Trump's efforts to install a far right opposition will only incite violence and further destabilize the region.

We must support Mexico, Uruguay and the Vatican's efforts to facilitate a peaceful dialogue.

Whether you and I like Maduro or not.

Like the 17 year-old student Naikary Agresot said: “I want a change – but not through a coup or an intervention. I wish Maduro could understand that things have gotten out of control and make room for someone who truly can change the country.”

Change for better, yes, preserving Venezuela's oïl and its sovereignity.

Venezuela does not need another charismatic strongman

A campanha de desestabilização e os esforços econômico-militares de Trump para instalar em Caracas uma oposição de extrema-direita do modelo do neofascista brasileiro Jair Bolsonaro apenas incitará a violência e deteriorará o já esfrangalhado sistema político-social e econômico dos nossos vizinhos e da nossa região.

Temos de apoiar os esforços do México, do Uruguai e do Vaticano no sentido de facilitar um diálogo pacífico.

Isto não significa apoiar Maduro e sim dar uma chance aos venezuelanos de encontrar seu próprio caminho, democraticamente, sem pressão do Planalto e sem intervenção estadunidense. Mais 5.000 GIs foram enviados para a a Colômbia.

Não é porque Jair Bozonaro - Tropical Trump, como é chamado na Europa - está sucateando o Brasil e entregando nosso país de mãos beijadas aos gringos que os venezuelanos também têm de perder seu petróleo e virar vassalos dos Estados Unidos.

Chris Hedges, one of the best international journalists of our time, gives a sermon (19'47)

Journalists can help people by telling the truth, or by as much truth as they can find, and acting not as agents of governments, of power, but of people.

That is real journalism.

The rest is specious and false.

When I began as an international journalist, especially as a foreign correspondent, the press in the UK was conservative and owned by powerful establishment forces, as it is now. But the difference compared to today is that there were spaces for independent journalism that dissented from the received wisdom of authority. That space has now all but closed and independent journalists have gone to the internet, or to a metaphoric underground.

The single biggest challenge of journalism is rescuing journalists from their deferential role as the stenographer of great power. The United States has constitutionally the freest press on earth, yet in practice it has a media obsequious to the formulas and deceptions of power. That is why the US was effectively given media approval to invade Iraq, and Libya, and Syria and dozens of other countries.

WikiLeaks is possibly the most exciting development in journalism in my lifetime. As an investigative journalist, I have often had to rely on the courageous, principled acts of whistle-blowers. The truth about the Vietnam War was told when Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers. The truth about Iraq and Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia and many other flashpoints was told when WikiLeaks published the revelations of whistle-blowers.

When you consider that 100 percent of WikiLeaks leaks are authentic and accurate, you can understand the impact, as well as the fury generated among secretive powerful forces. Julian Assange is a political refugee in London for one reason only: WikiLeaks told the truth about the greatest crimes of the 21st century. He is not forgiven for that, and he should be supported by journalists and by people everywhere."

I totally agree with John Pilger, one of the few (as Chris Hedges) always trustworthy journalists alive.

Fortaleça o jornalismo independente no Brasil.

Ajude a construir um fundo coletivo para financiar projetos jornalísticos.

Apoie a diversidade no debate público nacional.

Empire Files: Trump is expanding the US empire - I (16'44)

That is real journalism.

The rest is specious and false.

When I began as an international journalist, especially as a foreign correspondent, the press in the UK was conservative and owned by powerful establishment forces, as it is now. But the difference compared to today is that there were spaces for independent journalism that dissented from the received wisdom of authority. That space has now all but closed and independent journalists have gone to the internet, or to a metaphoric underground.

The single biggest challenge of journalism is rescuing journalists from their deferential role as the stenographer of great power. The United States has constitutionally the freest press on earth, yet in practice it has a media obsequious to the formulas and deceptions of power. That is why the US was effectively given media approval to invade Iraq, and Libya, and Syria and dozens of other countries.

WikiLeaks is possibly the most exciting development in journalism in my lifetime. As an investigative journalist, I have often had to rely on the courageous, principled acts of whistle-blowers. The truth about the Vietnam War was told when Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers. The truth about Iraq and Afghanistan, and Saudi Arabia and many other flashpoints was told when WikiLeaks published the revelations of whistle-blowers.

When you consider that 100 percent of WikiLeaks leaks are authentic and accurate, you can understand the impact, as well as the fury generated among secretive powerful forces. Julian Assange is a political refugee in London for one reason only: WikiLeaks told the truth about the greatest crimes of the 21st century. He is not forgiven for that, and he should be supported by journalists and by people everywhere."

I totally agree with John Pilger, one of the few (as Chris Hedges) always trustworthy journalists alive.

Fortaleça o jornalismo independente no Brasil.

Ajude a construir um fundo coletivo para financiar projetos jornalísticos.

Apoie a diversidade no debate público nacional.

Empire Files: Trump is expanding the US empire - I (16'44)

No self-respecting journalist forgets the effect of pictures of columns of Syrian refugees, far away from UK in central Europe, had on the British Brexit referendum in 2016.

Three days after the little inflatable boat beached at Dungeness, the US secretary of state Mike Pompeo made a speech in Cairo outlining the Trump Middle East policy, which inadvertently goes a long way to explain how the dinghy got there. After criticising former president Obama for being insufficiently belligerent, Pompeo promised that the US would “use diplomacy and work with our partners to expel every last Iranian boot” from Syria; and that sanctions on Iran – and presumably Syria – will be rigorously imposed.

Just how this is to be done is less clear, but Pompeo insisted that the US will wage military and economic war in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Syria, which inevitably means that normal life will be impossible in all of these places.

Though the US and its allies are unlikely to win any victories against Iran or Bashar al-Assad, the US can keep a permanent crisis simmering across a swathe of countries between the Pakistan border and the Mediterranean, thereby ensuring in the long term that a portion of the 170 million people living in this vast area will become so desperate that they will take every risk and spend the last of their money to flee to Western Europe. Keep in mind that these crises tend to cross-infect each other, so instability in Syria means instability in Iraq.

Given the seismic impact of migration fuelled by war or sanctions in the Middle East and North Africa on the politics of Europe over the last seven or eight years, it shows a high degree of self-destructive foolishness on the part of European governments not to have done more to restore peace. They have got away with it because voters have failed to see the linkage between foreign intervention and the consequent waves of immigrants from their ruined countries.

Yet the connection should be easy enough to grasp: in 2011, the Nato powers led by UK and France backed an insurgency in Libya that overthrew and killed Gaddafi. Libya was reduced to violent chaos presided over by criminalised militias, which opened the door to migrants from North and West Africa transiting Libya and drowning as they try to cross the Mediterranean.

In Syria, the US and UK long ago decided that they would be unable to get rid of Assad – indeed they did not really want to since they believed he would be replaced by al-Qaeda or Isis. But American, British and French policy makers were happy to keep the conflict bubbling to prevent Assad, Russia and Iran winning a complete victory. A result of prolonging the conflict is that the chance of the 6.5 million Syrian refugees ever returning home grows less by the year.

The economic devastation inflicted by these long wars is often underestimated because it is less visible and melodramatic than the ruins of Raqqa, Aleppo, Homs and Mosul. I was driving in northeast Syria last year, west of the Euphrates, through land that was once some of the most productive in the country, producing grain and cotton. But the irrigation canals were empty and for mile after mile the land has reverted to rough pasture. Our car kept stopping because the road was blocked by herds of sheep being driven by shepherds to crop the scanty grass as the area reverts to semi-desert because there is no electric power to pump water from the Euphrates.

European governments try to distinguish between refugees seeking safety because of military action or because of economic hardship; yet they increasingly go together. Syria and Iran are both being subjected to tight economic sieges. But the casualties of sanctions – as was brutally demonstrated by the 13-year-long UN sanctions on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq between 1990 and 2003 – are not the members of the regime but the civilian population. Mass flight becomes an unavoidable option.

Iraq never truly recovered from a period of sanctions during which its administrative, education and health systems were shattered and its best-educated people fled the country. The first casualties of sanctions are always on the margins and never those in power, who are the supposed target. An example of this was the re-imposition of US sanctions on Iran in 2018, which led to the exodus of 440,000 low paid Afghan workers who are not going to get jobs back in Afghanistan (where unemployment is 40 per cent) and who in many cases will therefore try to get to Europe.

Wars that are not concluded trigger waves of migrants even when there is no fighting because all sides need to recruit more soldiers from an unwilling population. In Syria, families are terrified of their sons of military age being conscripted not only by the Syrian army but by the Kurdish YPG military forces or al-Qaeda type militias.

There is a clear connection between western intervention in the Middle East and North Africa and the arrival of boat people on the beaches of southeast England. But much of the media does not highlight this and, by and large, voters do not seem to notice it.

British David Cameron and French Nicolas Sarkozy never suffered political damage from their ill-advised role in destroying the Libyan state. A couple of years later Cameron was pressing for Britain to join the US in air attacks on Syria, which would certainly not have got rid of Assad without a prolonged air campaign similar to those in Iraq and Libya.

The outcome of these interventions is not just the outflow of refugees from zones of conflict: the weakening or destruction of states in the region enables groups like al-Qaeda and Isis to find secure base areas where they can regroup their forces. A fragmented Syria is ideal for such purposes because the jihadis can dodge between rival powers. Pompeo’s bombast will be a welcome development for them.

The only solution in northeast Syria is for the US to withdraw militarily under an agreement whereby Turkey does not invade Syria, in return for the Syrian government backed by Russia absorbing the Kurdish quasi-state so hated by the Turks and giving it some degree of internationally guaranteed autonomy. Any other option is likely to provoke a Turkish invasion and two million Kurds in flight – a very few of whom will one day end up on the pebble beaches of Dungeness.

Intervention produces devastation and gives rise to anger and violence. In "reaction", comes the "war on terror".

By any reasonable estimate, the monetary and human costs of the U.S.-led war on terrorism has been considerable. To the political scientists at Brown University, the numbers have been astronomical. The Ivy League university’s Cost of War Project calculates that Washington will spend approximately $5.9 trillion between FY2001-FY2019, a pot of money that includes over $2 trillion in overseas contingency operations, $924 billion in homeland security spending, and $353 billion in medical and disability care for U.S. troops serving in overseas conflict zones. Add the cost of interest to borrowed money into the equation, and the American people will be paying back the debt for decades to come.

The never-ending war on terrorism, of course, has also twisted the U.S. Armed Forces into a pretzel. With the United States operating in 40 percent of the world’s countries and leading sixty-five separate security training programs from the jungles of Columbia to the jungles of Thailand, is it any wonder why defense-minded think tanks, the Pentagon leadership and the armed services committees continue to talk about a readiness crisis? Washington is deploying troops, trainers and advisers to so many places that even America’s elected representatives are frequently in the dark about how the military is being used, what it is doing and where it is operating. Indeed, when four U.S. special forces troops were ambushed and killed by a small group of Islamic State-affiliated tribal fighters during a joint U.S. raid near the Niger-Mali border, lawmakers in Washington were aghast that American soldiers were in Niger to begin with. In a televised admission about how out-of-the-loop lawmakers were, Sen. Lindsey Graham commented that “[w]e don't know exactly where we're at in the world, militarily, and what we're doing.”

Presumably, all of this expenditure of monetary and military resources should buy Americans at least a decent level of security. The high investment would be worth it if the United States was any safer from terrorism. Yet the opposite would appear to be the case. An October 2017 Charles Koch Institute/RealClearDefense survey found that a plurality of Americans (43 percent) and veterans (41 percent) believe U.S. foreign policy over the last twenty years has actually made the country less safe—a result not exactly conducive to what U.S. policymakers are looking for.

The American people aren’t crazy for feeling the way they do. There is hard data supporting their concern. Taking a comprehensive look at the terrorism problem over many decades, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Transnational Threats Project discovered that the number of Salafi-jihadist fighters has increased by 270 percent since 2001. In 2018, there were sixty-seven jihadist groups operating around the world, a 180 percent increase since 2001. The number of fighters could be as high as 280,000, the highest in forty years. And in a disturbing sense of irony, many of those fighters reside in countries (Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya) the United States has invaded and/or bombed over the last seventeen years.

All of this begs the question: is Washington’s counterterrorism strategy having the desired effect of enhancing the security of Americans? Or is the strategy simply creating more terrorists than it is killing, throwing more taxpayer money down the toilet, and further straining the U.S. military’s limited resources?

We won’t know the answer until President Donald Trump orders his administration to conduct an honest, impartial, whole-of-government appraisal of the current policy. When he does, perhaps Trump will be more likely to overrule his conventional national security advisers who continue to argue for an unconditional and timeless American military commitment in Syria and Afghanistan.

These last days, the economic and political powerful people gathered in Switzerland, in Davos, talking nonsense.

At the same time as Davos, Oxfam releases a report on world poverty and inequality. In 2016, their report said: "The richest 1 percent now have more wealth than the rest of the world combined."

Uh-oh! It looked like things were getting out of hand. Surely all those smart, caring, thoughtful people - with power and the means to change things - sat down at their mega-gathering - strategised and acted!

No. It got worse.

"Eighty-two percent of the wealth generated [in 2017] went to the richest one percent of the global population."

In 2018, "the wealth of the world's billionaires increased ... $2.5 billion a day."

There are 2,202 billionaires, so if that were divided equally among them, they would each be gaining $1,132,246 every day of last year.

One of the many arguments against restraining or limiting or taxing the ultra-rich is that it is not a "zero-sum game," it is not a static pie where a bigger slice for them means a smaller slice for you! Stop whining. However, "the poorest half of humanity saw their wealth dwindle by 11 percent, billionaires' riches increased by 12 percent." So it sure looks like the greedy guys are getting fatter by eating away at the slices of the hungry people.

Many of the people that gather in Davos once a year must be aware, to some degree, that inequality is a problem. That it is creating instability. That it underlies and aggravates conflicts. Some may even accept that it leads to dangerous economic instability, like the crash of 2008 and the worldwide Great Recession.

The equation is quite direct. Money buys power. Power is used to increase wealth. Which buys more power. The solutions, the only real solutions, are very clear. Decrease the money the ultra-rich have and increase the amount of money that everyone else has. That translates into higher taxes, fewer tax dodges and enforcement against tax havens. Also, backing unions so that working people have more power and tackling the more complex problem of influence of money in politics.

These are not being advocated in Davos.

Let us not fool ourselves. Indeed, there is a show of do-gooder - let's save art, education and frogs lectures and humanitarian conférences. But they are there for show. Who goes to Davos to listen to that stuff? People go to meet others with money and power. To connect. Do deals. To protect what they've got and get some more. The NGOs are invited to cover up the happy few's economical schemes against social welfare.

Em 2019, a Semana Anual do Apartheid israelense acontecerá do dia 18 de março a 8 de abril no mundo inteiro.

Ative um comitê em sua cidade, escola, universidade.

Para organizar as manifestações político-culturais, entre em contato com o BDS Brasil (https://bdsmovement.net/pt) ou acesse diretamente o link internacional apartheidweek.org e organize as atividades de solidariedade com o povo palestino há 71 anos ocupado.

O tema deste ano é "Parem de armar o Colonialismo".

E não se esqueça de checar a origem dos produtos que consome para boicotar Israel, inclusive Hewlett Packard.

The 15th Annual Israeli Apartheid Week of actions will take place all around the world between March 18th and April 8th 2019 under the theme “Stop Arming Colonialism”.

Israeli Apartheid Week (IAW) is an international series of events that seeks to raise awareness about Israel’s apartheid regime over the Palestinian people and build support for the growing Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. It now takes place in over 200 cities across the world, where events such as lectures, film screenings, direct action, cultural performances, postering, among many more help in grassroots organizing for effective solidarity with the Palestinian liberation struggle.

Israel is able to maintain its illegal occupation and apartheid regime over Palestinians partly due to its arms sales and the military support it receives from governments across the world. The United States alone is the single largest supplier of arms and military aid to Israel, followed by European states. These directly sustain Israel’s oppression and human rights violations.

In the Global South, Israel has been known to supply weapons to genocidal regimes in Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and elsewhere. Presently, Israel is a major arms exporter to right-wing, authoritarian regimes from Brazil to India, the Philippines and beyond. These weapons are promoted as ‘field-tested’, which means they have been used to kill or injure Palestinians. In fact, Israel is already promoting the technology it has used to repress the Great March of Return in Gaza calling for the right of refugees to return home and an end to the siege. These arms deals finance Israel’s apartheid regime and its illegal occupation while simultaneously deepening militarization and persecution of people’s movements and oppressed communities in countries where they are bought.

The Palestinian-led BDS movement has reiterated the demand for a military embargo on Israel in the light of Israel’s violent repression of the Great March of Return. International human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have also responded to the Israeli massacre in Gaza with this demand. The UK Labour Party, in its conference in September 2018, passed a motion condemning Israel’s killing of Palestinian protesters in Gaza and called for a freeze of arms sales to Israel.

Ending arms trade, military aid and cooperation with Israel will undercut financial and military support for its regime of apartheid, settler-colonialism and illegal occupation. It will also end the flow of Israeli weapons and security technology and techniques to governments that suppress resistance of their own citizens, people’s movements and communities against policies that deprive them of fundamental rights, including the right to the natural resources of their country.

A military embargo on Israel is a measure for freedom and justice of Palestinians and oppressed peoples in many parts of the world. It can successfully be achieved with massive grassroots efforts, similar to the sustained global mobilization that eventually compelled the United Nations to impose a binding international military embargo against South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Israeli Apartheid Week 2019 will be an important platform for building the campaign for a military embargo on Israel. We invite progressive groups to organize events on their campuses and in their cities to popularize and build momentum in this direction.

If you would like to organize and be part of Israeli Apartheid Week 2019 on your campus or in your city, check out what events are already planned at apartheidweek.org, find us on Facebook and Twitter, register onlinehttp://apartheidweek.org/organise/ and get in touch with IAW coordinators in your region.

Three days after the little inflatable boat beached at Dungeness, the US secretary of state Mike Pompeo made a speech in Cairo outlining the Trump Middle East policy, which inadvertently goes a long way to explain how the dinghy got there. After criticising former president Obama for being insufficiently belligerent, Pompeo promised that the US would “use diplomacy and work with our partners to expel every last Iranian boot” from Syria; and that sanctions on Iran – and presumably Syria – will be rigorously imposed.

Just how this is to be done is less clear, but Pompeo insisted that the US will wage military and economic war in Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Syria, which inevitably means that normal life will be impossible in all of these places.

Though the US and its allies are unlikely to win any victories against Iran or Bashar al-Assad, the US can keep a permanent crisis simmering across a swathe of countries between the Pakistan border and the Mediterranean, thereby ensuring in the long term that a portion of the 170 million people living in this vast area will become so desperate that they will take every risk and spend the last of their money to flee to Western Europe. Keep in mind that these crises tend to cross-infect each other, so instability in Syria means instability in Iraq.

Given the seismic impact of migration fuelled by war or sanctions in the Middle East and North Africa on the politics of Europe over the last seven or eight years, it shows a high degree of self-destructive foolishness on the part of European governments not to have done more to restore peace. They have got away with it because voters have failed to see the linkage between foreign intervention and the consequent waves of immigrants from their ruined countries.

Yet the connection should be easy enough to grasp: in 2011, the Nato powers led by UK and France backed an insurgency in Libya that overthrew and killed Gaddafi. Libya was reduced to violent chaos presided over by criminalised militias, which opened the door to migrants from North and West Africa transiting Libya and drowning as they try to cross the Mediterranean.

In Syria, the US and UK long ago decided that they would be unable to get rid of Assad – indeed they did not really want to since they believed he would be replaced by al-Qaeda or Isis. But American, British and French policy makers were happy to keep the conflict bubbling to prevent Assad, Russia and Iran winning a complete victory. A result of prolonging the conflict is that the chance of the 6.5 million Syrian refugees ever returning home grows less by the year.

The economic devastation inflicted by these long wars is often underestimated because it is less visible and melodramatic than the ruins of Raqqa, Aleppo, Homs and Mosul. I was driving in northeast Syria last year, west of the Euphrates, through land that was once some of the most productive in the country, producing grain and cotton. But the irrigation canals were empty and for mile after mile the land has reverted to rough pasture. Our car kept stopping because the road was blocked by herds of sheep being driven by shepherds to crop the scanty grass as the area reverts to semi-desert because there is no electric power to pump water from the Euphrates.

European governments try to distinguish between refugees seeking safety because of military action or because of economic hardship; yet they increasingly go together. Syria and Iran are both being subjected to tight economic sieges. But the casualties of sanctions – as was brutally demonstrated by the 13-year-long UN sanctions on Saddam Hussein’s Iraq between 1990 and 2003 – are not the members of the regime but the civilian population. Mass flight becomes an unavoidable option.

Iraq never truly recovered from a period of sanctions during which its administrative, education and health systems were shattered and its best-educated people fled the country. The first casualties of sanctions are always on the margins and never those in power, who are the supposed target. An example of this was the re-imposition of US sanctions on Iran in 2018, which led to the exodus of 440,000 low paid Afghan workers who are not going to get jobs back in Afghanistan (where unemployment is 40 per cent) and who in many cases will therefore try to get to Europe.

Wars that are not concluded trigger waves of migrants even when there is no fighting because all sides need to recruit more soldiers from an unwilling population. In Syria, families are terrified of their sons of military age being conscripted not only by the Syrian army but by the Kurdish YPG military forces or al-Qaeda type militias.

There is a clear connection between western intervention in the Middle East and North Africa and the arrival of boat people on the beaches of southeast England. But much of the media does not highlight this and, by and large, voters do not seem to notice it.

British David Cameron and French Nicolas Sarkozy never suffered political damage from their ill-advised role in destroying the Libyan state. A couple of years later Cameron was pressing for Britain to join the US in air attacks on Syria, which would certainly not have got rid of Assad without a prolonged air campaign similar to those in Iraq and Libya.

The outcome of these interventions is not just the outflow of refugees from zones of conflict: the weakening or destruction of states in the region enables groups like al-Qaeda and Isis to find secure base areas where they can regroup their forces. A fragmented Syria is ideal for such purposes because the jihadis can dodge between rival powers. Pompeo’s bombast will be a welcome development for them.

The only solution in northeast Syria is for the US to withdraw militarily under an agreement whereby Turkey does not invade Syria, in return for the Syrian government backed by Russia absorbing the Kurdish quasi-state so hated by the Turks and giving it some degree of internationally guaranteed autonomy. Any other option is likely to provoke a Turkish invasion and two million Kurds in flight – a very few of whom will one day end up on the pebble beaches of Dungeness.

Intervention produces devastation and gives rise to anger and violence. In "reaction", comes the "war on terror".

By any reasonable estimate, the monetary and human costs of the U.S.-led war on terrorism has been considerable. To the political scientists at Brown University, the numbers have been astronomical. The Ivy League university’s Cost of War Project calculates that Washington will spend approximately $5.9 trillion between FY2001-FY2019, a pot of money that includes over $2 trillion in overseas contingency operations, $924 billion in homeland security spending, and $353 billion in medical and disability care for U.S. troops serving in overseas conflict zones. Add the cost of interest to borrowed money into the equation, and the American people will be paying back the debt for decades to come.

The never-ending war on terrorism, of course, has also twisted the U.S. Armed Forces into a pretzel. With the United States operating in 40 percent of the world’s countries and leading sixty-five separate security training programs from the jungles of Columbia to the jungles of Thailand, is it any wonder why defense-minded think tanks, the Pentagon leadership and the armed services committees continue to talk about a readiness crisis? Washington is deploying troops, trainers and advisers to so many places that even America’s elected representatives are frequently in the dark about how the military is being used, what it is doing and where it is operating. Indeed, when four U.S. special forces troops were ambushed and killed by a small group of Islamic State-affiliated tribal fighters during a joint U.S. raid near the Niger-Mali border, lawmakers in Washington were aghast that American soldiers were in Niger to begin with. In a televised admission about how out-of-the-loop lawmakers were, Sen. Lindsey Graham commented that “[w]e don't know exactly where we're at in the world, militarily, and what we're doing.”

Presumably, all of this expenditure of monetary and military resources should buy Americans at least a decent level of security. The high investment would be worth it if the United States was any safer from terrorism. Yet the opposite would appear to be the case. An October 2017 Charles Koch Institute/RealClearDefense survey found that a plurality of Americans (43 percent) and veterans (41 percent) believe U.S. foreign policy over the last twenty years has actually made the country less safe—a result not exactly conducive to what U.S. policymakers are looking for.

The American people aren’t crazy for feeling the way they do. There is hard data supporting their concern. Taking a comprehensive look at the terrorism problem over many decades, the Center for Strategic and International Studies’ Transnational Threats Project discovered that the number of Salafi-jihadist fighters has increased by 270 percent since 2001. In 2018, there were sixty-seven jihadist groups operating around the world, a 180 percent increase since 2001. The number of fighters could be as high as 280,000, the highest in forty years. And in a disturbing sense of irony, many of those fighters reside in countries (Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya) the United States has invaded and/or bombed over the last seventeen years.

All of this begs the question: is Washington’s counterterrorism strategy having the desired effect of enhancing the security of Americans? Or is the strategy simply creating more terrorists than it is killing, throwing more taxpayer money down the toilet, and further straining the U.S. military’s limited resources?

We won’t know the answer until President Donald Trump orders his administration to conduct an honest, impartial, whole-of-government appraisal of the current policy. When he does, perhaps Trump will be more likely to overrule his conventional national security advisers who continue to argue for an unconditional and timeless American military commitment in Syria and Afghanistan.

These last days, the economic and political powerful people gathered in Switzerland, in Davos, talking nonsense.

At the same time as Davos, Oxfam releases a report on world poverty and inequality. In 2016, their report said: "The richest 1 percent now have more wealth than the rest of the world combined."

Uh-oh! It looked like things were getting out of hand. Surely all those smart, caring, thoughtful people - with power and the means to change things - sat down at their mega-gathering - strategised and acted!

No. It got worse.

"Eighty-two percent of the wealth generated [in 2017] went to the richest one percent of the global population."

In 2018, "the wealth of the world's billionaires increased ... $2.5 billion a day."

There are 2,202 billionaires, so if that were divided equally among them, they would each be gaining $1,132,246 every day of last year.

One of the many arguments against restraining or limiting or taxing the ultra-rich is that it is not a "zero-sum game," it is not a static pie where a bigger slice for them means a smaller slice for you! Stop whining. However, "the poorest half of humanity saw their wealth dwindle by 11 percent, billionaires' riches increased by 12 percent." So it sure looks like the greedy guys are getting fatter by eating away at the slices of the hungry people.

The equation is quite direct. Money buys power. Power is used to increase wealth. Which buys more power. The solutions, the only real solutions, are very clear. Decrease the money the ultra-rich have and increase the amount of money that everyone else has. That translates into higher taxes, fewer tax dodges and enforcement against tax havens. Also, backing unions so that working people have more power and tackling the more complex problem of influence of money in politics.

These are not being advocated in Davos.

Let us not fool ourselves. Indeed, there is a show of do-gooder - let's save art, education and frogs lectures and humanitarian conférences. But they are there for show. Who goes to Davos to listen to that stuff? People go to meet others with money and power. To connect. Do deals. To protect what they've got and get some more. The NGOs are invited to cover up the happy few's economical schemes against social welfare.

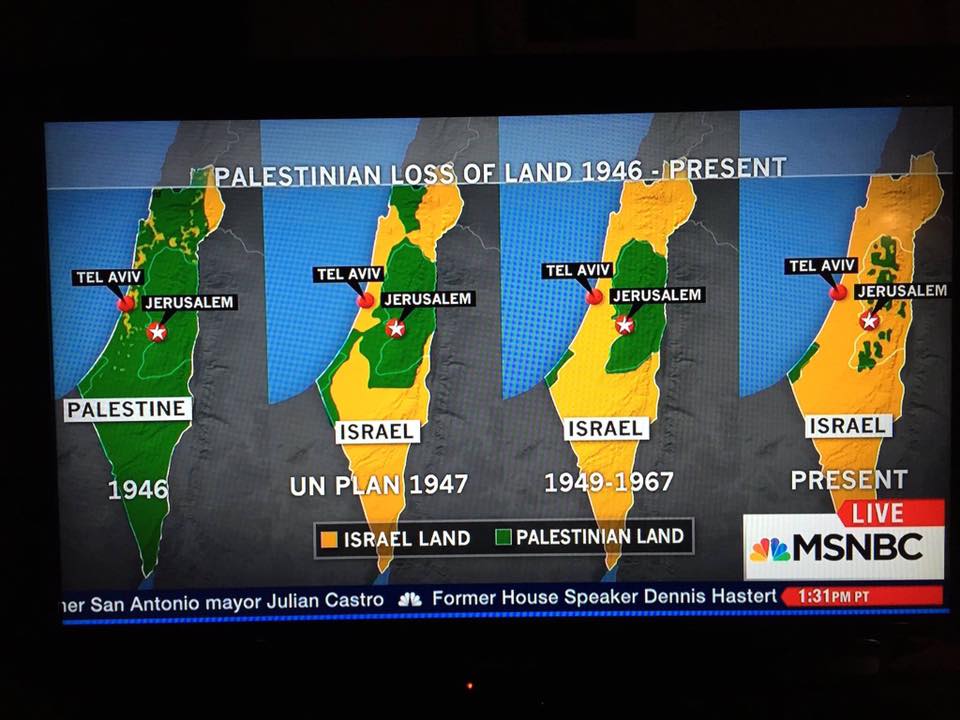

PALESTINA

Daily Life Occupation

Daily Life Occupation

Ative um comitê em sua cidade, escola, universidade.

Para organizar as manifestações político-culturais, entre em contato com o BDS Brasil (https://bdsmovement.net/pt) ou acesse diretamente o link internacional apartheidweek.org e organize as atividades de solidariedade com o povo palestino há 71 anos ocupado.

O tema deste ano é "Parem de armar o Colonialismo".

E não se esqueça de checar a origem dos produtos que consome para boicotar Israel, inclusive Hewlett Packard.

The 15th Annual Israeli Apartheid Week of actions will take place all around the world between March 18th and April 8th 2019 under the theme “Stop Arming Colonialism”.

Israeli Apartheid Week (IAW) is an international series of events that seeks to raise awareness about Israel’s apartheid regime over the Palestinian people and build support for the growing Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. It now takes place in over 200 cities across the world, where events such as lectures, film screenings, direct action, cultural performances, postering, among many more help in grassroots organizing for effective solidarity with the Palestinian liberation struggle.

Israel is able to maintain its illegal occupation and apartheid regime over Palestinians partly due to its arms sales and the military support it receives from governments across the world. The United States alone is the single largest supplier of arms and military aid to Israel, followed by European states. These directly sustain Israel’s oppression and human rights violations.

In the Global South, Israel has been known to supply weapons to genocidal regimes in Rwanda, Sri Lanka, Myanmar and elsewhere. Presently, Israel is a major arms exporter to right-wing, authoritarian regimes from Brazil to India, the Philippines and beyond. These weapons are promoted as ‘field-tested’, which means they have been used to kill or injure Palestinians. In fact, Israel is already promoting the technology it has used to repress the Great March of Return in Gaza calling for the right of refugees to return home and an end to the siege. These arms deals finance Israel’s apartheid regime and its illegal occupation while simultaneously deepening militarization and persecution of people’s movements and oppressed communities in countries where they are bought.

The Palestinian-led BDS movement has reiterated the demand for a military embargo on Israel in the light of Israel’s violent repression of the Great March of Return. International human rights organizations such as Amnesty International have also responded to the Israeli massacre in Gaza with this demand. The UK Labour Party, in its conference in September 2018, passed a motion condemning Israel’s killing of Palestinian protesters in Gaza and called for a freeze of arms sales to Israel.

Ending arms trade, military aid and cooperation with Israel will undercut financial and military support for its regime of apartheid, settler-colonialism and illegal occupation. It will also end the flow of Israeli weapons and security technology and techniques to governments that suppress resistance of their own citizens, people’s movements and communities against policies that deprive them of fundamental rights, including the right to the natural resources of their country.

A military embargo on Israel is a measure for freedom and justice of Palestinians and oppressed peoples in many parts of the world. It can successfully be achieved with massive grassroots efforts, similar to the sustained global mobilization that eventually compelled the United Nations to impose a binding international military embargo against South Africa’s apartheid regime.

Israeli Apartheid Week 2019 will be an important platform for building the campaign for a military embargo on Israel. We invite progressive groups to organize events on their campuses and in their cities to popularize and build momentum in this direction.

If you would like to organize and be part of Israeli Apartheid Week 2019 on your campus or in your city, check out what events are already planned at apartheidweek.org, find us on Facebook and Twitter, register onlinehttp://apartheidweek.org/organise/ and get in touch with IAW coordinators in your region.

For more information and support, please contact iawinfo@apartheidweek.org.