptive efforts by placing in the forefront the issue of ending the present autocratic regime and establishing a fully democratic government in accordance with its program.” (Communist, October 1947, quoted in Krishen 1951: 3–4)

Despite the injunction of the Security Council, Abdullah and his organization convened a Constituent Assembly in 1951. The NC regime was faced with unstinting opposition in the Hindu-dominated southern and southeastern districts of the Jammu region. Disgruntled elements comprising officials in the former maharaja’s administration who had been divested of their authority by the installation of a democratic regime in the state, and Hindu landlords stripped of their despotism by the NC administration’s populist land reforms, founded an organization called the Praja Parishad in late 1947, which was at loggerheads with Abdullah’s regime since 1949 (see Bose 1997: 104–64).

Despite all the odds, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah sought to maintain Kashmir’s autonomous status. Tariq Ali makes an astute observation regarding Abdullah’s locus standi: If Sheikh Abdullah had allied himself with Pakistan, the Indian government and its troops would have been unpleasantly disarmed. But he considered the political and social ideologies of the Muslim League extremely conservative and was afraid that if Kashmir acceded to Pakistan, the Punjabi feudal lords who were at the helm of the ship of policy making in the Muslim League would hamper political and social progress. In order to prevent such an occurrence, Abdullah agreed to support the Indian military presence in the State provided under United Nations auspices in J & K.

The purportedly autonomous status of J & K under Abdullah’s government provoked the ire of the Hindu nationalist parties, which sought the unequivocal integration of the state into the Indian Union.

The unitary concept of nationalism that these organizations subscribed to challenged the basic principle that the nation was founded on, namely, democracy. In such a nationalist project, one of the forms that the nullification of past and present histories takes is the subjection of religious minorities to a centralized and authoritarian state buttressed by nostalgia of a “glorious past.”

The unequivocal aim of the supporters of the integration of J & K into the Indian Union was to expunge the political autonomy endowed on the state by India’s constitutional provisions.

According to the unitary discourse of sovereignty disseminated by the Hindu nationalists, J & K was not entitled to the signifiers of statehood – a prime minister, flag and constitution. The concept of nationalism constructed by Hindu nationalists bred relentless violence and the delusions of militant nationalisms, which is exactly what is happening now.

Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s ascendancy received vituperative opposition not just from royalist elements, but also from Ladakh’s Tibetan Buddhists who were apprehensive about the sudden rise of a new Kashmiri Muslim elite and were particularly fearful of the implications of its land reform policies for the Buddhist clergy’s enormous private land-holdings in Ladakh. As the elected head of government Abdullah “pushed through a set of major reforms, the most important of which was the “land to the tiller” legislation, which destroyed the power of the landlords, most of whom were non-Muslims. They were allowed to keep a maximum of 20 acres, provided they worked on the land themselves: 188,775 acres were transferred to 153,399 peasants, while the government organized collective farming on 90,000 acres. A law was passed prohibiting the sale of land to non-Kashmiris, thus preserving the basic topography of the region.”

The new economic plan of the state, formulated and executed by Abdullah’s government, underlined cooperative enterprise as opposed to malignant competition, in keeping with Abdullah’s socialist politics, which implied the organization and control of marketing and trade by the state. This revolutionary economic agenda in a hitherto feudal economy enabled the abolition of landlordism, allocation of land to the tiller, cooperative guilds of peasants, people’s control of forests, organized and planned cultivation of land, the development of sericulture, pisciculture and fruit orchards, and the utilization of forest and mineral wealth for the betterment of the populace. Tillers were assured of the right to work on the land without incurring the wrath of exploitative creditors, and were guaranteed material, social and health benefits (Korbel [1954] 2002: 204). These measures signaled the end of the chapter of peasant exploitation and subservience, and opened a new chapter of peasant emancipation.

Sheikh Abdullah’s unsurpassed achievement during his years as the prime minister of J & K from 1948 to 1953 was the abolition of the exploitative feudal system in the agrarian economy. He was also responsible for the eradication of monarchical rule. A.M. Diakov, a Soviet specialist on India, wrote about the progressive and democratic policies adopted by Abdullah’s National Conference (NC): “After the Second World War, a national movement in Kashmir developed the program of doing away with the Maharaja, of turning Kashmir into a democratic republic, of giving to the people of Kashmir the right of self-determination.”

The Dogra monarchy was formally abolished in 1952, and the last monarch’s heir apparent, Karan Singh, was declared the titular head of state. Disregarding the attempts of the Indian government to ratify its authority in J & K, the UN Security Council passed a resolution in March 1951 reminding the governments and authorities concerned of the premises of the Security Council resolutions of 21 April 1948, 3 June 1948 and 14 March 1950, and the United Nations (UN) Commission for India and Pakistan resolutions of 13 August 1948 and 5 January 1949, according to which a final decision about the status of the state would be made in accordance with the wishes of its people expressed in a free and fair referendum held under the impartial auspices of the UN.

This resolution also determined that the convening of a Constituent Assembly as recommended by the general council of the “All Jammu and Kashmir National Conference,” and any decision that the Assembly might take and attempt to execute determining the political affiliation of the entire state or any part thereof, would be considered as not in accordance with the above principles and would therefore be disregarded .

When Sheikh Abdullah first voiced his unrelenting opposition to autocratic rule in the state, his political stance was applauded by some sections of the Indian press, which, by foregrounding his position, further brought it out of the catacombs of provincialism: “It is imperialism’s game to disrupt the great democratic movement led by the NC. . . . There is no doubt that the NC would defeat these disruptive efforts by placing in the forefront the issue of ending the present autocratic regime and establishing a fully democratic government in accordance with its program.” (Communist, October 1947, quoted in Krishen 1951: 3–4)

Despite the injunction of the Security Council, Abdullah and his organization convened a Constituent Assembly in 1951. The NC regime was faced with unstinting opposition in the Hindu-dominated southern and southeastern districts of the Jammu region. Disgruntled elements comprising officials in the former maharaja’s administration who had been divested of their authority by the installation of a democratic regime in the state, and Hindu landlords stripped of their despotism by the NC administration’s populist land reforms, founded an organization called the Praja Parishad in late 1947, which was at loggerheads with Abdullah’s regime since 1949 (see Bose 1997: 104–64).

Despite all the odds, Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah sought to maintain Kashmir’s autonomous status. Tariq Ali makes an astute observation regarding Abdullah’s locus standi: If Sheikh Abdullah had allied himself with Pakistan, the Indian government and its troops would have been unpleasantly disarmed. But he considered the political and social ideologies of the Muslim League extremely conservative and was afraid that if Kashmir acceded to Pakistan, the Punjabi feudal lords who were at the helm of the ship of policy making in the Muslim League would hamper political and social progress. In order to prevent such an occurrence, Abdullah agreed to support the Indian military presence in the State provided under United Nations auspices in J & K.

The purportedly autonomous status of J & K under Abdullah’s government provoked the ire of the Hindu nationalist parties, which sought the unequivocal integration of the state into the Indian Union.

The unitary concept of nationalism that these organizations subscribed to challenged the basic principle that the nation was founded on, namely, democracy. In such a nationalist project, one of the forms that the nullification of past and present histories takes is the subjection of religious minorities to a centralized and authoritarian state buttressed by nostalgia of a “glorious past.”

The unequivocal aim of the supporters of the integration of J & K into the Indian Union was to expunge the political autonomy endowed on the state by India’s constitutional provisions.

According to the unitary discourse of sovereignty disseminated by the Hindu nationalists, J & K was not entitled to the signifiers of statehood – a prime minister, flag and constitution. The concept of nationalism constructed by Hindu nationalists bred relentless violence and the delusions of militant nationalisms, which is exactly what is happening now.

PALESTINA

One must note that the Israeli center-"left" party ( a merger of Meretz, Ehud Barak and Labor's Stav Shaffir) felt the need to be called the Zionist Union in the 2015 elections but has since become the Democratic Union... as if, finally, conceding that to be a leftist in Israel, you have to ultimately champion democracy, not Zionism. Which exposes the tension between Zionism and democracy and, seemingly, conceding that to be a leftist in Israel, you have to ultimately champion one over the other. This says a great deal about the current state of Israeli politics.

The neo-fascist exposed face of Israeli majority citizens shows that htere is no place in democracy for so called liberal Zionism. The idea that Israel can be a Jewish and democratic state with internationally recognized borders, which both acknowledges its national Palestinian minority and reaches an agreement to establish a Palestinian state, has absorbed a fatal blow years ago. Israelis have consistently voted against this idea; it is now impossible to see how it could ever be realized without foreign intervention and U.N. boots on the ground.

Great Britain in general and Winston Churchill in particular had it all wrong.

Great Britain in general and Winston Churchill in particular had it all wrong.

Israel voted for occupation, no matter who prevails

BRASIL